A Social Science Perspective on Masking

What actions should people take and what policies should be put in place in settings of scientific uncertainty?

I know, I know, what can possibly be left to say on this topic? I feel like this piece by Dr. Scales is a good place to leave it as it totally recontextualizes the discussion in an interesting way. It is a little longer than many of our pieces but I think it is worth it. You now have my promise that I will never post about COVID and Masking again on Sensible Medicine. (You are, of course, welcome to purchase my forthcoming book: 1001 Essays on Masking in Healthcare Facilities. It is sure to be a bestseller.)

Adam Cifu

Sensible Medicine has precipitated a debate about masking in the setting of COVID-19. One recent piece against it wrote, “Always wearing a mask on a medical service in 2024 is an extreme measure and lies outside what should be considered acceptable professional behavior.” A thoughtful response piece countered, “I don’t see the need to speak in absolutes or inflict my masking preferences on trainees.” Adam Cifu has also written at least two pieces on masking, and other Sensible Medicine authors have also written on the practice, including one earlier this month.

I am not an expert on masking, so I do not intend to resolve the debate with this piece. As a physician/sociologist, my hope is to (re)frame the questions being asked and provide some social science and medical evidence to inform, and perhaps complicate, this polarizing debate. Instead of asking “should providers be masking or not?” I argue we should consider reframing the questions: “what actions should people take and policies put in place in settings of scientific uncertainty?” Answering that question requires not just examining medical evidence but diving into social science literatures as well. For decision making in settings of uncertainty is a question of values and weighing competing interests, and not only one of evidence.

First, let’s agree that there is uncertainty around the efficacy of masking. Dr. Cifu noted three starting assumptions in his 2022 article that are worth restating: 1. Masking in healthcare facilities reduces the transmission of respiratory infections, 2. COVID carries less risk now than it did in 2020, and 3. People do still get sick and die from COVID (though the question of risk of Long COVID with new or recurrent infection remains uncertain).

It is worth briefly touching on why there is uncertainty around whether masking prevents respiratory infections. It is because the evidence is mixed and often context dependent. Other articles have reviewed that evidence in depth, including a comprehensive review incorporating observational and RCT evidence published just last week. Plus the debate is contentious and not simply about masking. It taps into a larger controversy about evidence hierarchies and what kinds of evidence even speak to that seemingly simple question. Some on Sensible Medicine have made it clear where they stand on that debate.

Instead, the different—often implied—question (“what actions should people take and policies should be put in place in settings of scientific uncertainty?”) taps into a wealth of other evidence and literatures that can productively inform this debate. Starting with the difference between risk assessment and risk management, I’ll use two examples to show, first, how regardless of the risk assessments, individuals manage risk through clinical decision-making that is influenced by cultural values (in the context of antibiotic prescribing), and, second, how the mammogram/breast cancer screening debate is similarly split due to a lack of separation between risk assessment and risk management.

The Sensible Medicine pieces noted above often conflate key questions: “should I mask?” “should others around me be masking?” and “what should organization-wide or population-level policies on masking be?” These questions are only partially asking the efficacy question raised above. That question—“Does masking prevent infections?”—is a question of risk assessment, the scientific, usually quantitative, process of characterizing risk and benefit. These other questions are about behavior—should physicians mask? should hospitals issue mask mandates?—and therefore questions of risk management, i.e. the political and social process of making decisions that incorporate risk, amidst other priorities based on collective values. Risk assessment and management is at the heart of this disagreement (see these papers to dive more deeply). Or, put differently, risk management does not naturally flow from risk assessment, because no risk analysis is perfect and there are always assumptions and unknowns. Moreover, even when risk assessment seems clear, there are still multiple ways to manage those risks and associated tradeoffs.

Social scientists study the various structural factors, values, and preferences that come to bear on those risk management decisions. Physicians like to think “first do no harm” is a beacon. Some prefer a “better safe than sorry” approach. Both adages are actually risk management approaches that are not universally shared across cultures. The next two examples are included to highlight how cultural differences in values and priorities drive risk management decisions, even when risk assessments are relatively clear. The first is the prescribing and use of antibiotics in clinical settings and, later, the use of mammography for breast cancer screening.

The medical evidence is quite clear that high antibiotic use breeds bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Yet antibiotic prescribing practices differ starkly across geographies as people, cultures, and even medical specialties manage risk and tradeoffs differently. This is about more than just “perception gaps” where someone needs more/better education. Risk management is acknowledging that people with different cultural values, interests, and preferences will place different importance on different objectives, especially in a multicultural society. For example, the value that some people place on “peace of mind” may contribute to overdiagnosis and overtreatment in some cancers. It also may have contributed to physicians’ overprescribing of antibiotics early in Covid.

Most of this evidence comes from Europe, where two decades of national Eurobarometer surveys have shed light on correlations between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and antibiotic seeking and prescribing behaviors. Cultural values such as “uncertainty avoidance” and “power distance” (i.e., the rigidity of power hierarchies) and occasionally “masculinity” or “individualism” correlate with antibiotic seeking, prescribing and resistance rates at a country-level (this literature is vast, but some examples can be found here). Countries in northern Europe, which, on average, have higher tolerance for uncertainty and lower power distance relative to southern European countries. These historical divides run deeply and antibiotic resistance rates differ accordingly in the two regions. For example, antibiotic use and resistance patterns differ starkly across the centuries-old Protestant/Catholic divide.

