How Good is the Apple Watch at Detecting Hypertension?

And how will the function impact doctors and patients?

I hate to overstate the importance of a Sensible Medicine post, but the study reported on here by Caspian Kuma Folmsbee will affect many readers — doctors, Apple Watch wearers, both — in the coming months. I love a good test characteristics study. I love thinking about the impact of introducing health care technology to an unsuspecting population. This article comments on both.

Adam Cifu

In September 2025, Apple released a new health feature: hypertension alert. Hypertension notifications are “powered by a machine learning–based algorithm to identify key photoplethysmography (PPG) patterns that may indicate hypertension. The algorithm uses 60-second segments of PPG signals as inputs, collected approximately every two hours throughout nonoverlapping 30-day evaluation windows.”1

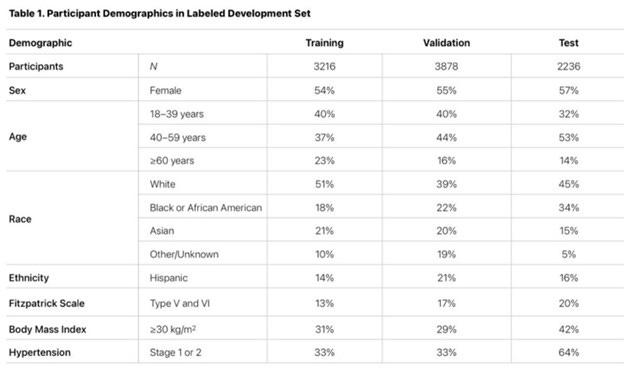

With the update, Apple released a validation study that defined the test characteristics – sensitivity and specificity – of the function. The study compared the algorithm noted above to the gold standard of average blood pressure readings taken twice daily at home over 30 days. Participants were instructed to wear the watch 12 hours a day. Apple used 3216 participants to train the data, 3878 to validate it, and then 2236 participants to test it.

Table 1 below has the demographic details of the participants. About 40% were aged 18-39, 50% were white, and 20% were Asian. The training set was 18% African American, with the test group being 34% African American. 33% of the training group had Stage 1 or 2 hypertension. 64% of the test group was hypertensive. It is unclear how they decided to assign participants to their respective groups.

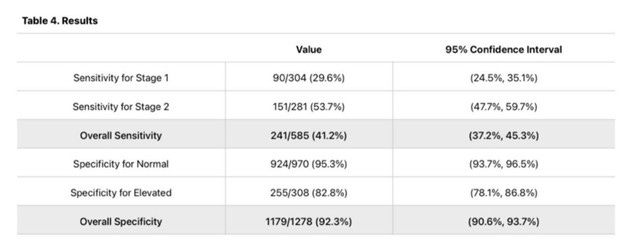

Using blood pressure measurements as the gold standard and the training sets, the study calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm for detecting hypertension. (Table 4 below).

As a reminder, sensitivity is the ability to detect disease. If there were 100 patients with hypertension, the sensitivity would be the proportion correctly identified as having hypertension. Specificity is the proportion of people without disease correctly identified as not having disease.

As you can see, the overall sensitivity is 41% for Stage 1 and 2 hypertension. The specificity was 92%. So out of 100 theoretical patients with hypertension, we would correctly identify 41 with hypertension, and the remaining 59 would not be notified. 8 out of 100 theoretically healthy (normotensive) patients would be falsely alerted that they are hypertensive.

Unfortunately, a true appraisal of this study is impossible since it is not a typical academic publication. The document lacks details about the methodology. For example, where did they get these participants? Are they employed? What is their income? Did they have HTN already? Were they already getting treatment for other medical issues? This information is critical to determine the external validity/generalizability of these test characteristics.

Furthermore, how often were people actually checking blood pressure, and were they doing it correctly? Did participants really do it twice a day as specified in the protocol? We know the type of machine they were using, but blood pressure evaluation is not a simple procedure. Were patients blinded to the watch notification? Did they seek out medical care?

There are no answers to these questions, and I wonder if it is right to roll out a feature to millions of people based on a study with only a couple of thousand people. Perhaps there were other validation studies, but this one is pulled directly from the Apple website and presumably the most robust.

But here is my takeaway about these internal validity concerns – It does not matter.

It does not matter if the sensitivity is 20%, 40%, or even 80%.

It does not matter if the specificity is 85%, 90%, or even 95%.

Before I explain, it can be helpful to work through a theoretical example with the results.

