Friday Reflection 12: This Job Might Just Kill Me

or maybe make me healthier

CI is a 22-year-old medical student presenting to a urologist with dysuria (painful urination). He was referred by a doctor he saw in the student care clinic. He has no urethral discharge, pyuria (cloudy urine), or risk factors for sexually transmitted infections. The symptoms happen intermittently, a few times each week.

“Imagine you end up going into orthopedic surgery”, my interviewer said. “You will use bone drills in the operating room that aerosolize bone and blood. Would you care for patients with AIDS?”[i] A graphic way of asking this question but certainly not the only way. It was a common one on the medical school interview trail in the winter of 1989-1990. HIV was a threat to the health of physicians. There were cases of healthcare workers infected via needle sticks by this, at the time, reliably fatal virus. HIV infection was the only way I imagined my career choice could affect my health and my attitude towards my health. How pathetically wrong I was.

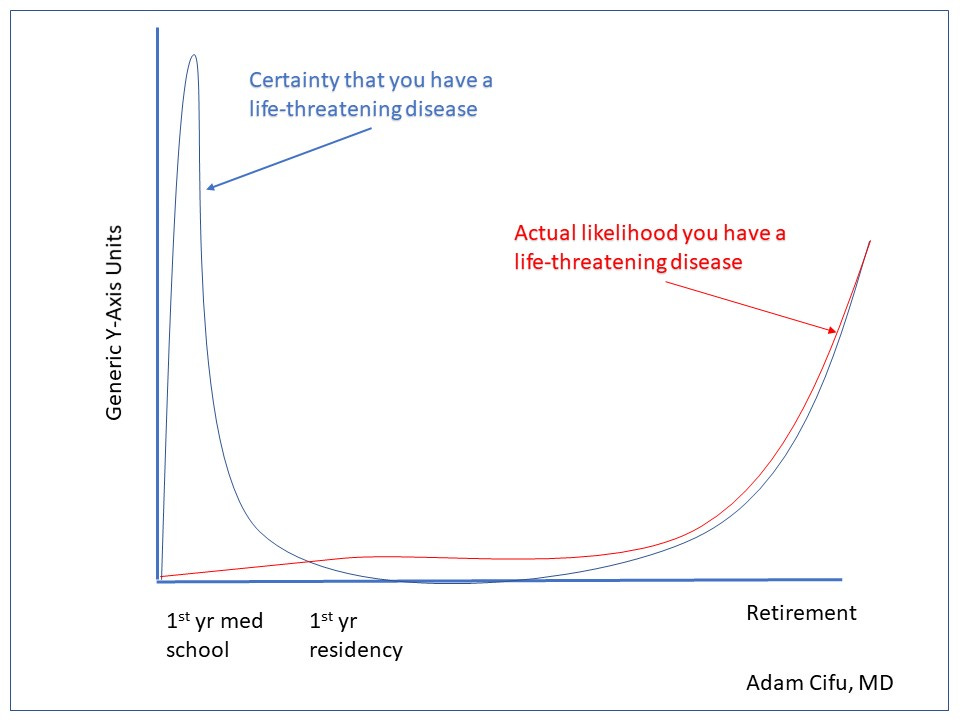

The initial health impact of a medical career is trivial and kind of humorous -- medical education practically guarantees you a case of second-year-itis. This syndrome, which I’d like to rename as “medical student specific somatoform disorder” — M3SD — manifests itself as an anxious medical student convinced he or she has developed a recently learned disease.

CI was a classmate of mine, a dedicated student who had recently aced his microbiology course. He made an appointment in the student health clinic with a troublesome symptom: dysuria. Although he had no urethral discharge, no risk factors for a sexually transmitted infection and the symptoms were intermittent, he was sure he had chlamydia urethritis. The doctor he saw did a prostate exam, collected a urine sample and preformed a urethral swab. All the results were normal. CI was then referred to a urologist who performed an exotic diagnostic test, a careful medical history. He determined that CI experienced the symptoms only on Tuesday and Friday afternoons. A bit more digging revealed that these were the days he lunched at Maryums, a wonderful Middle Eastern restaurant across from his apartment building. Maryums was known for its generously spiced garlic chicken.[ii] CI changed to less heavily spiced lunches with rapid resolution of his symptoms.[iii]

Medical trainees outgrow M3SD. Once I stopped constantly imagining that I’d contracted new diseases, I rediscovered my adolescent sense of immortality. Nothing makes you feel invulnerable like enjoying youthful good health while surrounded by illness and death. Residents remain well, protected by their age, fitness and social supports. When they do get sick, youth generally assures benign diagnoses. In recovery, they become even more confident in their robust constitutions.

With time, my knowledge of medicine fed my faith that I was indestructible. As I gained clinical experience, I recognized the rarity of the conditions that I feared most. These “pre-test probabilities” become part of the system 1 thinking of the medical trainee. It allows us to write off the eyelid twitch and polyuria as the result of too much caffeine rather than as the first symptom of a brain tumor causing diabetes insipidus. We see patients who come in expecting the worst; patients who have googled their symptoms and fixated on the ghastliest etiologies. Our ability to assuage these fears with an accurate, and usually harmless cause leads to confidence in our mastery of diagnosis. We extrapolate a mastery of the diagnostic arts to a mastery of the diseases themselves.

