How a Meta-Analysis can Mislead—The Story of Complete vs Culprit-only PCI in STEMI

Andrew Foy provides the Study of the Week--a critical appraisal of an influential but highly flawed meta-analysis.

When a doctor does an angiogram during an ST-elevation MI (STEMI), there is a culprit occlusion but often other partial occlusions.

The question is: should the doctor stent just the culprit obstruction or all the obstructions?

This is a controversial topic in cardiology—not only to sort out the best way to handle STEMI, but more so about how it informs the nature of stable CAD.

Numerous trials have proven that preventive PCI, compared to up-front medical therapy alone, has not been shown to reduce the chance of dying or having a heart attack or dying in patients with stable coronary artery disease.

Now consider the stakes: if complete PCI performs better than culprit only PCI it would question the tenet that revascularization does not help in stable CAD. Perhaps there is something different about stable CAD in patients presenting with an acute infarction? But perhaps there are problems with evidence interpretation.

To address this question, multiple trials have randomized patients with acute STEMI and multivessel disease to complete revascularization (culprit lesion + non-culprit vessels) or culprit lesion only PCI. The results have been inconsistent.

On our recent podcast for Cardiology Trials on Substack, doctors John Mandrola, Mohammed Ruzieh and I discussed 3 clinical trials, which addressed this topic. (PRAMI, COMPLETE and FULL-Revas).

PRAMI was a small trial and underpowered for the endpoints of death or MI. As one might expect, it showed complete vs culprit-only revascularization reduced the need for future procedures. No big surprise. A substantial portion of this reduction in future PCI is likely due to the unblinded nature of the study. PRAMI was too small to say much about death or MI.

The COMPLETE trial was larger than PRAMI and powered for the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or nonfatal MI. It showed a reduction in the primary endpoint for the complete revascularization group, which was driven by reduced MI (5.4% vs 7.9%) while cardiovascular death (2.9% vs 3.2%) and all-cause death were similar (4.8% vs 5.2%).

This was the first large trial to show a benefit on any hard endpoint for preventive PCI in stable CAD; however, I advise caution in accepting these results at face value.Mainly due to nuance surrounding the way investigators defined MI.

In COMPLETE, diagnosis of peri-procedural MI was more difficult to make then it would be in the non-MI setting but it does not mean that such events did not occur. This could account for the difference in events. For instance, in the seminal COURAGE trial, periprocedural MI accounted for 25% of all MI’s. It is also interesting that in COMPLETE, there were no statistically significant increases in safety events in the complete revascularization group despite patients receiving twice as many stents.

The final trial we discussed was FULL-Revasc, which used FFR (a way to judge the severity of the obstruction) to guide complete revascularization compared to culprit vessel only PCI. Theoretically, FFR should improve the outcome of patients receiving preventive PCI by limiting revascularization to hemodynamically significant lesions (FAME trial). (At least this is a common belief among many experts.)

FULL-Revasc planned to enroll a similar number of patients to the COMPLETE trial; however, after results from COMPLETE were published, the investigators stopped the trial early after only about one third of the intended number of patients had been enrolled.

In my opinion, that decision is inexplicable. The charitable explanation would be that they deemed the COMPLETE Trial sufficient enough to eliminate equipoise, and thus they felt it would be unethical to continue randomizing patients. An uncharitable view would be that they wanted a positive result and didn’t want to risk undermining it with the results of their own trial, which was heading in a negative direction.

Unlike COMPLETE, in FULL-Revasc there was no significant difference in the composite endpoint or any individual components of it including all-cause death (9.9% vs 9.3%) or future MI (8.0% vs 7.5%), which were both numerically higher in the complete revascularization arm. Notable was that FULL-Revasc had higher event rates than COMPLETE.

Doctors Mandrola, Ruzieh and I feel the evidence is insufficient at this time to recommend routine preventive PCI in patients with STEMI and multivessel disease. At least 5 professional medical societies disagree—due in large part because of a “positive” meta-analysis by Reddy et al.

How Can a Meta-Analysis Deliver Positive Results from Not So Positive Individual Trials?

The authors report that complete revascularization following acute MI significantly reduced all-cause death and cardiovascular death as well as MI. That is a surprise because we just reviewed 3 major trials and none showed a significant difference in death.

The forest plot for the outcome of all-cause mortality is shown below.

Combining Dissimilar Studies

The summary effect is displayed by the red diamond at the bottom. It shows the that relative risk of death for patients randomized to complete revascularization compared to culprit revascularization is 0.85 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.74 to 0.99 and thus, meets statistical significance. This is odd considering two of three trials contributing the most weight to this analysis are squarely negative for mortality (an easy way to spot trials that contribute more weight to a meta-analysis is to look for those with narrow confidence intervals; red triangles).

