Heart Failure in Trials vs Heart Failure in the Average Hospital/Clinic

I was misunderstood on the Internet. Here is my explanation: it has to do with the (minimally disruptive) treatment of patients with heart failure

Adam and I (and Vinay before he worked for the government) spoke often about how to assess and apply studies to patients. We call this evidence-based medicine, and EBM is what separates clinicians from palm readers.

EBM, however, has one huge limitation: evidence generated in trials does not always apply to your patient. We give this a fancy name—external validity, but it is a simple concept.

I feel that many of the key opinion leaders in academic heart failure don’t appreciate the vast differences between patients in their trials and the patients who present with heart failure in community hospitals across our diverse country.

Here is the Tweet that made some people mad:

In our hospital, and likely in yours too, you have hospital employees who track how often patients who are labeled with “heart failure” get something called GDMT—which stands for guideline-directed medical therapy. GDMT includes four drug classes: a renin angiotensin blocker (ACE-I or ARB or ARNI), beta blocker (but only 3 specific ones), a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (spironolactone), and an SGLT2i.

Compliance is supposed to be 100%. Meaning…if you are a good clinician, your patients are all prescribed these drugs. And pronto; the sooner the better. They are, in the words of the Top People, evidence-based practice.

My issue is that, since I have read and studied the seminal trials, I understand who got in those trials. Trials are special, not only for who gets in, but also the trial environment wherein there are nurse navigators making sure patients understand and take their medicines. In rural KY, there are no trial nurse navigators; and many patients don’t have easy access to a big shiny clinic.

Let’s do a couple examples from the trials, then I will show you some data from real world community practice.

