Coffee is great but it does not prevent dementia

I did not think it necessary to even review this study but seemingly smart people were duped by it, so here goes.

JAMA has published a whopper of a coffee study. It is the focus of the study-of-the-week.

Nine years ago, I made a plea to academics to stop doing non-randomized observational studies on things like coffee, quinoa, chocolate, saunas, and blueberries. My reasoning: these studies were so confounded as to be worthless.

I wasn’t the only frustrated reader of medical science. A few years earlier, Jonathan Schoenfeld (Harvard University) and Dr John Ioannidis (Stanford University) published a systematic cookbook review in which they found that associations with cancer have been claimed for most common food ingredients. They noted that the same food could be associated with higher or lower cancer risk. Of course, statistical support of these associations were weak. It was an elegant way of showing the massive noise present in nutritional research.

Neither of our pleas changed anything. I asked Claude to estimate how many observational nutritional studies have been published in journals since 2017, limiting to Impact Factor > 2. The answer: 45,000-85,000 studies.

The latest entry into this morass comes with two markers of potential rigor. The Journal of the American Medical Association published the study and the research team came from Harvard.

The question asked was whether coffee and tea drinkers experience less dementia in future years.

You should pause there to Stop and Think. Dementia and cognitive decline are highly complex conditions caused by many different conditions, ranging from either vascular disease, bleeding conditions, genetic disorders, toxic exposures or the combination of these. Your Bayesian prior that exposure to one food (coffee) could influence this sea of complexity should be very low.

The study used two big data bases of Nurses and Physicians, totalling more than 130k adults. (Editor’s note: do not be fooled by the large numbers; large numbers do not preclude systemic bias.)

Now the research team have essentially two groups: self-reported coffee users and non-users. They compare outcomes, which in this case is dementia incidence. Of course, users and non-users of coffee have many differences, so the researchers do adjustments in the attempt to make them similar. (This is the fatal issue).