But there is a third trial contributing a lot of weight, indicated by the black arrow, which is the FIRE trial. We did not review it on CardiologyTrials—for several reasons. Mainly because FIRE studied a mixed population of patients with STEMI and NTEMI.

NSTEMI is much different condition than STEMI. For instance, one reason for performing complete revascularization in NSTEMI is that the culprit lesion is often unclear. Our team studied this nearly a decade ago. We showed that experienced interventional cardiologists struggled to identify the culprit vessel in NSTEMI. The same is not true for STEMI where the culprit vessel is easy to identify.

Including dissimilar trials is one of the biggest problems in meta-analyses.

The FIRE trial presents another concern. That is: it has an outsized treatment effect– a 30% reduction in death! This could be due to chance alone, bias in the study design, or nefarious actions on the part of the investigators.

To make sure a meta-analysis is not being driven by outliers, investigators are encouraged to perform sensitivity analyses. One type of sensitivity analysis involves repeating the analysis with exclusion of individual trials. The Reddy meta-analysis includes 15 studies for the outcome of death so there should be 15 different sensitivity analyses with a single study excluded each time. (Easy to do with software).

If any of these analyses change the overall result, it reduces confidence in the summary effect and conclusions. Reddy et al. did not perform all such an analyses. However, they do present data from a sensitivity analysis that included only trials of patients with STEMI. Shown below:

The only trial not included in this analysis is the FIRE trial and the summary effect is no longer positive. Compared to the overall analysis, the RR increased from 0.85 to 0.91 and the upper bound of the 95% CI exceeds 1 and no longer meets statistical significance. Also problematic is that the mild amount of heterogeneity in the first analysis, as indicated by the I2 value of 7.1% went to 0%, supporting the fact that the FIRE trial is indeed an outlier that drove the result.

The analysis excluding FIRE should have reduced authors’ confidence in making conclusions about complete revascularization. But it didn’t. Instead, the authors suggested the results in STEMI-only patients were not that different from the combined analysis with STEMI and NSTEMI patients and doubled down on the recommendation to adopt the practice in both populations!

Small Study Effect

Yet there are additional problems: As you can see in the above analysis, there are really only 2 trials that provide a lot of weight to this analysis. They are the COMPLETE and FULL-Revasc trials, indicated by the red triangle and narrow confidence intervals relative to the width of the confidence intervals of the other trials.

Both these trials are both squarely negative and one can imagine that if these 2 were combined, the summary results would be close to 1 with the upper and lower bound of the 95% CI being about the same. This means that the summary effect from this analysis of STEMI only patients is being pulled closer toward a positive result due to the effect of small studies.

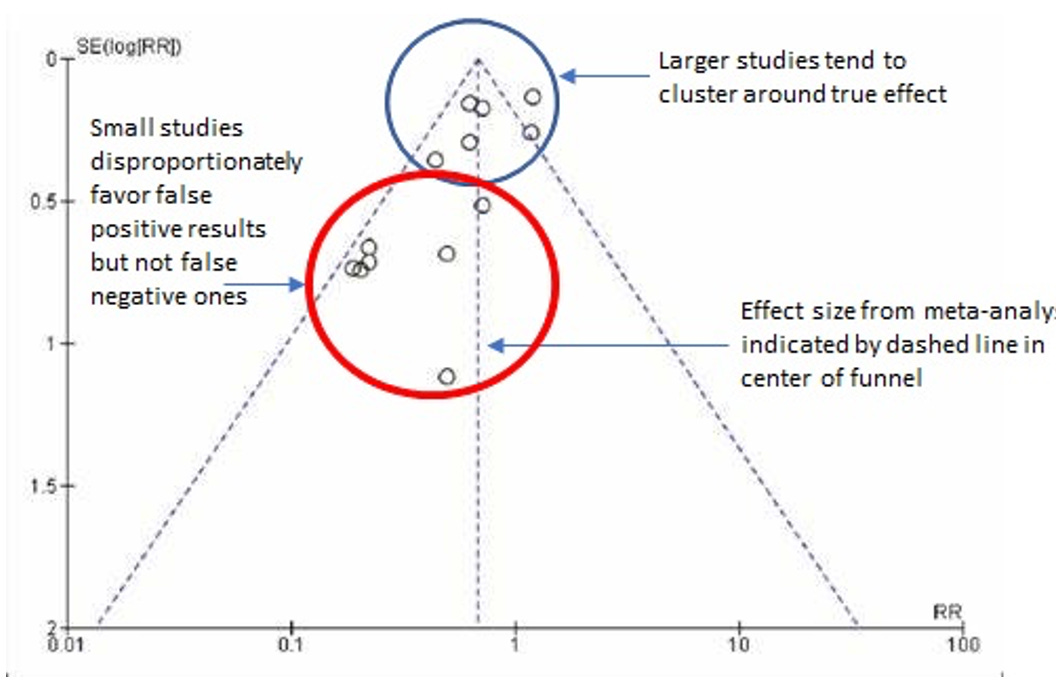

When trials are small, and underpowered for the endpoints of interest, they produce wide confidence intervals and are likely to yield both false positive and negative results. But it is the false positive ones that tend to be published – a phenomenon called publication bias. This is a widely known problem and there are statistical techniques to assess it. The authors did not present these analyses.