These findings resonate at the local hospital level as well. Dr. Glaucomenflecken has made light of how different medical specialities have different cultural practices. But these cultural differences—again, often related to hierarchies and tolerance of uncertainty—yield real differences in antibiotic prescribing practices between internal medicine and surgical teams in hospital settings. In primary care, structures of care delivery, patient-driven factors, and physician practices all contribute to antibiotic seeking, prescribing and resistance.

Here’s the lesson: while risk analysis data is clear on when antibiotics should be used, risk management practices differ because, as some researchers put it, “antibiotic decision-making is a social process dependent on cultural and contextual factors.” Ignoring the myriad structural and cultural factors that influence decision-making will not change people’s behavior. Worse, it may backfire, alienating the very people whose behavior physicians and public health practitioners hope to positively influence. Significant literature on successful antibiotic stewardship programs suggest that taking structural, organizational and cultural factors into account is essential to make progress. Social science suggests we should expect the same when it comes to masking.

The dynamic around mammography screening is similar. In her 2023 book Mammography Wars, Asia Freidman, a sociologist at the University of Delaware, describes how the debate centers around two camps: “interventionists” and “skeptics.” Interventionists argue to start screening for breast cancers at 40, and skeptics argue the evidence supports screening at 50. There is evidence to support either position, which is partly why USPSTF guidelines vacillate on the issue (including just recently). Dr. Freedman demonstrates how the question of screening at 40 or 50 is not one of risk assessment but risk management. We know the numbers on false positives and false negatives and lives saved when screening at either 40 or 50. The risk management question is how to manage scarce resources and while improving health outcomes. Interventionists pay most attention to missed cases and false negatives, focusing on individual preferences, not missing any cancers, and concerning themselves less with overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Skeptics take a population-health perspective, acknowledging the problem of overdiagnosis while trying to achieve the maximum health benefit from screening while expending the least resources. Who is right? The point is that there is no right or wrong, only risk management decisions seeking to balance different tradeoffs. We should view masking the same way.

These examples show that human behavior—regardless of the certainty of the evidence base—comes down to often implicit risk management decisions. Risk assessment—i.e. “The science”—can only inform risk management. It cannot tell us how to weigh various trade offs, many of which Dr. Cifu previously described for masking in his 2022 Sensible Medicine piece. In other words, weighing tradeoffs is not a universal exercise. Projecting one individual’s values, identity, and preferences on other people or policy is not just impolite, but if that person is in a position of power it could be called oppression. At national levels, many consider it cultural imperialism, for “epidemiologists and the health care movement in general have a mandate to fight disease and premature death; they have no explicit mandate to change culture.”

To be clear, the question, examples, and literatures I addressed here are not the only ones with lessons we can apply to this masking debate. But, I hope this process has triggered a reflex to bring evidence back into these debates, especially evidence from social sciences. Because, whether the evidence is uncertain (as in the case of masking) or more certain (like with antibiotics or mammography), how we use that evidence is a question of values. And being explicit about what values are being prioritized in risk management decisions may help us move past acrimonious debates to more productive discussions.

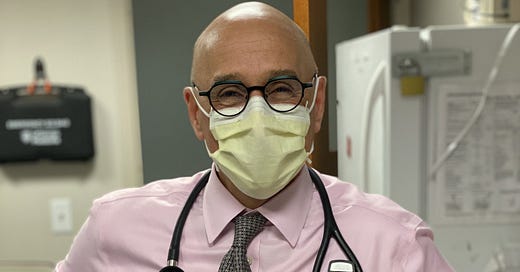

David Scales MPhil, MD, PhD is a physician and sociologist at Weill Cornell Medicine. He studies contested illnesses and medical misinformation, designing and testing community-based interventions to address information distortion in online settings.

The evidence is mixed?

Are we talking about only high quality evidence or all the evidence? Looking at only the RCTs, masks either don’t work or the benefit is subclinical. If we allow low quality evidence into the mix, then nothing is ever settled, everything seems to work, even bloodletting. Our lives are forever manipulated not by truth, but by the intuition of powerful people, either for ego or profit.

Remember how within a few weeks they went from masks don’t work, to masks will shut down the virus? Anyone with a basic understanding of science knows it doesn’t change that fast. In this case the game changing new evidence was an observational study of two hairdressers. Were they BS-ing before, after, or both?

We could have settled the question of whether masks work with a few more high quality RCTs, but that will never happen now because partitioners of intuition based medicine (IBM) have declared such tests are unethical. Since they “know” masks work, it is unethical to have an unmasked control group. Classic example of circular logic. We will have to debate this question for all eternity.

The sad truth is that intuition based medicine harms our overall health and drives up healthcare costs, lowering our standard of living. Having seen enough spectacular examples of how confounding fools high IQ people, I have come to the conclusion that most medical services probably don’t benefit the patient, and an alarming number are likely harmful.

"Projecting one individual’s values, identity, and preferences on other people or policy is not just impolite, but if that person is in a position of power it could be called oppression."

And which side of the masking debate was overwhelmingly guilty of this?

It is not lost on us that 3-4 years ago pointing out the lack of evidence for masking and calling for it to be an individual choice was harshly condemned by all those in government and the ruling medical organizations. People were refused access to public spaces, families kicked off of planes... Now, years after the issue really mattered and when the (lack of) evidence is overwhelming, there's careful justification on why we should all support individual choice.

Timing matters. Without acknowledgment and apology of the wrongs wrought by masking zealots throughout the pandemic; and a promise to stand for individual choice not just now, but the next time hysteria descends on us; arguing for individual choice after the fact rings hollow indeed.