From Guideline Recommendations to Articulated Harms and Benefits

In the ideal, clinical guidelines incorporate evidence and expert opinion and enable clinicians to make evidence-based decisions without having to read the primary literature. These guidelines serve as an authority, defining high-quality care and how medical care should be delivered. Clinical guidelines have potential benefits: improved health outcomes, consistency of care, and reduced uncertainty (for the clinician).

The potential harms of clinical guidelines are recognized (1, 2). Population-based recommendations may not consider the needs of individual patients and can lead to “wrong impressions about the relative importance of diseases and the effectiveness of interventions”. Guidelines can mislead doctors by simplifying the complexity of medicine and clinical judgment. They can also be harmful when cited as evidence in malpractice litigation.

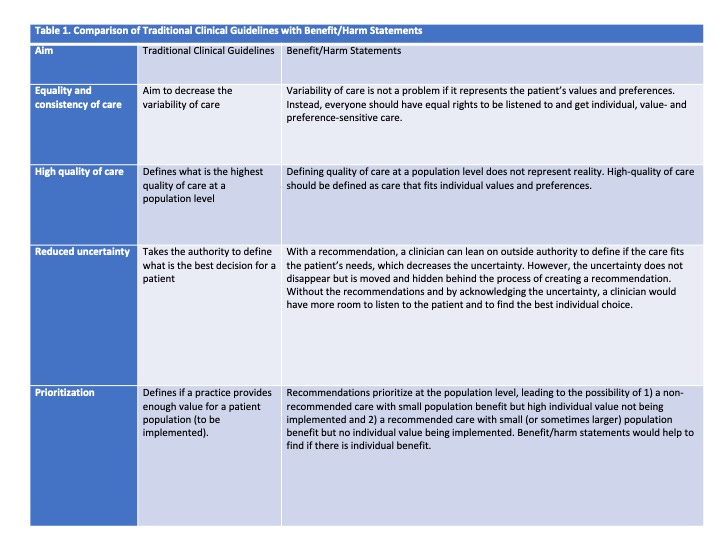

Recommendations fall short of achieving their intended aims for better care

Traditional clinical guidelines aim to improve the quality, equity, and consistency of care. They may also help clinicians reduce uncertainty and prioritize treatments. These goals are admirable, but guidelines may fall short. The harm that clinical guideline may cause can be at the individual level as well as at a more general one because it is uncertain how well the value judgments in the recommendations represent those of a population.

Both clinicians and patients often have unrealistically positive assumptions about the benefits of medical treatments and tests, and guidelines perpetuate these assumptions by recommending treatments and tests that have small or unclear benefits. Clinical guidelines have made physicians fear malpractice litigations if they deviate from the recommendations. These recommendations also serve as the basis for quality improvement interventions. But do guidelines lead to high-quality care? By decreasing autonomy and maintaining unrealistic assumptions, recommendations could lead to worse individual choices and inefficiencies in healthcare.

An example: A patient with suspected otitis media is usually seen in person and may receive antibiotic treatment. However, acknowledging the benefits and harms, a clinician and a patient might decide against a visit. Patients with mild symptoms might decline a visit even acknowledging the potential benefit of initiating antibiotics early. This is often a reasonable decision as about 80% of the ear pain resolves after three days.

Similarly, though guidelines recommend treating all patients with hypertension, it is unlikely that that choice fits the values and preferences of individual patients. Therefore, aiming for guideline adherence (and guideline-consistent care) may not be preferable, waste limited resources and make it more difficult to take care of patients who most need treatment .

Furthermore, it is uncertain whether implementing guidelines even improves patient health.

A critical part of evidence-based medicine is acknowledging the values and preferences of patients. Guidelines rarely provide sufficient information on the benefits and harms of treatment options (1, 2). As the information is often difficult to approach and translate for patients, it is not surprising that engaging patients in decision-making (or shared decision-making) is difficult. If the information is unavailable and recommendation-based treatment is given as the only option, the clinician might have no other option than to lean on the outside authority of guidelines.

This type of practice could be detrimental to the patient-doctor relationship. Shared decision-making works then doctors do not seek to persuade but rather inform and support patient autonomy. Therefore, we should enable the informing and shared decisions with the information of benefits and harms rather than steer physicians towards ready-made choices with recommendations.

Guidelines without recommendations

An alternative approach to standard clinical guidelines would be clinical guidelines without recommendations. These would include short benefit/harm statements. The adoption of such guidelines could lead to a higher quality of care, more sustainable healthcare, and support clinicians in understanding patient preferences.

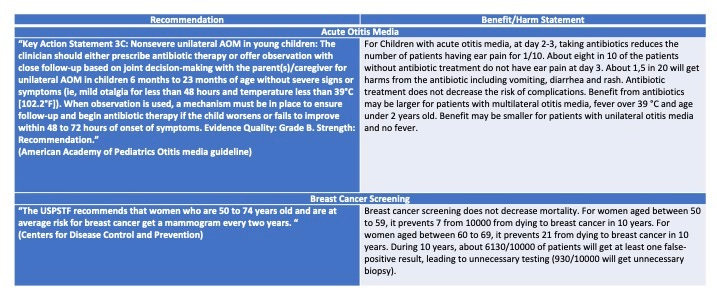

Table 2 provides two examples of what this could mean in practice. Instead of a ready-made choice, guidelines would nudge towards an informed choice.

Efficient resource allocation can only occur within the physician-patient interaction. Guidelines already recommend practices that are not sustainable given the limited healthcare resources. As we need to prioritize between effective treatments, we should ensure that prioritization is done as close to the patient as possible.

There may be downsides to reducing the use of standard clinical guidelines. These include an increase in therapeutic uncertainty, particularly for young clinicians. Therefore, training would need to focus on the ability to support individual value-based care. Instead of “what should be done and in what circumstances” we should teach “what is the value (considering benefits and harms) of the treatment to the individual patient” and how to listen and achieve the best individual choice.

Conclusions

Traditional clinical guidelines have probably provided some benefits to patient care. Replacing them with benefit/harm statements could lead to even higher quality, more sustainable care. Increased autonomy would give clinicians more room to listen and involve the patient in care. It should be possible to compare patient outcomes – both clinical and satisfaction with care – in patients cared for by physicians following traditional guidelines and those using benefit/harm statements.

Let’s have the courage to trust the clinician’s and patient’s ability to make the best individual choice.

Aleksi Raudasoja is an editor in Finnish Current Care Guidelines and is the responsible editor of Choosing Wisely recommendations. Dr. Raudasoja is finalizing his PhD on de-implementation strategies and low-value care.

This I believe is one of our best contributions. Thank you AR. I agree with it 100%

' Let’s have the courage to trust the clinician’s and patient’s ability to make the best individual choice. '

From my lay perspective I fully agree.

I see guidelines as an opportunity for pharma and others to have a resident salesforce at zero cost.

The concept of SDM is flawed, we need personalised care. As a patient I make the decision, either within the consultation or later outside (eg poor meds adherence, not attending tests etc) ; the hcp provides the evidence.