Gaming Survival with Poor Post-protocol Care

A Sensible Medicine Guest Post

This post gives a nice summary of a recent article that Dr. Olivier published with Giuseppe Salfi. In the article, the authors point out a common and particularly troublesome design issue in oncology trials. The article is linked below, and Dr. Olivier includes a video of a conversation recorded among the research team.

Adam Cifu

Would it be surprising if a patient enrolled in a trial did not receive the best care once the trial ended? The question may seem strange, yet this situation is widespread in oncology trials leading to marketing authorization (approvals). The reason it happens is deeply problematic.

Why does it matter? Because when such situations occur, they can artificially create or inflate survival benefits — benefits that would not have appeared if patients had received proper care afterwards.

In a new paper out in the European Journal of Cancer, we highlight that not only is suboptimal post-protocol care pervasive, but we also show that it may reward certain strategies, in terms of preferential approval and/or higher guidelines recommendations.

What is post-protocol care (and crossover)?

In randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in oncology, there are different situations. For early cancers that have been removed (mostly by surgery), patients may be offered what is called “adjuvant” therapy, to prevent or delay recurrence and ideally to increase the fraction of patients cured in the long term. The other situation is patients with advanced diseases, like metastatic cancer. In both situations, the care the patients will be receiving after the protocol-assigned therapy is what we call “post-protocol care”.

Crossover is a subtype of post-protocol care, often meaning that control-arm patients are offered the experimental therapy upon progression. Terms like “crossover”, “post-recurrence care”, and “subsequent therapy” are sometimes used interchangeably, but they are not exact synonyms.

An example – the ADAURA trial

When control-arm patients lack optimal post-protocol care, it may artificially drive, at least in part, an overall survival benefit for the experimental therapy.

Patients with EGFR(epidermal growth factor receptor)-mutated lung cancer, after resection, may or may not recur. This is the situation where adjuvant therapy may offer a benefit. In the ADAURA trial, patients with resected EGFR-mutated lung cancer were offered either three years of adjuvant osimertinib or placebo. When the trial began enrolling patients in 2015, it was already known that EGFR-TKIs (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) were the best first-line systemic therapy for relapsed patients. Moreover, during ADAURA accrual, the FLAURA trial showed that osimertinib — a third-generation EGFR-TKI — was the best first-line systemic therapy.

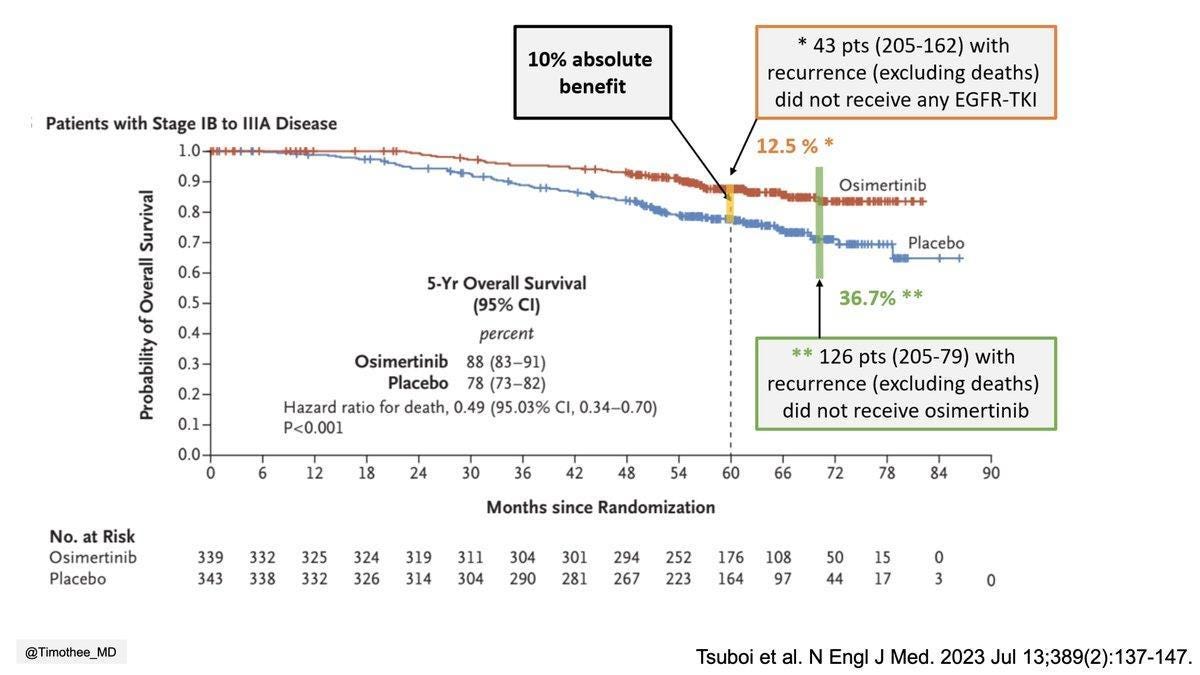

Now, let’s see what happened in the Adaura trial:

In short, there is a 5-year 10% absolute survival benefit; however, 36.7% of patients in the control arm relapsed and did not receive osimertinib. Being less restrictive, if you consider any EGFR-TKI, rather than just osimertinib, 12.5% of patients did not receive one upon recurrence. Would the survival gain be present had these patients had access to osimertinib or other TKIs?