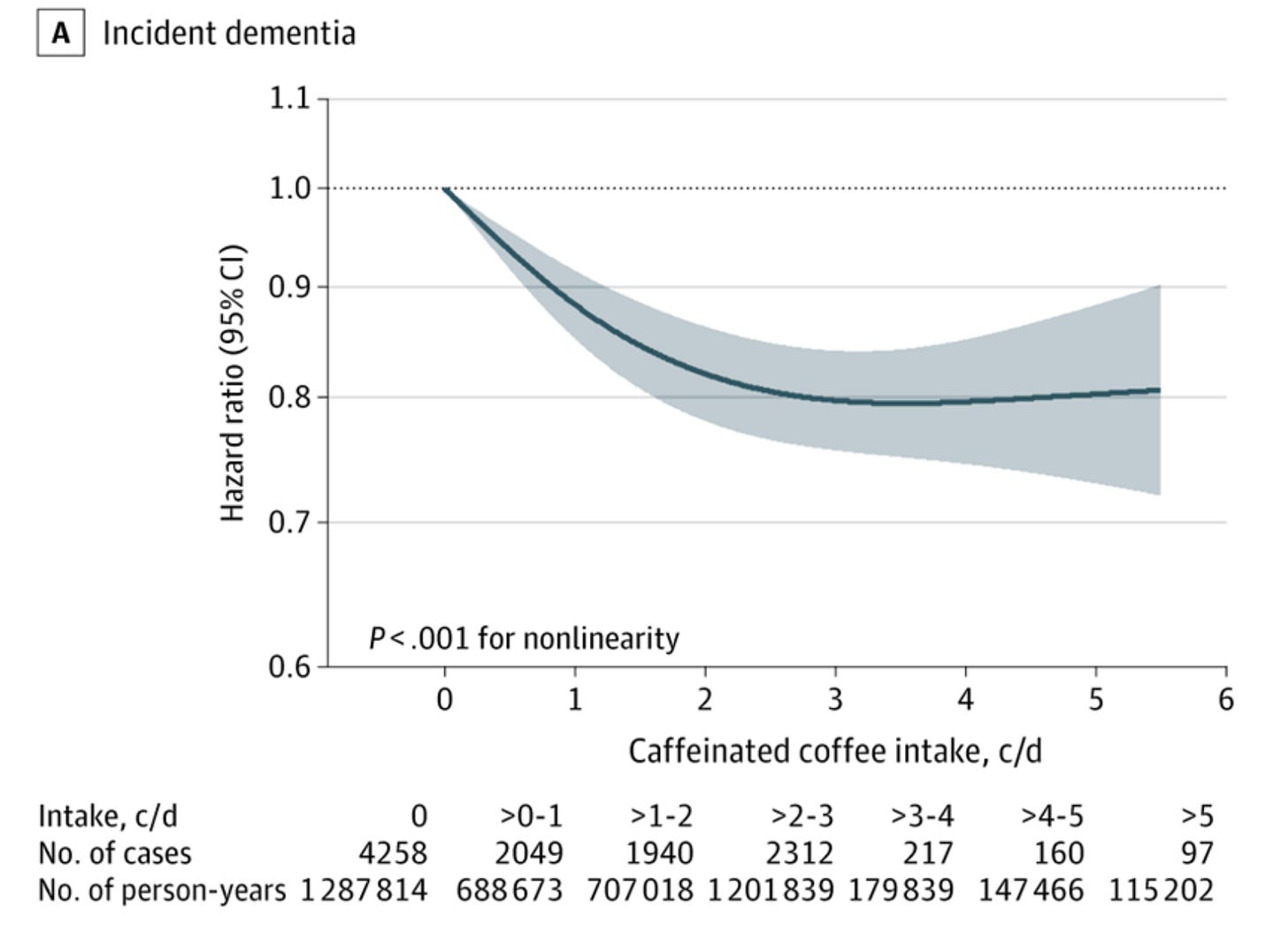

Since it’s in JAMA, you know the results were positive:

Higher caffeinated coffee intake was significantly associated with lower dementia risk (141 vs 330 cases per 100 000 person-years comparing the fourth [highest] quartile of consumption with the first [lowest] quartile; hazard ratio, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.76 to 0.89]) and lower prevalence of subjective cognitive decline (7.8% vs 9.5%, respectively; prevalence ratio, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.78 to 0.93]).

The graph shows a dose response effect (2 cups is lower risk than 1) and this gives the finding a facade of scientific validity.

The authors show even more outlandish associations when dividing the association by age.

Comparing the highest users vs lowest users HR was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.56-0.76; P < .001) among participants < 75 years of age and the HR was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.75-0.88; P < .001) among participants older than 75.

I will address this in my comments. But first let’s do the media reaction.

