CLOSURE AF - A Sobering Study on Left Atrial Appendage Closure from AHA

The study of the week looks at the CLOSURE AF trial, which was presented last weekend at AHA.

The CLOSURE AF trial compared catheter-based left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) to “best medical therapy” in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and high stroke and bleeding risk.

It’s an important trial because over 500,000 of these devices have been placed since approval more than a decade ago. I’ve long argued that the seminal trials were not persuasive, and that no new evidence has emerged to change my view.

The putative benefit of LAAC is that patients can get adequate stroke prevention and less bleeding because oral anticoagulation can be stopped. It would be great if it worked.

But the seminal trials were dubious. PROTECT AF (LAAC vs warfarin) was rejected by FDA. PREVAIL (LAAC vs warfarin) missed its first co-primary efficacy endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism and CV death because of higher rates of strokes in the LAAC arm.

No matter, proponents say the device has iterated since 2015. This is true, but OAC has also improved as we now lean most on direct acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC)—which provide lower bleeding rates and improved stroke protection.

The Trial

CLOSURE AF was an investigator-initiated trial in Germany. Two important facts: the trial was non-industry funded and Germany was one of the earliest adopters of LAAC.

About 900 patients were randomized at 42 centers in Germany. LAAC devices could have been from 3 of the main vendors. Notably, the latest version of Watchman was used in approximately half the patients. The best medical therapy arm mostly consisted of DOACs, though, 10% did not receive any anticoagulant. (*I like the pragmatic nature of the trial—ie. both groups allowed for physician decision making, which increases generalizability.)

The authors succeeded in enrolling high risk patients. The average age was 79 years, and average CHADSVASC score was 5.2. (*This is also a strength because in the US, LAAC is increasingly done in older patients with multiple conditions.)

Trial conduct, aka, internal validity, was excellent. In the LAAC arm, successful LAAC implant was achieved in 98% of patients, and in the medical arm, the bad combination of antiplatelet/OAC combination was kept low.

CLOSURE AF used a non-inferiority design. That is: was LAAC (a permanent solution) as good or only slightly worse than the established therapy of OAC?

I did not love the primary endpoint of a composite of stroke, systemic embolism, cardiovascular or unexplained death, or major bleeding. The trial used a noninferiority design with a margin of 1.3.

Maybe you can identify my two concerns with this endpoint? One is that CV death is not likely to be affected by either strategy; the other is that it includes efficacy endpoints (thrombosis) and safety (bleeding), and they tend to go in opposite directions thus canceling each other out. It turns out that these concerns did not affect interpretation. Keep reading.

Trial Results

Despite this trial being done in the “home” of LAAC, in Germany, there were serious complications in the LAAC arm. Of the 414 attempted procedures, five patients had tamponade, 18 had major bleeding requiring transfusion, there was one device embolization, one procedure-related TIA, one peripheral embolism, and two deaths within 7 days of the implant.

Over 3 years of follow-up, the incidence of a primary outcome event occurred in 16.83 per 100 patient years in the LAAC arm vs 13.27 per 100 patient years in the best medical care arm. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.28 with a 95% CI ranging from 1.01-1.62. The absolute risk increase was 3.5% or a number needed to harm of 28 patients.

The noninferiority margin was 1.3 and the upper bound of the 95% CI (aka worst case) was 1.62, so noninferiority was not established. Since the lower bound was greater 1.0 we can also say that LAAC was inferior.

The components of the primary endpoint were sort of surprising. Here is a rendering of the components. The full paper is not published.

What is a bit surprising was that major bleeding was not lower in the LAAC. This despite the fact that the vast majority of the LAAC were off anticoagulation by 6 months. Bleeding is supposed to be where the LAAC shines.

My Conclusions

This is strong evidence against LAAC vs best medical therapy. It’s a nonindustry funded trial done in centers that are comfortable with LAAC—and likely proponents of the procedure. In other words, this is surely a best case for the device.

The patients were typical of those who have this procedure. So the evidence is representative of common practice. And the trialists used contemporary devices.

CLOSURE AF also favored the device by having a super-easy primary endpoint. CV death would increase noise, while efficacy and safety endpoints could have cancelled each other out, making no difference (a positive outcome in noninferiority trials) a likely outcome. But that is not what happened. Instead, everything was slightly worse with the device. No reduction in stroke. Higher bleeding. CV death was also slightly higher.

Some might say that CV death was likely noise. I would counter that maybe this is true, but a) it was also noise in the PROTECT and PREVAIL trials, but in that case, favored LAAC, and b) there were 2 deaths within 7 days after the procedure in this trial. I wonder how many were in the first 30 days. Recall that there were 18 major bleeds requiring blood transfusion. This could have led to death later than 7 days.

We should also emphasize the periprocedural events in the trial because a patient cannot exclude the risk of the procedure. A recent LAAC trial called OPTION used a primary safety endpoint excluding the procedure—leading to positive results. CLOSURE AF investigators should be lauded for choosing the least biased safety endpoint. Excluding events around the procedure is clearly a biased approach.

