Breakthroughs in Obesity?

The Study of the Week highlights the complexity of using trials that deliver clearly positive results.

A brief note to readers. The Study of the Week columns have remained free of pay walls. If you enjoy our work, please consider becoming a paid supporter. JMM

In past columns, we have shown readers many of the ways proponents shine favorable lights on treatments. Things like spin and bias and dubious endpoints.

Today is different. Today I will show you a drug class that works. There’s no bias, no spin, and good endpoints.

Yet, even with these positive results, doctors will still struggle to know how to use these medicines.

Obesity is one of modernity’s most pressing health issues. The statistics are staggering. More than 40% of adults and one in five children in the US are obese. (Read that again.)

Obesity creates havoc to health because it increases the risks of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and many types of cancer.

The many causes of obesity explain the lack of success in its treatment. Modern healthcare can often shred single-cause diseases. We cure problems like supra-ventricular tachycardia and appendicitis with a single procedure.

But obesity—with its mixture of metabolic conditions, environmental factors, and genetics—is a hard target for any one intervention.

STEP 1

New England Journal of Medicine published the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in adults with obesity.

Semaglutide is a GLP-1 analogue. GLP stands for glucagon-like peptide. These drugs are used to improve glucose levels in patients with diabetes, but doctors noticed that patients given these drugs lose weight. This effect seems tied to a slowing of digestion, or the speed with which food moves through the gut.

In STEP 1, investigators randomized about 1900 patients (mean BMI = 38) to either once weekly semaglutide or placebo. Both groups received counseling sessions on diet and exercise. The primary outcomes were percentage change in body weight and a weight reduction of at least 5%.

The drug clearly worked. You hardly need statistics. You can see the weight loss on this graph. The average weight loss was 12.7 kilograms, or about 28 pounds. Other related measures, such as waist circumference, blood pressure and physical functioning also improved.

There were side effects. Gastrointestinal disorders (typically nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation) were the most frequently reported events and occurred in more participants receiving semaglutide than those receiving placebo (74% vs. 48%). Gallbladder-related disorders were reported in 2.6% vs 1.2% in the semaglutide arm vs placebo.

Four Important Related Studies

→ The STEP TEENS trial enrolled 201 adolescents (mean age 15) to once weekly semaglutide vs placebo for 68 weeks. The results were similar to STEP 1: The mean change in BMI was 16 percentage points and 73% of kids in the semaglutide group vs 18% in the placebo group lost 5% of body weight. GI side effects were 62 vs 42 percent in the semaglutide vs placebo arm. Five vs zero in the active vs control arm had cholelithiasis.

