How Strong is the Evidence for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke?

Consider this a trigger warning. I will tell this story over the coming weeks. I warn you now. You cannot unsee what I will show you.

If you present with symptoms of a stroke, an emergency medicine doctor will rush you into a CT scan. If there is no bleeding in the brain, you will be given a thrombolytic (clot-busting) drug. Few treatments in medicine are more strongly accepted than thrombolytic therapy in the treatment of acute stroke.

I hesitate to even show you the seminal trials. Because questioning this practice is not welcome in mainstream neurology. Yet I will do it anyway. It is a whopper of a story.

NINDs Trial 1995

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDs) trial established the practice of lytic therapy (tPA) for acute stroke. This was a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial of patients with acute stroke—tPA vs placebo.

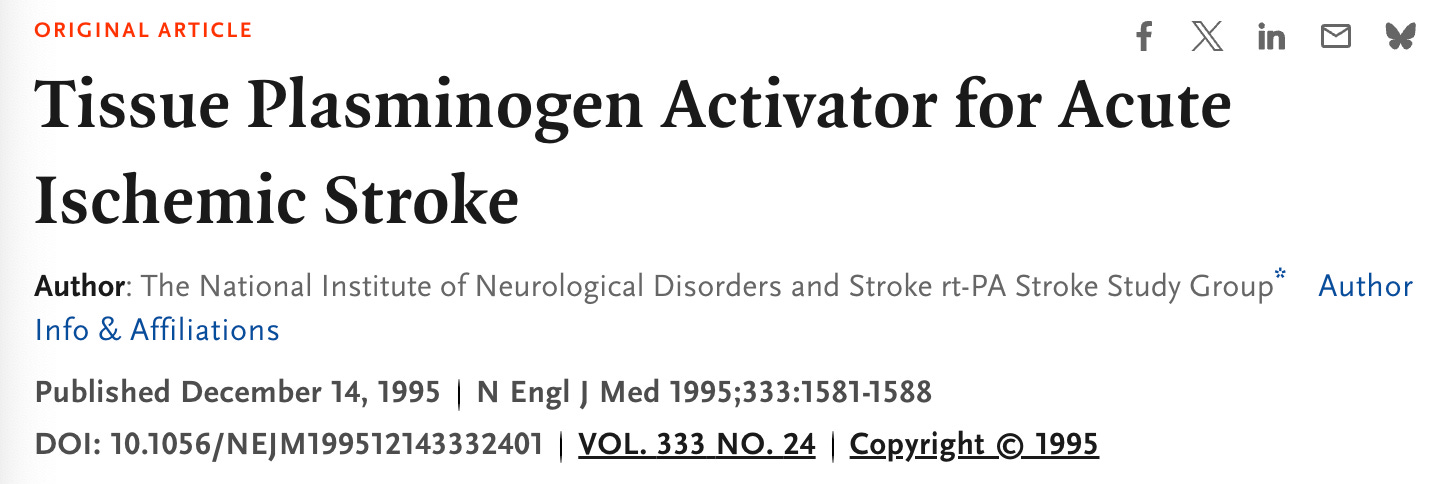

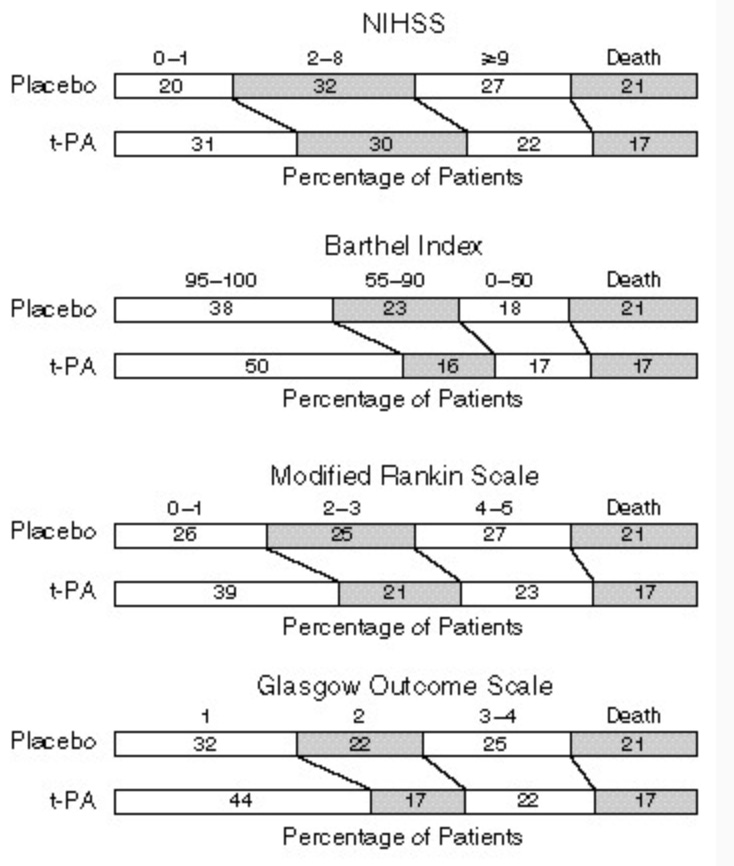

NINDs had a Part 1 and 2. Part 1 enrolled 291 patients to tPA or placebo. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who had improvement in the NIHSS scale 24 hours after the onset of the stroke.

The picture shows the non-significant results.

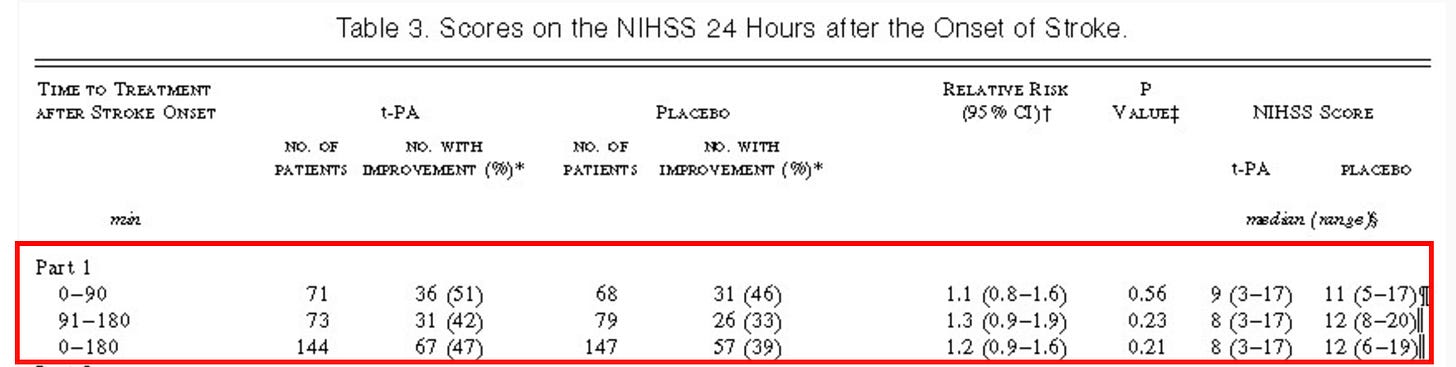

Part 2 was identical in trial procedures, but the authors chose a more comprehensive endpoint of a global statistic simultaneously testing for effect in four stroke outcome measures at three months. (It turns out that there are multiple scales to estimate function after a stroke.) In this part, 333 patients were enrolled.

As evaluated by the global test statistic, the odds ratio for a favorable outcome in the t-PA group was 1.7 (95 percent confidence interval, 1.2 to 2.6; P = 0.008). There were also absolute risk reductions in the number of patients who had minimal to no disability in different stroke scales (12% increase in those with 95-100 on Barthel index for instance).

Below is graphical display of how (part 2) patients ended up in 3 months in the different stroke outcomes. More patients end up in the better functioning category at the left side in the tPA arm.

“The inclusion of variables that differed between the two groups at baseline (aspirin use, weight, and age) as covariates in addition to the clinical center and time to treatment after the onset of stroke in the global test increased the odds ratio to 2.0 (95 percent confidence interval, 1.3 to 3.1).” This is where the take-home message that patients treated with tPA were at least 30% more likely to have minimal or no disability vs placebo.

There were similar trends for the combined analysis. Again in the red rectangle.

There were no differences in mortality at 90 days. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was much higher in the tPA arm—20 vs 2 in the tPA vs placebo arm.

