A (different) perspective on statins in the primary prevention of heart disease

Statins are the most studied drugs in all of medicine. Hundreds of thousands of patients have been randomized in statin trials. Yet many disagree on their role in preventing heart disease

Dear Readers, I publish the following opinion piece regarding the use of statin drugs in low-risk individuals without heart disease even though I disagree with most of the authors’ arguments. Since this is a rebuttal to an editorial I wrote, it would be helpful to first read the linked article in the lead sentence.

I do like the authors’ conclusions. And would re-iterate that the prevention of heart disease involves many actions—not just taking a medicine.

Purists may not like this article. Some may find it “dangerous” because it discourages the use of statin drugs for primary prevention. Sorry. Sensible Medicine remains a place where non-establishment opinions can be published. JMM

By Maryanne Demasi, PhD1 and Robert DuBroff, MD2

1 Investigative journalist, medical researcher, Australia

2 Cardiologist, Retired Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of New Mexico

Recently, John Mandrola, a respected cardiologist in Louisville, KY, published an article on why he has changed his mind about preventing heart disease in young people at low cardiac risk.

Whereas he previously thought that early medical intervention had little benefit, Dr Mandrola now argues that “younger lower-risk patients may have the most to gain from primary prevention,” and uses statin drugs that lower cholesterol, as an example of why his thinking has changed.

The use of statins in primary prevention has been hotly contested, with many concerned that the benefits do not outweigh the harms in people at low risk of heart disease. So, in the spirit of respectful and open debate, we present arguments for why we think statins in primary prevention are unlikely to benefit.

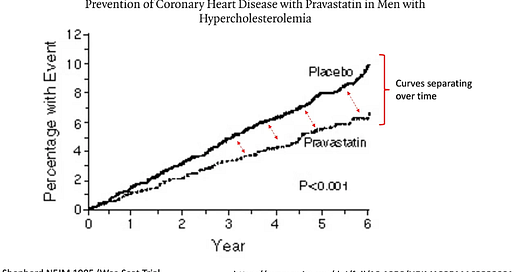

Dr Mandrola points out that the beneficial effect of statins increase over time. He cites a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that shows the effects of reducing cardiovascular events gets larger over time.

However, to infer that longer term treatment would confer a greater benefit ignores the fact that longer term treatment also confers a greater risk of complications. A perfect example of this is statin-associated diabetes.

The JUPITER trial analyzed people with normal cholesterol levels at low risk of heart disease and found a significant increase in new onset diabetes after a median of 1.9 years, later prompting the FDA to issue a safety label change for the entire class of statin drugs.

Observational studies of long-term statin exposure suggest that the relative risk of developing diabetes mellitus could range from 46% after 5.9 years (absolute risk 5.4%) to as high as 363% after 15-20 years (absolute risk 30/1000 patient-years) of statin exposure.

Consider also that many statin users will ignore more important lifestyle changes under the mistaken belief that they are ‘protected,’ a behavior referred to as statin gluttony.

Furthermore, based upon electronic medical records, statin discontinuation rates range from 25-50% within six months to one year after initiation. In the USAGE survey, the primary reason for discontinuation was side effects (62%).

An analysis published in BMJ Open found that among primary prevention statin trials of 3.5-6 years duration, taking a daily statin only postponed death by a median of 3.2 days. Can we truly endorse a long-term therapy that might prolong life by a few days while ignoring the substantial long-term harms?

In his article, Dr Mandrola says that “numerous trials have shown that statins consistently reduce the risk of first cardiac events by about 20-25% in relative terms,” but a full accounting of statin trials finds that the benefits in primary prevention are inconsistent and modest, at best.

Our study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, analyzed 21 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of statin drugs and found that taking a statin for an average of 4.4 years, showed a relative reduction in heart attacks of 29%, but in absolute terms, the reduction in risk was only 1.3% - which means the vast majority of people in the trial do not benefit over that period.

Moreover, another analysis of 16 statin RCTs (both primary and secondary prevention) published after government mandated regulations for the conduct of RCTs were instituted, found that none reported a mortality benefit and roughly two thirds found no cardiovascular benefit at all.

Dr Mandrola cites a 2023 imaging study that assessed blood vessel atherosclerosis over 6 years in nearly 3500 volunteers. It showed that it was the youngest people who had the highest odds of progression from elevated cholesterol.

At first glance, this observation suggests that younger patients might derive the greatest benefit. However, we should be cautious about extrapolating these results into a rationale for treating younger patients.