Why does it happen?

The main reason for poor post-protocol care is that trials enroll globally, including in countries where post-trial care is limited or absent. This explanation is problematic, raising serious ethical questions.

In our paper, we noted: ”The status quo is unsatisfactory – high-income countries receive data with little external validity, while in low- and middle-income countries, only a small number of participants gain temporary access to the drug and typically lose it when the study ends.”

Rewards: an example in perioperative strategies in bladder cancer

Immunotherapy is standard therapy for patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Logically, when testing these drugs earlier, such as in neo/adjuvant approaches, survival results should rely on ensuring that control-arm patients who recur have optimal access to immunotherapy.

NIAGARA, a global trial, found a large OS benefit for perioperative durvalumab, but according to discussions following the 2024 conference presentation, post-protocol access was likely low and remains unreported to this day.

Conversely, AMBASSADOR, conducted entirely in the US, tested adjuvant pembrolizumab and found improved DFS but not OS. High access to immunotherapy at recurrence may explain the lack of OS gain.

The AMBASSADOR trial, with optimal recurrence care, did not lead to approval. Durvalumab, however, was approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency based on NIAGARA. It is the only perioperative agent with NCCN Category 1 support – despite lacking post-recurrence data, which are likely suboptimal. In our paper, we concluded, “The side-by-side comparison demonstrates how the current system may reward trials with poor post-protocol care.”

Solutions

Regulation is the key: ultimately, sponsors follow the rules. If agencies were to withhold approval from trials that failed to demonstrate that optimal post-protocol care was provided, the current landscape — where post-protocol issues are pervasive — would shift.

We believe that sponsors should be mandated to provide essential post-protocol therapies. Some say companies cannot afford to pay for post-protocol care. Consider again the example of ADAURA : Osimertinib was first approved in 2015, the year the trial was launched. It is difficult to argue that a company with $24.7 billion in revenue at that time could not have provided essential post-protocol therapies to a few hundred trial participants.

Regulators could require prespecified post-protocol care plans aligned with the standard of care in countries where marketing will be sought, ideally agreed upon before trial launch through consultations with agencies. Since the standard of care (including post-protocol) can change during a trial, protocols should include periodic reviews. To decide whether to allow crossover, they should apply a clear methodological framework, such as the one proposed by Alyson Haslam and Vinay Prasad.

Concluding points

Suboptimal post-protocol treatment is pervasive in trials leading to marketing authorizations, both in the advanced and neo/adjuvant settings. It may also be used as a tactic used by sponsors to create, or at least inflate, survival gains. We believe regulation is the key, and agencies should ensure that optimal post-protocol care is provided in trials intended to seek marketing authorization where such care is the standard. If survival matters, it’s time to give post-protocol care the priority it deserves!

Timothée Olivier, MD, is a medical oncologist at Geneva University Hospital. He completed a research program with Vinay Prasad at UCSF and has published several works on clinical trial appraisal and methodology.

Together with researchers who have been working with Vinay Prasad on this topic for years, we recorded a meeting where we discussed definitions, why post-protocol care matters, shared examples, and suggested potential solutions.

The only part about this which does not stink to high heaven, is that the “standard of care” (to which the control arm should always be availed) will often evolve during the course of a trial. That’s not the fault of investigators or sponsors. However, what IS needed, as the author notes, is a clear mechanism to augment the protocol during the study, such that optimal control arm care is provided throughout the study. It is a pathetic excuse to claim some countries can’t provide such care…if that’s the case, don’t include those patients from those countries in the final primary endpoint analysis.

But otherwise, is nobody giving a darn about ICH-GCP research standards? Do these researchers and sponsors not give a hot darn about the wellbeing of the subjects? (You don’t need to answer that, as I wasn’t born yesterday).

I agree with the main point. Regulators have absconded on their fiduciary duty. Companies will clear the regulatory bar that is set for them, and not go 1 micron higher. To believe otherwise is to ignore the entirety of human nature. So it is up to regulators to hold a firm line, and reject studies and applications where the up-to-date standard of care was not provided to control arm patients throughout a study.

Great article! Thanks