The authors concluded that

Despite an increased incidence of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, treatment with intravenous t-PA within three hours of the onset of ischemic stroke improved clinical outcome at three months.

And there you have it. NINDs launched thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke. It is the core of stroke neurology. It began the process of having stroke centers. So established is this practice, that doctors have been sued for not giving tPA or not giving it fast enough.

The Criticisms of NINDs

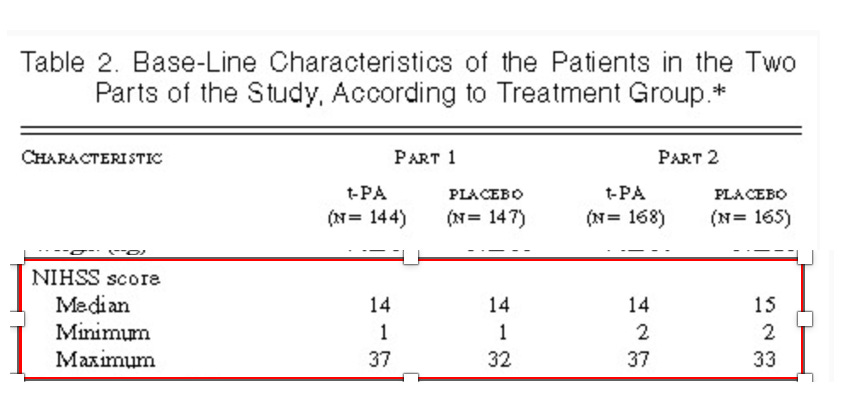

The first and perhaps biggest criticism with NINDs were baseline differences in the two arms. You would never have known this from the initial trial report. Here is the picture from the 1995 paper. They look similar, right?

Well, the authors of NINDs published 5 years later, a paper looking at the effect of early treatment with tPA. Indeed the odds of good outcomes were slightly higher in the early treatment (less than 90 minutes).

In this paper, they also published granular details of the baseline characteristics of the stroke severity in the main trial. There were substantial differences favoring tPA.

For example, within the subgroup of patients treated between 91 and 180 minutes, 19% of those given tPA had NIHSS scores of 0 to 5 (mild) compared with only 4.2% of the placebo group.

In addition, fewer patients in the tPA subgroup had severe strokes (18% vs 27% with NIHSS score > 20).

