Could we do worse than the PSA for prostate cancer screening?

You bet.

Last week a friend sent me a link to an article in The Financial Times titled, MRI scan more accurate than blood test at diagnosing prostate cancer, UK study finds. I read the article, skeptically, thinking MRI as a screening test, come on. I thought it was a piece of churnalism until I read the study itself from BMJ oncology and realized that the real story was research article.

Background

Prostate cancer screening with PSA has been controversial since its introduction. The basic problem is that although prostate cancer is the second most deadly cancer in men in the US, “more men die with prostate cancer than of prostate cancer.” Thus, a screening test is almost guaranteed to lead to overdiagnosis or, at the very least, unnecessary evaluations in many of the men who are screened. The difficulty of prostate cancer screening is amplified by the fact that our treatment for prostate cancer remains morbid, with many of the men who are “cured” of their cancer living with incontinence and/or erectile dysfunction.

We have gotten better at prostate cancer screening. Improved blood tests (the free PSA) and MRI scanning means fewer men go from an elevated PSA to a biopsy. Improved pathological grading and MRI as a non-invasive means of monitoring diagnosed cancer means that fewer men with prostate cancer who don’t need their cancer treated are treated.

Currently, the USPSTF gives PSA based prostate cancer screening a rating of C for men 55-69 and D for men over 70.

Design

The BMJ Oncology article is billed as a prospective study designed to assess the feasibility of a screening approach using PSA density and prostate MRI. (I’ll criticize this later). Men between the ages of 50 and 75 from eight GP practices were randomly selected for invitation to a screening MRI and PSA density. Those with a positive MRI and/or elevated PSA density underwent prostate biopsy.

Results

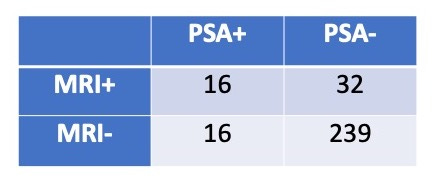

2096 men were invited to participate, 457 (22%) responded and 303 (14%) completed both screening tests. The following 2X2 table shows the number of men with positive and negative tests.

As you can see from the table above, 64 of the 303 men (21%) were referred for biopsy. The rate of clinically significant cancer (considered a prostate biopsy with a Gleason’s grade 7) for each group was not given but of the 48 men with a positive screening MRI, 25 (52%) had clinically significant cancer. Of the 16 men who had a negative MRI but a raised PSA density, 4 men (25%) had clinically significant cancer.

Analysis

I have to say, I have no idea what to make of this study. I’ve got five main concerns:

1. Proving that a screening test is effective remarkably difficult. I wrote a bit of a primer for Sensible Medicine back in February. This article shows that MRI (or MRI with PSA density) detects more cancer than PSA density. We don’t do cancer screening to find cancer, we do it to decrease mortality. This article makes no effort at showing that using MRI is better than the minimally effective strategy of PSA screening.

2. This article is billed as “feasibility” trial, but it is not even that. A trial is not necessary to know that MRI is not a feasible screening test. We do not have nearly enough MRI machines to use them for disease screening. In most countries, the wait-time for diagnostic MRIs is unreasonably long. Not to mention that a prostate MRI rivals colonoscopy and mammography as an unpleasant test.

3. The spectrum bias for this study is remarkable. Fourteen percent of invited men completed the trial. Why should we believe that these men are a representable sample. (Oh, and black men enrolled at 20% the rate of white men.)

4. Twenty one percent of the men screened were referred for biopsy. Sound high? Absolutely. Imagine an unpleasant screening test that requires a 1 in 5 people who are screened go on to an even more unpleasant test? This rate is probably related to the spectrum bias noted above.

5. And, PSA density is not the standard screening tests. PSA is the standard test.

Why was this study done? Why was it published?

Your point that ‘we don’t screen to find cancer, we screen to reduce mortality’ is crucial. It is also something that fails to be understood not only by the vast majority of the general population but also by most doctors, both GPs and specialists. Unfortunately, the ‘test’ has become something of a popular marker for ‘good medical care’ in the population: test=good, more tests=better and more expensive tests=more betterer! I think this is what drives these studies. ‘Why was it done’ is an excellent question, because MRI in this setting (and probably any other), as you point out, fulfils none of the criteria a good screening test requires: it should be cheap, readily available, not overly invasive or unpleasant, find disease that is treatable with methods that are acceptable and that decrease mortality. The ‘it’s nice to know’ doesn’t cut it for screening; never has, never will, as all it leads to is over-investigation and psychosocial/physical morbidity. This study has nothing to contribute to disease screening but is probably all about our obsession and worship of ‘the test’. RIP intelligent clinical medicine.

Yes, we can do worse. Mammograms also have a high false positive screenibg rate, often leading to more testing and biopsies and unnecessary treatment for many women. Some recent analyses even estimate that more women are harmed than saved by a mammogram. Even crazier in my view is that the acreening test involves repeatedly radiating tissue that is prone to cancee already. Screening mammograms generate a lot of downstream revenue for hospital systems hence the direct to consumer advertising and mobile mammography units. f you try to respectfully decline, the pressure to participate is coercive. Some women welcome them, so I do not advocate getting rid of them, but it should be optional screening in light of current uncertainties . Would love to hear your thoughts on the current data regarding mammography.