A new, costly cancer drug vs placebo; Cabozantinib in neuroendocrine tumors; How NIH funded trials can fail patients and payers

Your study of the week

John is sick, so I have big shoes to fill. Today’s study of the week is a cancer trial. I know many of you aren’t cancer doctors, and you are thinking about skipping this essay. Let me assure you: you will learn something. The trial has issues with control arm, skewed randomization (2:1), drop out and endpoints. It is a rollercoaster ride of critical appraisal. Bear with me and see if you are satisfied.

This week in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers from Harvard, took patients dying of neuroendocrine tumor (this is what Steve Jobs died of) and randomized them to a costly, toxic, branded drug or sugar pill.

Here are some facts about the study:

It was funded by the National Cancer Institute

It randomized patients with neuroendocrine tumor (pancreas and extrapancreatic) to cabozantinib 60mg or placebo

Randomization ratio was 2:1

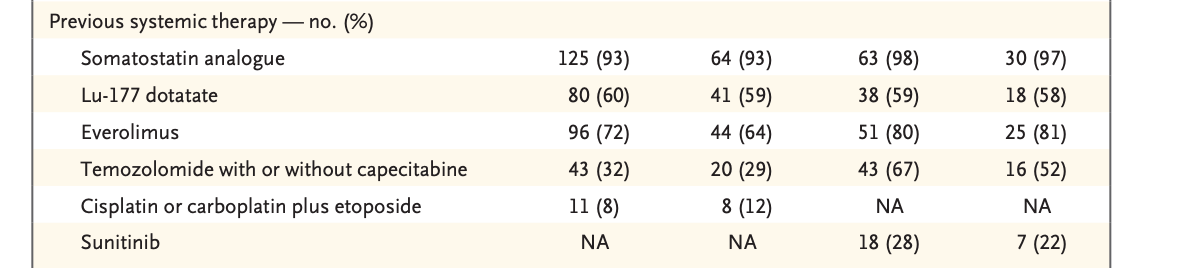

Patients had been pre-treated with some drugs used in this space, but notably most patients had not received all the drugs they could have

In 2020, investigators allowed crossover among patients initially assigned to the control arm to cabo

In 2023, investigators switched to local assessment of scans and not central assessment. (I will return to this)

The primary endpoint was progression free survival; here were the results; OS was null.

There are several issues with this study:

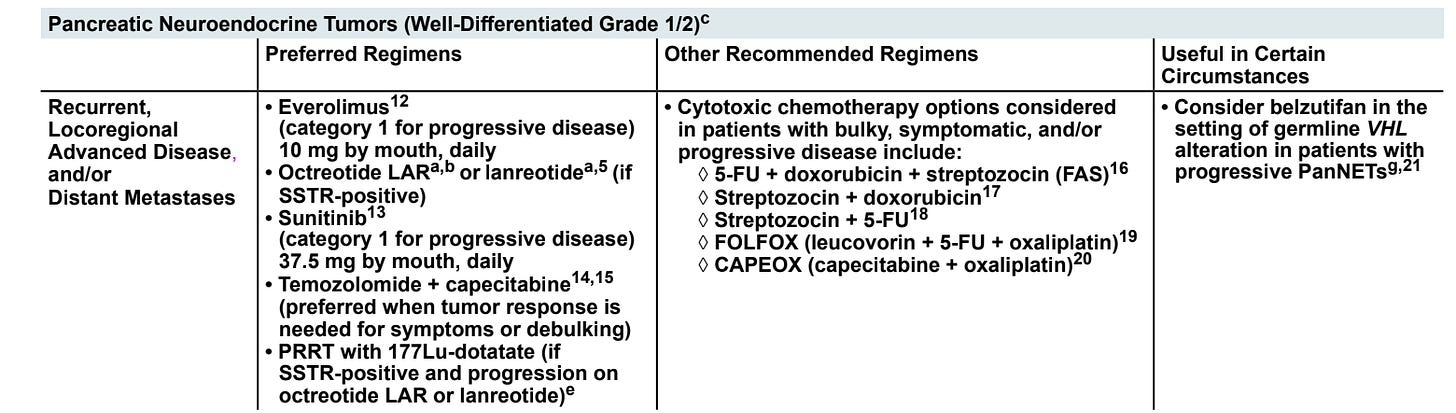

The control arm of placebo is inappropriate. In a randomized controlled trial of a cancer drug, you have to compare your new drug to the best available standard of care. If there is no standard of care, you can use placebo. But you cannot use placebo if there are proven or well accepted alternatives.

Patients who receive, for instance everolimus, and have progressive disease should get Lu-Dotatate, and not placebo. Pts who get both, should get chemo and not placebo. There are several pieces of evidence that suggest that the control arm is unethical.

NETTER 1 (the trial validating Lu-Dotatate) did not exclude patients with prior TKI , and it has a survival benefit

b. Suntinib has data supporting it’s use post chemotherapy in PNET

c. It is standard clinical practice to sequence these agents. If these same investigators let me look through their clinic charts, I guarantee they never give one drug and then put a fit, trial eligible patient on best supportive care or hospice.

d. The patients in this very study received the alternative options only after their disease worsened, presumably when they more frail and less able to tolerate the drugs. Had they not had their time wasted with placebo, this could be much higher.

e. The authors distort the evidence in the discussion

The use of these products in sequence has better evidence than other widely accepted oncologic interventions such as the Whipple surgery (no RCTs), radical cystoprostatectomy in bladder cancer (no RCTs), etc. In two cases, we have randomized data showing these agents (Sutent/ dotatate) work even with prior treatment. Moreover I am confident, like me, all of the authors routinely sequence these agents for their non trial patients. I find their statement misleading.