What about the higher bleeding rates? This was a surprise. Patients in the LAAC had their OAC stopped mostly by 6 months. Here I think that the 18 major bleeds during the procedure were a drain on total bleeding rates. There were 70 major bleeds total. 18 of 70 is a lot.

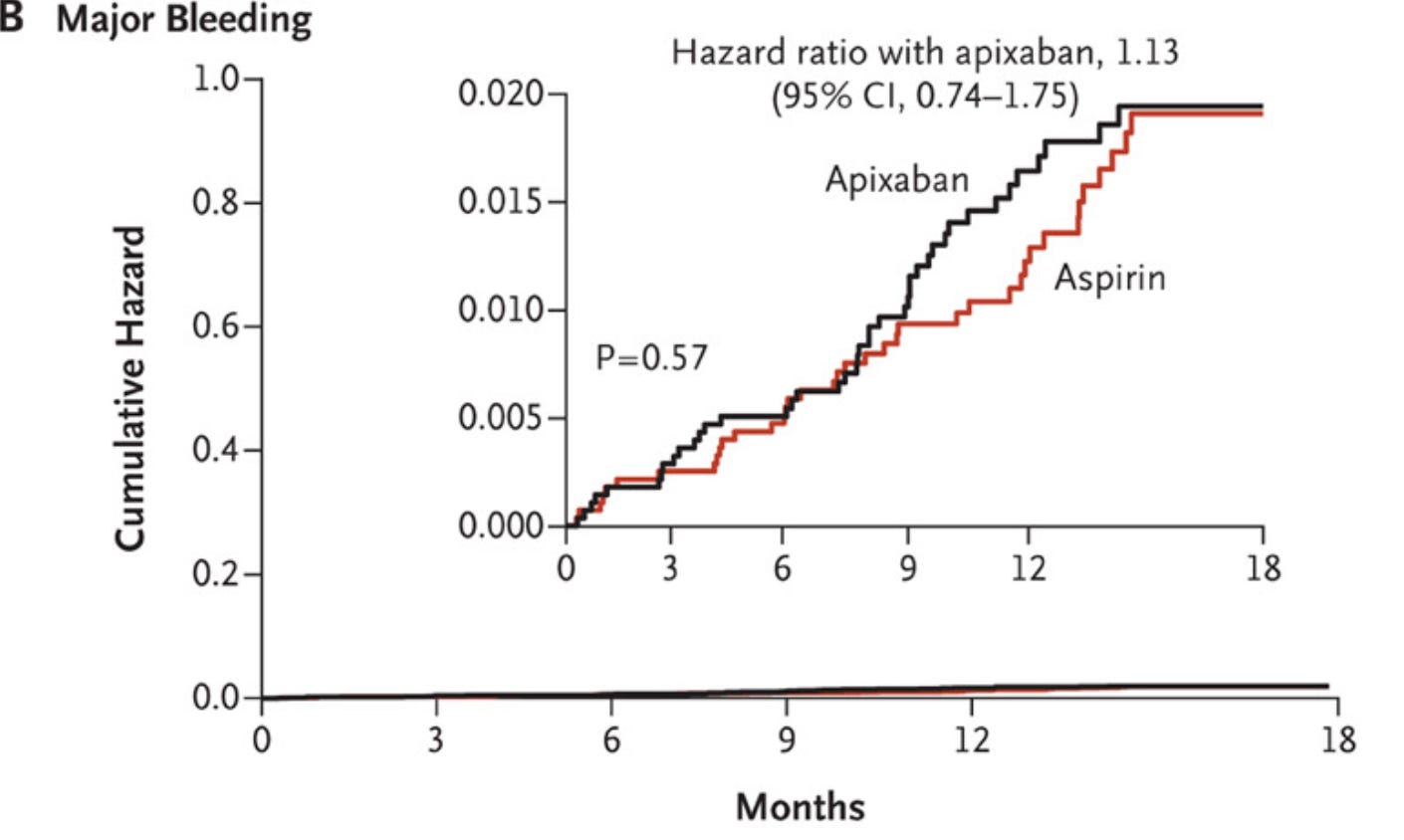

But another likely cause of higher bleeding in the LAAC arm—one underappreciated by many—is that LAAC mostly requires an antiplatelet drug, such as aspirin, and ASA can cause major bleeding. Many think it’s safer than DOACs. But that may not be true. Here is the graph of major bleeding in the AVERROES trial of apixaban vs aspirin. No real difference.

Conclusion:

Our beliefs about LAAC should have been pessimistic going into the trial. CLOSURE AF finds extremely pessimistic data—which only strengthen these priors.

Proponents will say we need to await two large industry sponsored trials—CHAMPION AF and CATALYST.

I agree, but both of these trials have primary endpoints excluding procedural events. So when they are presented we will have to look to secondary endpoints that count all safety events.

Science vs. Industry. Keep it up John.

Thank you for your ongoing attempts to slow the LAAO train and for bringing this particular trial to our attention.

I am on board 100% and quote you extensively in my recent Substack update on atrial fibrillation (https://theskepticalcardiologist.substack.com/p/what-is-new-in-the-world-of-atrial)