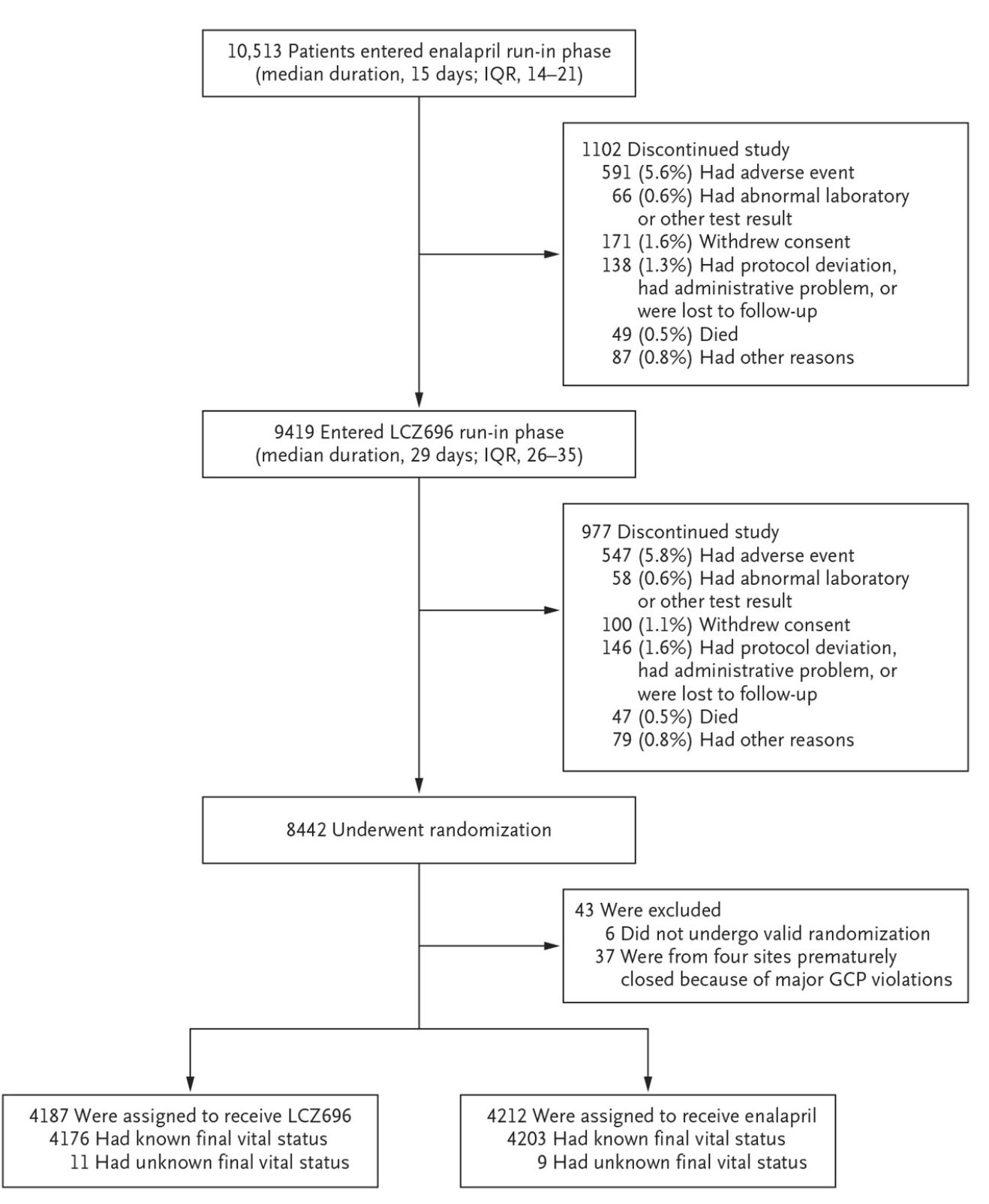

Here is a picture of the “run-in” period for the HF drug sacubitril/valsartan or Entresto.

The trial starts with a two-week period to make sure the patient can take generic enalapril. More than 10% cannot and are excluded. The survivors of enalapril move on to sac/val and another 10%+ drop out. The PARADIGM HF trial famously showed positive results but more than 1 in 5 screened patients were excluded.

Most HF trials have a similar scenario. The carvedilol seminal trial enrolled stable ambulatory outpatients, two-thirds of them had not had a hospitalization in the past year. Yet we are encouraged to start these drugs in fragile in-patients or soon after hospitalization, lest we fail quality measures.

One more issue not faced in trials: cost. The most recent trials find benefit from SGLT2i drugs (though much more modest effects than older trials). So these drugs are part of the GDMT regimen that good quality clinicians adhere too.

But real world patients, unlike trial patients, have to pay for drugs. An 80-year old probably has 8-10 drugs to pay for. And SGLT2i drugs are one of the most costly.

Let’s now be a bit more empirical.