I made this example of what a theoretical analysis would look like if the results were disproportionately affected by small studies with publication bias.

Without a funnel plot we can perform our own type of stress test for small study effects on the Reddy results by looking at the Forest plot below and counting the number of small studies with extreme positive results, which is 7 (blue boxes) and those with extreme negative results, which is 2 (black boxes). Three trials don’t favor one or the other and the remaining 2 trials are the large ones indicated by red triangles.

Without applying any statistical test, we can make an educated guess that small study effects from publication bias are present in the Reddy analysis and this should further undermine confidence in the results.

Selective Inclusion Choices

There is yet is another red flag to accepting the conclusions from the Reddy analysis - the studies were cherry picked. How can this be? The words “systematic review” are highlighted in the title.

In the Introduction the authors explicitly state,

We performed an updated systematic review and network meta-analysis including the totality of randomized data investigating revascularization strategies in patients presenting with MI and multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD).

It is strange, therefore, that they would leave out a prominent trial, CULPRIT-SHOCK, published in 2017, involving 706 patients with 325 deaths. Compared to complete revascularization, culprit only PCI significantly reduced the chance of dying (43% vs 52%; RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.72-0.98; p=0.03). The inclusion of this trial in the Reddy analysis would have completely changed the results.

It is not until the 3rd subsection of the methods where the authors write,

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they randomized patients presenting with MI who had multivessel CAD after successful culprit artery PCI. Trials of cardiogenic shock were excluded.

That is it. They do not say why.

One would think that such a significant aspect of the inclusion/exclusion criteria would at least merit some mention in the title or introduction. A proper title of this meta-analysis might be “Percutaneous Coronary Revascularization Strategies in Stable Patients After Myocardial Infarction.”

Why is this so important? Mainly, because a trial like CULPRIT-SHOCK fulfills the basic inclusion criteria of the review and there is no obvious reason why, if preventive PCI works in MI patients, it should not work for those in cardiogenic shock. At the time the trial was undertaken, there were experts who argued it should be done to improve overall myocardial perfusion and function. There were also those who disagreed, citing safety concerns.

From my standpoint, it is not surprising that a procedure-based intervention with risks and benefits can have an overall benefit in some patients, particularly those in better clinical condition, but can cause overall harm in those who are more fragile. In fact, this is a core tenet of treatment effect heterogeneity and patients in cardiogenic shock represent a particularly high-risk patient population.

The Challenge of Acknowledging Treatment Effect Heterogeneity

There needs to be good reasons why the intervention is successful in some and bad in others. Acknowledgement of this tends to dampen enthusiasm for clinical adoption, which is why, in my opinion, there are so few trials that target high-risk patients.

For the Reddy analysis, the reasons for exclusion of patients with cardiogenic shock are unclear. A cynic would say it was because it’s inclusion would make it impossible to demonstrate a benefit for preventive PCI.

Summary

The Reddy meta-analysis is used to support guideline-based recommendations for preventive PCI in patients with MI and multivessel disease.

Yet, based on these issues, I believe, and hoped to have convinced you, that the evidence is not strong enough to support a routine strategy of preventive PCI in patients with STEMI and multi-vessel disease. There may be a benefit for complete revascularization in NSTEMI patients, but more evidence is needed.

For independent review of cardiology trials I invite readers to follow or subscribe to the Cardiology Trials Substack.

Editor’s Note: The most important aspect of this appraisal extends well beyond one specific clinical question in cardiology. The vast majority of readers are not interventional cardiologists.

The importance of this appraisal—from one of the best thinkers in medicine—is that it demonstrates the complexity of interpreting medical evidence, and how it can be easily slanted in favor of one strategy.

While this post is technical we love that Sensible Medicine gives these arguments a public voice—one rarely seen in traditional medical journals.

Please consider supporting our work. JMM

A suggestion: “Numerous trials have proven that preventive PCI…” This would better read: “Numerous trials strongly support that preventive PCI…”

My reasoning is that the words ‘prove’, ‘proven’, ‘proved’ only rarely (if ever) can be prudently used in writing about scientific research.

As Dr Foy analyzes so thoroughly in this essay, the 'Do more' bias is strongly evident. This phenomenon is pervasive across medicine. I'd bet that the five cardiology societies pushing for the broader intervention have an economic conflict of interest, either by funding from device makers, or just higher fees when they perform the more extensive PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) rather than the more conservative intervention.