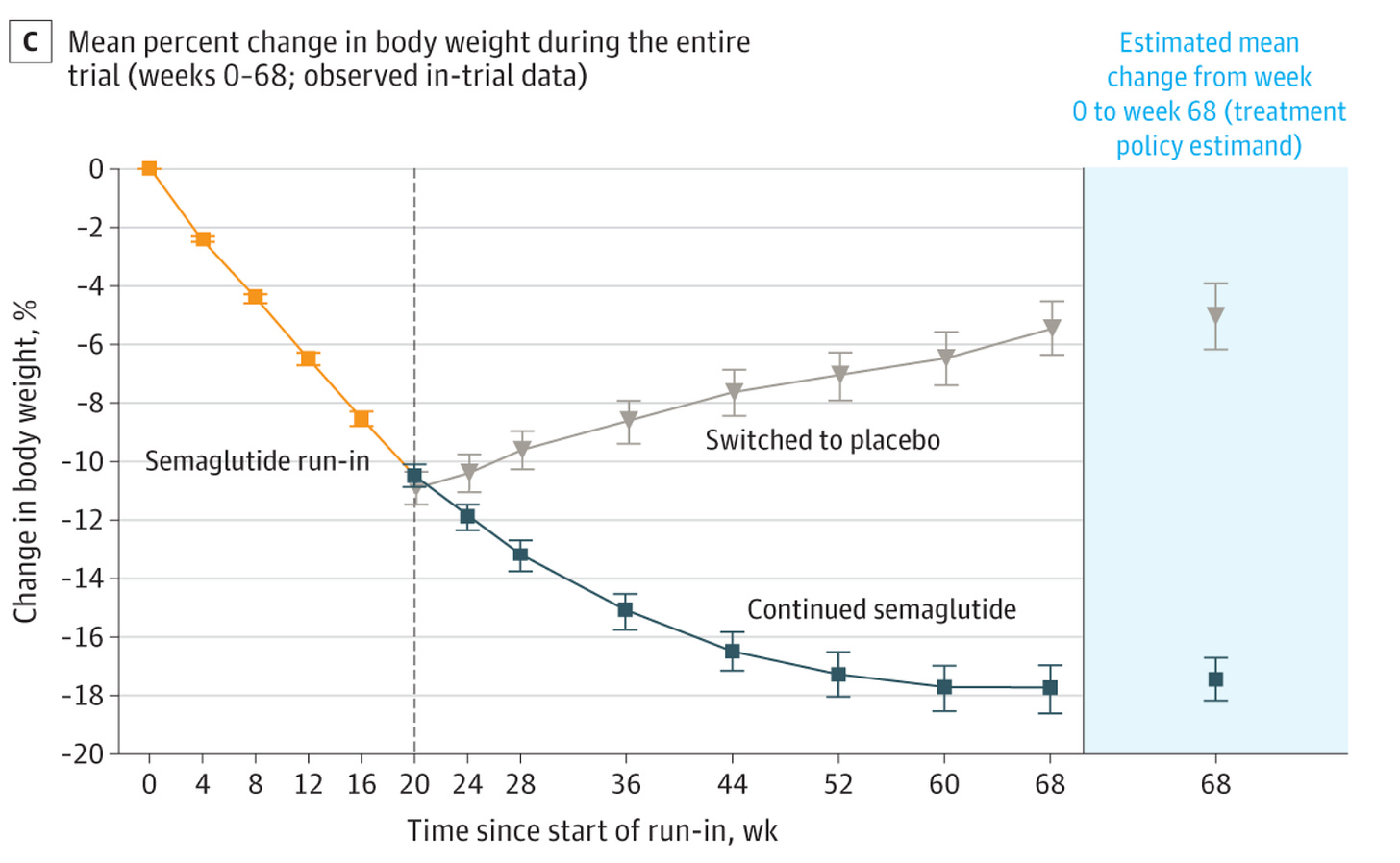

→ The STEP 4 trial used an interesting design to test the effects of withdrawal of semaglutide. About 900 patients with obesity took semaglutide during a 20-week run in period. Of these, 800 patients reached the goal dose of 2.4 mg/wk and were randomized to continued semaglutide or matched placebo.

The picture shows the clear results. In the placebo arm, weight loss stopped and weight gain accumulated.

The authors wrote: “These results emphasize the chronicity of obesity and the need for treatments that can maintain and maximize weight loss.”

→ The STEP 1 Extension Study explored the effects of treatment withdrawal after the 68 weeks in the main trial. This included only a subset of (n =327) patients in the main trial. Patients received no treatments. The results are sobering.