Apple was projected to sell 55 million Apple Watches in 2025. Let’s say that projection is more like 20 million, and let’s assume that only half of those will use the hypertension notification feature. Let’s assume 10 million people use this feature and assume a prevalence of hypertension of 20%. (In underserved Chicago neighborhoods, that rate is as high as 50%). Of the 2 million who have undiagnosed hypertension in that group, assuming a sensitivity of 41%, 820,000 will get notified that they might have hypertension. That leaves 1,180,000 with hypertension who were not notified.

Assuming a specificity of 92%, of the remaining 8 million (80%) without hypertension, 640,000 (8% x 8,000,000) will be falsely notified of high blood pressure. The classic point to make is that even with a “good” specificity of 92%, 640,000 is a lot of false positives. The positive predictive value in this case would be 56%, or put another way, if someone was notified by their watch of potential hypertension, they would have a 56% chance of truly having hypertension.

Now repeat the above with worse sensitivity, or maybe better specificity. The numbers change, maybe by a couple of hundred thousand in each group.

But here is my point – it does not matter.

Does a watch notification make it easier for a person to see their primary care doctor? A person who got the notification will also have to compete with appointments with the 1,460,000 others who were also notified, 640,000 of whom do not have hypertension but were told they might.

Flooding these patients into an already overwhelmed primary care system is not in the best interests of public health.

Primary care needs to get out of the preventive care business or at least deprioritize it. We need to focus on those who need our help, such as those with multimorbid comorbidities who are acutely ill and cannot get appointments for months.

If we really want to tackle the real problem of cardiovascular disease, it will take more than a watch notification.

Caspian Kuma Folmsbee is a primary care provider in Chicago. He publishes at Kuma’s Substack.

I've had the thought recently: If you could have a full body monitor/scanner/tester that was constantly evaluating the state of your entire body, would you want such a device? Would such a device be "healthy" for you? I think certainly not. Constantly fretting over every little variation or deviation from mean would not make a happy, full, well-lived life.

Dr. Folmsbee,

Regarding your interesting comment on the usefulness of the Apple Watch for the detection of hypertension, in our department we have taught that there are at least five aspects to consider when deciding whether to use a diagnostic test. Four of them go well beyond its operational performance (sensitivity, specificity, overall accuracy, Youden index, post-test diagnostic probabilities, even the number needed to test for a true positive or a false negative, and the diagnostic help-to-harm ratio).

It is worth noting that the detection of hypertension using the Apple Watch shows a very modest overall diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) of 10.6; in other words, it is a diagnostically weak test.

The first of these additional aspects is the user’s pre-test probability of hypertension. Assuming some hypothetical validity of hypertension detection by Apple Watch PPG, and given its relatively higher specificity, such a tool would be indicated not as a screening test, but rather as a confirmatory test—used in the clinic or in a primary care setting, not in the community.

The second aspect concerns ease of use, immediacy, intrinsic safety, comfort, innocuous, costless. From this perspective, the Apple Watch would be close to an ideal test for detecting hypertension. We should not forget that there is a growing group of patients with sympathetic hypertonia associated with metabolic syndrome (highly prevalent in the USA) who develop induced “hypertension” (false positives) simply due to the pressure exerted by the sphygmomanometer cuff during measurement—a phenomenon that years ago we referred to as “white-coat hypertension.” Because the Apple Watch sensor is imperceptible, this particular source of error would likely be eliminated.

However, the third—and perhaps most important—element to consider is whether the use of the Apple Watch hypertension sensor would alter the natural history of the risks inherent in so-called “chronic and pathological esencial” arterial hypertension. This question may ultimately be impossible to answer, because medicine continues to suffer from a profound ignorance and conceptual distortion regarding hypertension itself: is it a sign, a symptom, a risk factor, a prognostic marker, an abnormality, a disease, an illness?

In practice, hypertension is instead defined as a pair of numbers—120/80—applied normatively and universally (why could 123/77 or 125/81 not be normal for a given individual?), which have been arbitrarily established using risk-based criteria (because those risks do indeed decrease modestly when such numbers are controlled). Consequently, clinical management becomes centered almost exclusively on prescribing one or more “antihypertensive” drugs, titrated according to those numerical targets.

But what if essential hypertension is, in fact, a homeostatic sympathetic response to mitochondrial distress caused by hypoperfusion secondary to an underlying endotheliometabolic disease that continues to progress unchecked within the organism? In that case, what would truly be the value of having “controlled hypertension”?

A warm embrace,