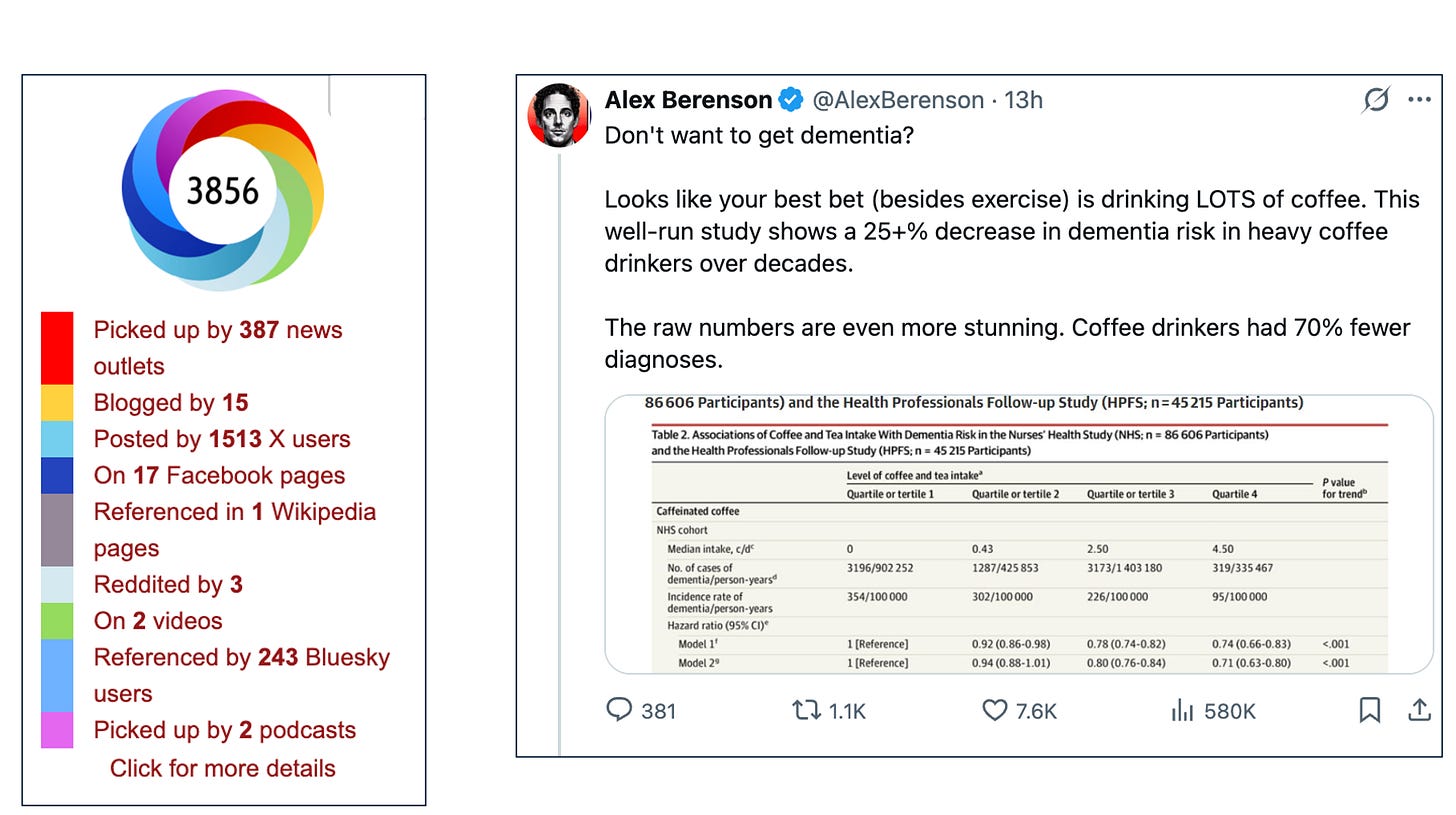

The media reaction is stunning. Nearly 400 news outlets and 1500 X users mentioned the study. I scanned the news stories; almost all were positive.

The shock for me was independent journalist Alex Berenson, one of the more popular independent journalists. Alex has impressed me with his analysis of COVID and his concerns about the danger of marijuana use. He’s a strong thinker. So I was shocked that he was taken by this study. I replied to him and he asked me to explain. (Note that his Tweet has been viewed 580k times as of this morning.)

My Comments

Nearly every study like this are flawed by confounding factors. Namely, that coffee drinkers have other characteristics that have protective effects on dementia. Maybe they exercise more, drink less alcohol or do any number of things that affect dementia.

Your counter is, John, they adjust for baseline differences, which, essentially, simulates randomization.

The problem is that researchers can only adjust based on what gets in a spreadsheet. There are surely many other factors that do not get recorded in a spreadsheet. This is why randomization is so valuable; randomization balances both known and unknown factors. The researchers say this, but of course, it is widely ignored.

The second reason this study is surely biased is the effect size. In the overall population, the putative effect of drinking coffee is an 18% reduction of dementia. That’s one simple substance conferring an 18% reduction in a complex disease. That belies all sense of complex disease.

You still don’t believe me. Ok. Let’s look at the subgroup effect on age. They report an even larger risk reduction in older individuals with coffee consumption: a 19% reduction in caffeine users in individuals > 75 years of age.

The problem here is that if you posit that caffeine has a gradual benefit over decades, you would not expect an older person who is in the age group for cognitive decline to get an effect. Because you don’t expect caffeine to be actively treating the many pathologies of cognitive decline.

The final criticism (of any of these studies) is analytical flexibility.

We at Sensible Medicine had the great fortune to have a discussion with Dr Dana Zeraatkar from McMaster University regarding the way these studies are analyzed.

Her group famously showed using a meta-analysis of meat consumption’s effect on mortality, that there are literally a quadrillion different ways to analyze the data—and doing so yields different associations. Brian Nosek’s group has also shown this phenomenon.

This study, like all of these studies, used one method to analyze the data. But Zeraatkar et al have shown that there are thousands of other choices that could be made, which would yield different associations.

Conclusion

The three take-home messages are a) don’t be fooled by these studies, b) encourage researchers to resist the urge to perform these studies—especially with taxpayer money from NIH. And c) discourage journals from publishing these studies.

Sadly, as long as attention is the incentive to do and publish this type of exercise, we can expect more of it.

And that is why you should be reading Sensible Medicine. We are here to use these papers as teaching examples.

I agree with your counterargument.

On my second cup already this morning, however. Not taking any chances…

Wonder if there is a subset of coffee purchased at starbucks ? If you could afford $5 a drink versus rot gut …