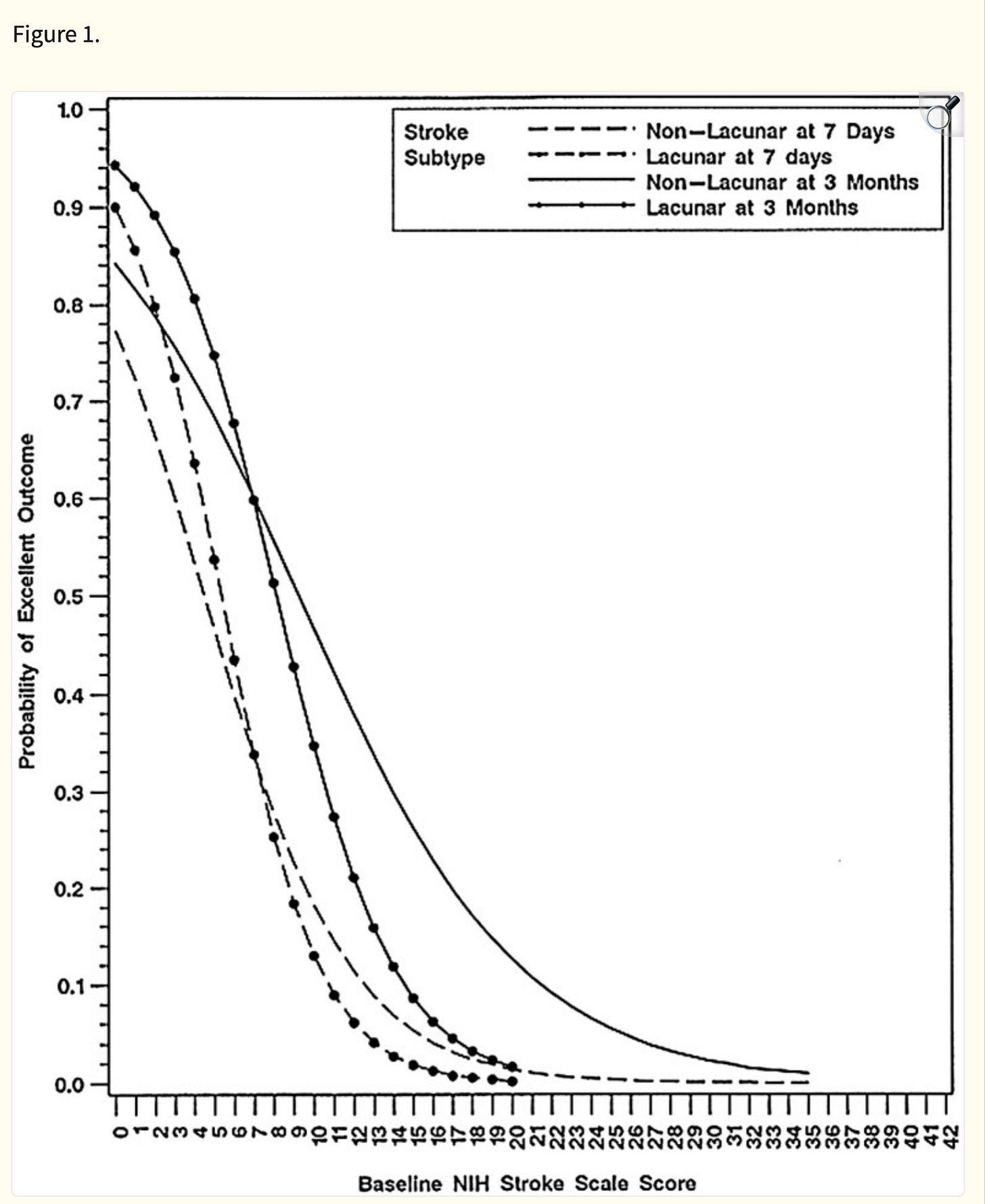

This is huge because the outcome of stroke depends greatly on the severity of the initial presentation, these imbalances bias the results in favor of tPA. Here is a graph showing how steep the curve of probability is based on baseline NIHSS score at baseline.

Baseline differences in NINDs led two independent clinical scientists Jerome Hoffman and David Sprigler to reanalyze NINDs data, which was possible because NINDs was government sponsored.

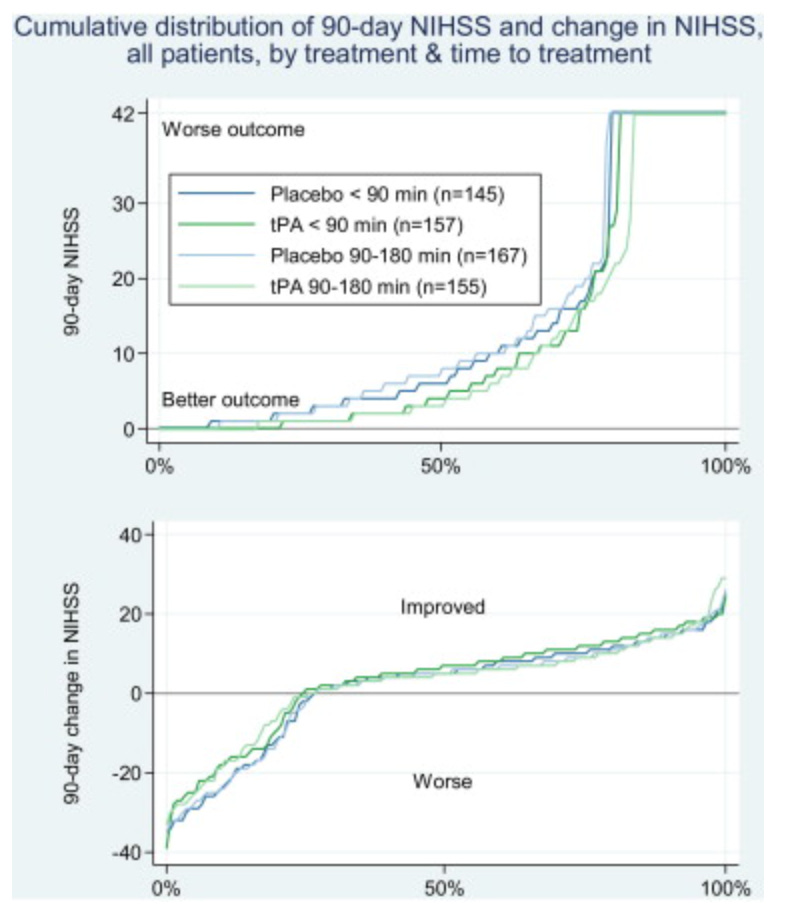

They did a graphical reanalysis of each patient in NINDs.