Treating a surrogate marker (like LDL-cholesterol) with statins doesn’t necessarily lead to a clinical benefit. Consider that no mortality or cardiovascular benefit was reported in a number of large, statin primary prevention trials (St Francis Heart, ALLHAT-LLT, AURORA, ASPEN, EMPATHY, GISSI-HF, SEAS).

Notably, the St Francis Heart study enrolled relatively young (average age 59) asymptomatic individuals with extremely high coronary calcium scores (>80th percentile).

Finally, Dr Mandrola points to a “Mendelian Randomization” study that compares individuals who were “naturally randomized” according to whether they had a genetically high cholesterol, or not. Those with the highest long-term exposure to high cholesterol because of their genetics, also had a higher risk of heart disease. This type of study, however, has an inherent, fatal flaw.

Mendelian Randomization studies ignore the entire clinical history of participants from the time they were born to when they were recruited into the study (as adults). So only survivors of the genetic mutation are analyzed, while those who may have died, experienced morbid events or had not been enrolled in the trial are ignored. Hence, we need to recognize the limitations of Mendelian Randomization studies before relying upon their conclusions to justify clinical decisions.

There are many studies that have not been included in Dr Mandrola’s article that might challenge his conclusions.

For example, our systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 RCTs found no consistent relationship between lowering LDL-Cholesterol with statins and the risk of death, heart attack or stroke. Also, widespread use of statins in Europe has not been associated with any reduction in cardiovascular disease mortality. And how do we reconcile the observation that heart related deaths in the US seem to be rising despite falling cholesterol levels?

There is an onus on physicians and scientists to change their opinions when the medical evidence changes, and we commend Dr Mandrola for taking the time to reassess his opinion on the primary prevention of heart disease.

For us, however, each study cited in Dr Mandrola’s article, in combination or on its own, has not persuaded us that the benefits of lowering cholesterol with statins in younger, primary prevention individuals, outweighs the harms.

In conclusion, we agree with Dr Mandrola, that “younger lower-risk patients may have the most to gain from primary prevention”, but primary prevention of heart disease begins with less emphasis on cholesterol-lowering statins and more on a healthy diet, exercise, and cessation of smoking – all of which have proven benefits with minimal down sides.

As one of the most widely prescribed medications in the world, statins rather than lifestyle, have seemingly become the treatment of choice for heart disease prevention. We believe that cholesterol-lowering statins for even younger patients may be a misguided strategy.

I’ve been in practice 30 years now. I used to believe in statins. That was just til about 20 years ago when after 10 years in practice my statin users just got heavier, became diabetic at a higher rate than non statin users. Statin users also still ended up seeing interventional cardiologists for stents or surgeons for bypass.

When I look now, most all of my senior patients in their 80s are NOT on statins, have higher cholesterol, and get this, none are diabetic and most have kept their cognitive abilities intact. This correlates well with a study that looks at octo-nonagenarians with good quality of life that all have HIGH levels of cholesterol.

So I look at cholesterol as one of the longevity markers, with the caveat being that they must also be Insulin Sensitive, which is truly the key to most cardiovascular risks.

I just posted this in response to the original article: This presumes that elevated cholesterol is indeed a causative factor in heart disease. Cholesterol is the substrate for ALL the steroid hormones -- alodosterone (fluid & mineral balance), stress & blood sugar management via cortisol, sex hormones -- not just reproduction but tissue repair & maintenance plus operations management. Testosterone is crucial for muscle maintenance -- isn't the heart a muscle? Cholesterol is the starting point for vitamin D, and the mevalonate pathway (the route statins inhibit) is also necessary for production of vitamins A, K2, and CoQ10. Cholesterol is also a key component of all cell membranes and myelin, among other roles. Focusing on one outcome is typical modern 'science-thinking', but it misses the whole picture. Maybe statins reduce risk of CVD by .5% but they increase risk for dementia, depression, homicide and suicide, cancer, diabetes, numerous other diseases, while seriously obstructing basic day to day functions. As a board certified clinical nutritionist (CCN) I studied LOTS of biochemistry with an eye to its practical implications. Weren't these basic roles covered in medical education as well? Very practically, the fat phobia mania has distracted us from the obvious. Our bodies need lipids -- fats and cholesterol -- to function. Every cell in our bodies (except mature RBCs) is capable of synthesizing cholesterol. Is this a careless oversight? When our forebears lived happily off the 'fat of the land' it's a safe bet it wasn't refined vegetable oils.