Tirzepatide

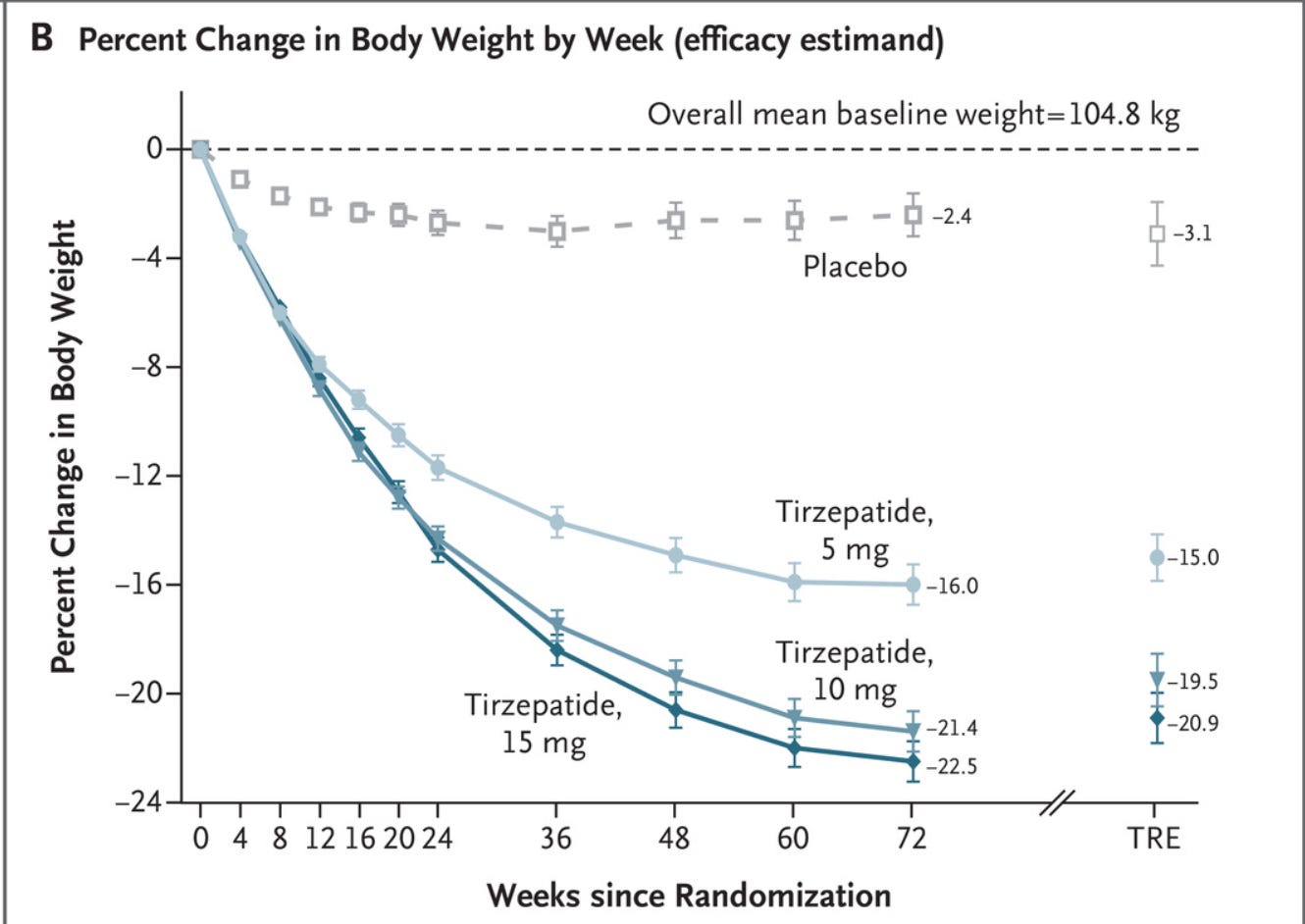

The SURMOUNT 1 trial studied a slightly different class of diabetes drug for weight loss. The once weekly injectable drug tirzepatide is both a GLP-1 agonist as well as a novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide. The latter effect is another food-stimulated hormone that regulates energy balance in the brain and fat cells.

The trial enrolled about 2500 patients with obesity who did not have diabetes to receive differing doses of active tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The endpoints were similar to the previous studies—percent changed in weight from baseline and a weight reduction of 5% or more.

Again, the graph shows the clearly positive results.

Adverse events caused treatment discontinuation in 4.3%, 7.1%, 6.2%, and 2.6% of participants receiving 5-mg, 10-mg, and 15-mg tirzepatide doses and placebo, respectively. And the most common adverse effect was gastrointestinal.

Three Obvious Observations

First is that these drugs clearly cause weight loss against a placebo. The degree of gain is similar to that seen in weight loss surgery. And with that weight loss comes improvements in important cardiometabolic measures such as blood pressure and blood sugar levels. This is really important.

The second consistency is that the mechanism of action (slowing of absorption) leads to the main side effects—gastrointestinal. Though less than ideal, these side effects are tolerable for most.

Sadly, the third consistency is that weight loss seems dependent on continuing the drugs.

This highlights one of the main limits of trials: drugs and devices are tested in short-term trials (years) but are often continued for decades. It’s important to know how a treatment works over the short course of a trial, but you’d like to be able to extrapolate those effects over the long-term (a good example is an internal defibrillator for the prevention of sudden death).

Summary

While these are hugely positive results, there are many uncertainties.

Are there long-term adverse effects? What are the unknown unknowns? These are especially important when treating kids with obesity.

Another uncertainty is why the effect seems so dependent on the drug? Why is there no click?

What I mean is that patients that I have seen who have lost weight and maintained it with lifestyle change have something click. That something prevents them from ever returning to their previous ways.

This intervention seems devoid of that click. While it may be possible for patients to take a drug like this for decades, to me, that seem less than ideal.

Perhaps this is just the first or second inning of treating obesity. We can hope for that.

Because obesity is one of the greatest threats to human health in the modern era.

This topic of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist also deserves its own Sensible Medicine podcast for the rampant obesity and diabetes epidemic we see in first world countries.

Certainly impressive results. Long term studies will take decades; why the reluctance to treat patients long term with GLP-1 analogues ? No such reluctance to use long term anti hypertensives, insulin, antidepressants, etc. Seems still a stigma of obesity treatment. As if the “click” refers to an individual having the moral strength to change their eating habits rather than a physiologic event.