The basic idea was to graph out what happened to all 624 patients from baseline to 90 days. This allowed them to look at the change in NIHSS relative to where a patient started.

The second part of the graph below shows the change in NIHSS. You can see almost no difference. I have oversimplified this analysis. It’s worth reading on its own.

This unique analysis has been rebutted. NINDs has also been reanalyzed by others, and main results were upheld.

I will inject my opinion here. While many (perhaps most) neurologists side with the original NINDs finding, I find the baseline differences and graphical reanalysis compelling. The small to no differences comport well with the statistical fragility of NINDs. For instance, the Fragility Index of the main NINDs paper is only 3. Had 3 patients been adjudicated in a different category of (subjective) function, NINDs would not have reached its statistical threshold.

The final chapter of NINDs comes from neurologist Ravi Garg. More than 20 years after NINDs, he and another colleague reanalyzed NINDs looking for the reason for baseline differences in stroke severity in the two groups. There are only two possibilities. One is by chance alone, and the other is a problem with randomization.

Their paper strongly suggests there was selection bias in randomization. AKA: randomization errors. It’s open access and worth a read.

And, similar to Hoffman and Sprigler, when Garg reanalyzed the results based on these baseline differences, the benefit of tPA diminished.

Conclusion:

I am sorry to have shown you this. I wish it were not so. I come at this topic as a Neutral Martian. I am not a neurologist. But i find this a compelling story. The seminal trials of thrombolytic therapy for acute MI are not like this; they were compelling. But the brain is different.

You might ask about other trials. Indeed there were other lytic trials in acute stroke. Here’s a teaser for next week: all but one trial have been either null or stopped for futility/harm from tPA. The one other positive trial, ECASS III, has also been reanalyzed and the results challenged.

Stay tuned for next week. And always read seminal trials. It’s not just a historical exercise.

And remember that Sensible Medicine is reader supported. So please do subscribe.

I followed Jerome Hoffman’s analysis as a paid subscriber to one of his publications for many years. He also was an early debunker of the ADA promulgated idea that everyone’s hemoglobin A1c needed to be as low as possible, which was subsequently borne out by multiple trials showing net harm with very aggressive glycemic control efforts.

However, although I thought his criticisms of the thrombolytic treatments for stroke were very well reasoned, as you mention in your post, thrombolytic treatment for stroke has spread widely, and it’s considered heresy to challenge it. In my opinion, part of the reason for that is financial. Hospitals advertise these “stroke centers” and anyone who comes in with any neurological symptoms at all, even if non localizing and extremely unlikely to be stroke, gets at least 3-4 advanced imaging studies and there is a very low threshold for giving thrombolytics and putting someone in the ICU. I’ve seen thrombolytics given for slurred speech in people who were objectively intoxicated with alcohol based on blood test results. And when people return repeatedly with vague neurologic symptoms, the same workup is repeated over and over.

This is a huge money maker for hospitals and others. It’s also often a terrible use of resources and can be dangerous.

I am not a neurologist and not research-minded, but a practicing ER doc for >30 yrs. I have practiced through the entire TPA era. ER docs were the first to seriously question over and over again the utility and efficacy of thrombolytics in ischemic strokes. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical dollars have captured and hold captive the C-suites who make the decisions of clinical practice, not the doctors on the ground like us. That train left the station long ago, and even an entire specialty (EM) couldn't stop it. Every stroke patient is unique and a "fight" to do the right thing. I've disagreed openly with neurologists, and yet they still give the lytic. There is so much spin, and the public just buys it. The neurologist tells us there are more lawsuits for NOT giving the lytic than for withholding it. To intimidate us EPs into giving lytics? To follow blindly the standard of care of the local community? To do what the C-suite has established as standard of care?? I rejoice when I find a contraindication to lytic therapy.