An occasional consequence of our delusions of imperviousness is denial. It becomes impossible to imagine that the lingering ache, troublesome cough, or addiction could be something serious. Many physicians do not have doctors during training, self-prescribing the occasional antibiotic or curb-siding friends and colleagues.[iv] We have all listened to a story of a fellow physician who waited far too long to seek care for what, in retrospect, seemed like obvious red flags.

When I was diagnosed with a chronic illness in my early 30’s, I realized another advantage of my career choice. I had a good sense of my diagnosis (though I did spend every day suppressing the idea that it could be something much worse) and knew whom I needed to see. A couple of phone calls and I had an evaluation scheduled within days. This kind of access is something that nobody outside the field – no matter where they live or how rich, well-insured, or connected they are – can even dream of.

Which brings up another advantage: wealth. The greatest correlate to ill health and shortened life expectancy anywhere in the world is poverty. With each year of training, the young physician guarantees him or herself a lifetime of employment, health insurance, and some degree of wealth.

With age (and diagnoses added to your problem list), the physician’s confidence in eternal health begins to wane. Our youthful colleagues are replaced by ones with grayer — or absent — hair. The patients we see in our outpatient practices, patients who used be “old,” are now our own age. Inside and outside our practices we see that contemporaries actually do become seriously ill. Our knowledge of medicine now makes us uncomfortably aware of what is ahead.

These days, the self-assurance that allowed me to whistle through the graveyard (my workplace), has passed. I now feel as if I am tiptoeing through a minefield. When I give a ruinous diagnosis to a patient, I find myself asking the healthy person’s version of “why me?” “Why not me?” My growing knowledge of the natural history of diseases reminds me that each new injury or minor disability may very well be with me for the rest of my days — days that now actually seem finite. I try to see this insight as a gift that allows me to keep my aches and pains in perspective and fully appreciate my health. I try to remark on the days where everything feels fine.[v]

We older physicians become a special type of patient, the doctor/patient. Though our profession affords us enviable access to healthcare, it is hard to find the right doctor. The rare physician seeks out, let alone succeeds in, the role of caring for the aging, experienced, and (often) opinionated doctor. When we find that doctor, however, the collegial and collaborative management of one’s health can be terrifically rewarding and the relationship truly special.

Beyond the anecdotes of colleagues, I don’t have much to support what I have written. We have research on burnout, mental health challenges, and suicide rates but little systematic data on physicians’ views of their own health or frequency of seeing doctors. It is probably true that we are healthier than the population at large but not as healthy as we think.

Entering the field of medicine, most students know that they are accepting some small risk in caring for people who might be infectious or violent. They also recognize that they are setting themselves up for nearly a decade (at least) of sleep deprivation. I think that few really understand the subtle but profound ways that their profession will affect their health. Our chosen field entangles us in the healthcare of near strangers and alters our relationship with our own healthcare. We begin with an obsessive, nearly comical, level of concern; proceed through years of perceived invincibility and mastery; and only later reach détente and appreciation. Perhaps the least recognized reward the medical profession bestows is insight into our own health and well-being.

[i] For those playing along at home, the correct answer was “yes, with universal precautions.”

[ii] I did some fact checking of this one. There is actually no literature of garlic metabolites irritating the urethra. This is either a case report waiting to be written or another example of the placebo effect of a well-placed suggestion.

[iii] I don’t want to break the thread, but I like these stories so much I need to add one more. A colleague once visited an oncologist for a week of fatigue and lymphadenopathy. Her (incorrect) diagnosis: lymphoma; the oncologist’s (correct) diagnosis: mononucleosis. What makes the story memorable is how my colleague acquired the infection. She had recently babysat for the oncologist’s daughter who was home sick with, you guessed it, mono.

[iv] This despite the Oslerian adage that a doctor who cares for himself has a fool for a patient.

[v] I remark to myself. I can’t imagine anyone else would be terribly interested.

The only advantage to have been born with chronic health issues that were supposed to shorten my life is KNOWING that Osler was correct when stating “the best way to live happily is to develop a terminal disease and then take care of it”. It’s not an exact quote nor am I positive that Osler said it, but here I am at 57 - and thrilled that I will continue to die living rather than live dying.

Great piece! It takes me back to my days in nursing school when I diagnosed myself as being pregnant, though I had been celibate for almost a year. But all the other signs lined up perfectly! So strange.

As a retired nurse I see how much my life with sick and dying people has enriched my own experience of aging. I’m very grateful for pain free days, and I call on my memories of people suffering chronic pain to keep me strong when pain threatens to overwhelm me. I saw first hand the kind of courageous benevolence some people carried with them into the most horrendous illnesses. They were and are my best teachers. It’s very hard being human, but having had a career that let me be close to all kinds of people dealing with illness and dying makes the struggles more bearable.