The protocol amendment to switch from central to local review is fishy and here is my guess what happened. Cabozantinib 60 mg is a toxic drug. Patients and doctors will easily know if they are on sugar pill or the toxic drug (side effects). Once they know, they will be annoyed if they get sugar pill and think about ways to drop out early. In 2020, the authors allowed crossover to Cabo. After this moment, imagine you are the doctor, you know that if you declare the patient has progressed (based on your read) you can switch from sugar pill to the drug. So you might do this even before the 120% benchmark of progression is reached. You might call 117%, 120%, for instance. But if we had central review of scans that would mean that this entire patient would be considered as having ‘not progressed’ and have to be censored entirely— a big loss of data. So the only way to correct this is to jettison central review, as they did. That’s my guess what happened. Central review had to go because it would result in massive censoring. Since the authors were dishonest about the control arm, I suspect they are hiding something here.

2:1 randomization reduces power— meaning more participants are needed than a 1:1 ratio, but is done because investigators believe that it speeds accrual (makes the trial more enticing, or gives people a better shot of getting the experimental drug. Yet, prior work from my team has shown it does not increase enrollment. Since it doesn’t speed, it is always inefficient.

Progression free survival is not a measure of what matters, but a surrogate endpoint that has a poor correlation with OS in most metastatic settings. It also has a poor correlation with quality of life.

It is incorrect to build in crossover to a experimental drug that has not shown benefit. I explain this in a prior essay. It actually makes it difficult to know if cabozantinib improves survival at all— it muddies the water. My guess is cabo worsens survival over the real alternatives. I.e. this is a rare trial where both arms suffer.

This trial was NIH funded

Here's the most appalling part of the study. This trial is 100% funded by you, the taxpayer. This is an NIH funded study.

Over the last few weeks we have seen many people lament pauses or interruptions to NIH funding. They say that cancer clinical trials might be halted if there are cuts in this space.

But what they don't say is that many cancer clinical trials are unethical. Including those run by our government. This clinical trial deprived dying cancer patients of therapies that are always given in clinical practice, and at times are supported by randomized trials. It deprived these patients of these drugs so that it could score a progression free survival win for a branded pharmaceutical drug.

Cabo 60 mg is an extremely toxic drug. I wouldn't wish it upon my worst enemy. Moreover, there is no one in this study who is cured by taking this drug. This trial strikes me as a classic example where investigators are more interested in their own careers rather than the well-being of their cancer patients.

How can we defend the status quo in oncology? How can we defend publicly funded clinical trials that are grossly negligent? In my opinion, reforms to the NCI are not only warranted, they are necessary. And the people who are panicking that we will miss out on cures are being dishonest, just as these authors are dishonest about the appropriateness of placebo control. There are many examples of unethical cancer trials funded by the government and misguided spending.

We owe it to patients and taxpayers to do better.

If you believe in Sensible Medicine, subscribe

I dug up 2022 NET guidelines

This is far from my area, but a terrific exercise in appraisal with neutral priors.

I agree that placebo is appropriate only when it is on top of standard of care. If patients in the control arm of this study were denied therapy they otherwise would have gotten in their clinical situation, that is egregious and unethical.

I agree the primary endpoint seems ridiculous, unless patients in this scenario actually care about increases in tumor size on a scan. Lack of OS benefit over 4-5 yrs may not be surprising, if such malignancies are not “curable”. But this type of endpoint smells like something that reaches statistical significance but is clinically meaningless.

I’m not sure about the objection to crossover. As long as it is analyzed as ITT to maintain randomization.

Loss of central adjudication (esp part way through a trial) is a major red flag. I can’t think of any legitimate clinical reason to do this, with any study.

The funding question is interesting. There’s a certain appeal in suggesting public funding should be used only to answer clinical questions that serve no commercial interest (such that no corporate entity would even bother asking the question ). And further, that public funding should not be used to help create profits that accrue solely to a private entity. OTOH, we are always quick to cast at least a little aspersion on positive clinical trials that are pharma funded. That does seem a little bit of a catch 22. And the climate is worse now with stories of investigator malfeasance such that even independent CRO study conduct and monitoring, and independent data analysis and manuscript generation, do not absolve all innuendo of impropriety (when results one way or another can make the difference measure in billions). On the third hand, public funding did not prevent very questionable protocol design and study conduct in this case.

With second hand awareness, I would humbly suggest that you are making a gross overgeneralization when stating “this is the” type of cancer Steve Jobs died from. His specific condition was not fully publicized and, suffice to say, he was -like people in the NIH trial you review - in a fundamentally compromised immune-metabolic state after more than one conventional treatment. Perhaps what is most deadly in cancer diagnosis and treatment is the unremitting drive of those profiting from technological determinism as if ever more powerful, more specific or polypharmacy is generically better for everyone with a particular type of tumor.

Pardon me for asking but what if the tumor is an effect rather than a cause or key etiology? Drug trials seldom establish a coherent context for study.

No matter when clinical trials are only really staged for patented tech wherein the studies are business ventures in and of themselves. There’s always a way to spin numbers if only to give people access to something new and expensive somebody thought up as something new.

Your analyses are revealing. Too bad we ignore what proves effective because drug companies can’t patent them or make a big profit.