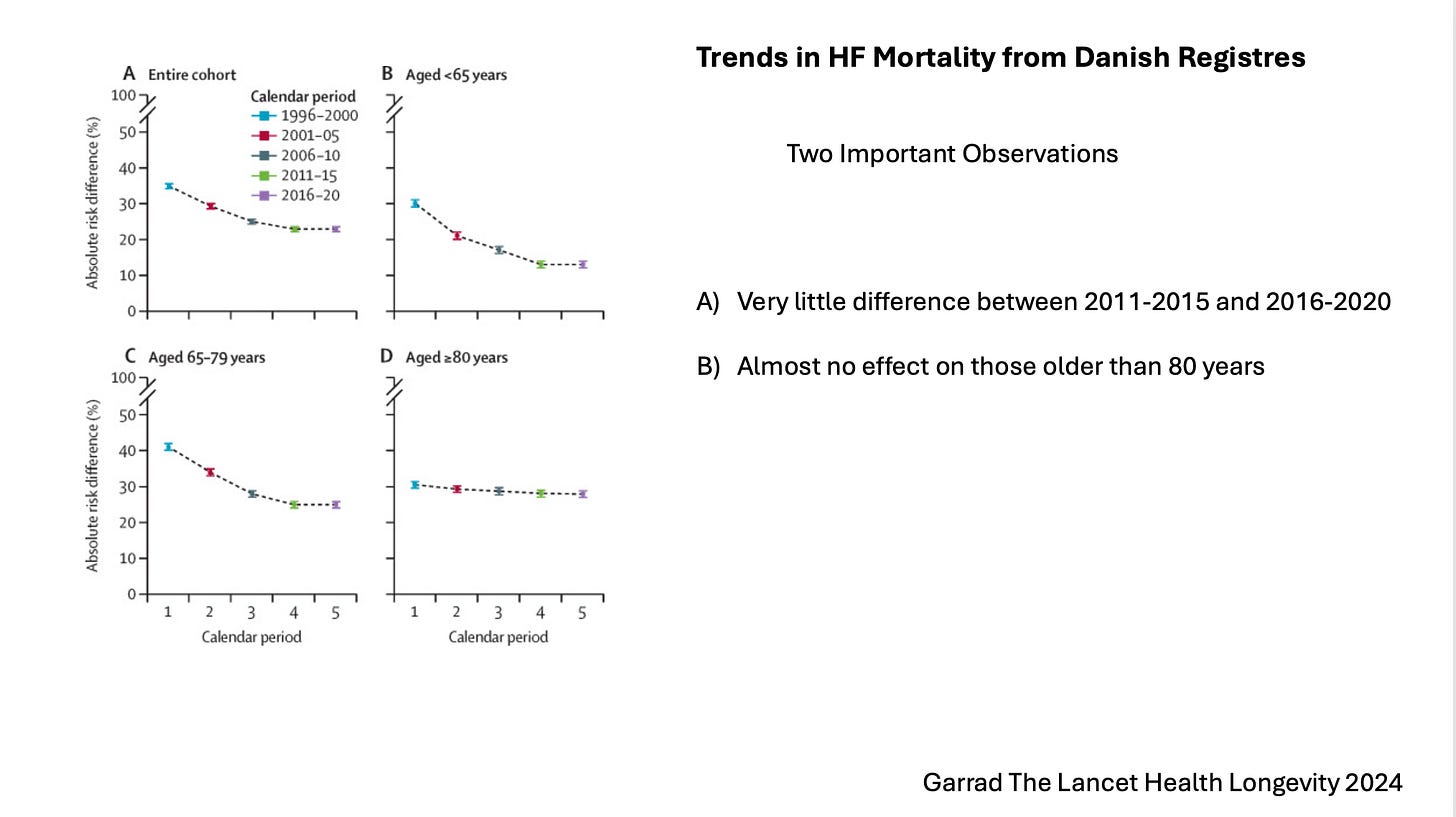

Danish investigators from Copenhagen studied HF mortality trends over the past 25 years. The slide below shows that a) there has not been much decrease in the last 10 years; most of the squeeze came from basic ACE-I drugs. And b) older adults have seen little benefit of advanced HF therapies.

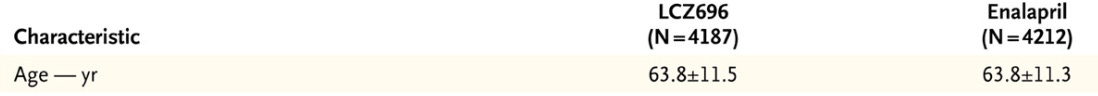

Here is a picture of the ages in patients in the PARADIGM HF trial. I could show you similar pictures from most of the trials underpinning GDMT.

Then there is the matter of frailty.

Frail patients don’t get in trials because they don’t get out of the house much, certainly not to go in for mandated trial visits to the clinic. Frail patients also don’t get in trials because even if they get screened, they likely fall out of the run-in period—for things like low blood pressure or kidney disease.

The same group from Copenhagen used the Danish registry to describe trends in frailty in heart failure.

Here they find that….

The prevalence of frail patients with HF increased from 13.6% to 28.4%.

The 5‐year risk of all‐cause mortality declined across all frailty groups, and frail patients had higher mortality rates than nonfrail patients.

The 5‐year risk of HF hospitalization remained relatively stable across the entire frailty spectrum, as did the risk of non‐HF hospitalization for moderately and severely frail patients.

Neurohormonal blockade was implemented in a uniform pattern in all frailty groups, yet the mortality rate improved more in nonfrail patients relative to frail patients.

Conclusion

We have to do something about the misuse of EBM in heart failure. Yes, when I have a robust 50- or 60-year-old ambulatory patient with severe LV systolic dysfunction, I push hard with medications and devices. It’s a full court press, because the evidence supports this. Everyone agrees.

Yet, an increasing percentage of patients with a heart failure diagnosis have numerous other comorbid conditions that make them unlike patients in the clinical trials. For these patients, aggressive GDMT could be non-beneficial or even harmful.

Yet, on paper, the wisdom to prioritize the most helpful things (like low-dose ACE-I alone or an MRA with a loop diuretic) looks like bad care. But it is not bad care. It is what Dr. Victor Montori calls minimally disruptive care.

The current push to be aggressive with all HF patients belies common sense.

My original post on X was directed at key opinion leaders who (seemingly) under-recognize the complexity of frail older patients who carry the diagnosis of heart failure.

Perhaps it is because 100% of the patients I send to academic advanced heart failure centers are youngish robust patients with isolated LV systolic dysfunction. I don’t send the lady with kyphosis, COPD, CKD and no one at home to help them.

For this common patient, the good clinician finds a way to resist the urge to do too much.

Footnote: See this post from 2023 from Adam: GDMT Bugs Me

Dr Mandrola -- Excellent post! The more is better bias is especially harmful to the elderly frail patient you describe.

I have a minor quibble: The opinion leaders who author the guidelines surely know that real life frequently deviates from trial conditions, but press ahead anyway. After all, they are beholden to their pharma paymasters to hawk their drugs as widely as possible even when a real life patient would have been excluded from the trial.

Spot on. Real world, and Ivory tower are different universes. Studies don’t have to take all comers. Physicians do. Perhaps we should perform large scale trials on all-comers: if you have condition X, and a pulse, you’re eligible.

‘Confounding factors’? Like, reality? They’re not confounding, they’re confirming. If a new regimen works in SPITE of the heterogeneity of humanity, count me a believer. Not unless.