"I just want to work on my car"

Screening for lung cancer often forgets the patient entirely

I always tell junior faculty that your contract means little, and, indeed, I found that to be the case, when a mid-career faculty departed and I inherited a third of his lung cancer patients. Yet, like most unexpected clinical changes in my career, I ended up learning unexpected truths.

One man taught me about lung cancer screening.

He was the most improbable 74 year old. He was thin— rail thin— partly because he was a smoker. He wasn’t an ordinary smoker. He had smoked 3-4 packs a day for most of his life; He had somewhere between 100 and 200 pack years of smoking, and age had not slowed him. He still enjoyed cigarettes from the first moment in the morning to the last puff before falling asleep in bed.

He lived alone, and worked on old cars in his garage. His fingers stained with nicotine and grease. When I asked him who was closest to him— he said no one. He never had kids. When I asked him what he enjoys doing, he said working on his cars. When I asked him how his health was, he replied flatly. “It’s fine— I never had a problem till I met those doctors.”

Of course, the medical industrial complex didn’t leave him alone; Instead, they sunk their teeth into him. A few years before, on a routine visit, they drew a a large battery of blood tests, and recommended colonoscopy. After learning what a colonoscopy entailed, he never had it done.

His doctor also referred him to a lung cancer screening program. Because this was a non-invasive test (a CT scan), he went ahead with it. And that was the last time he was in good health.

There were several concerning spots on his CT scan and in the years that followed a few were treated. He had a needle biopsy of three, and one revealed an adenocarcinoma. After PETCT and EBUS, he underwent a resection, and received adjuvant chemotherapy. A year or so later, another nodule grew suspiciously. This time biopsy found small cell lung cancer. He underwent surgery, radiotherapy, and again got a course of chemotherapy. When he entered my care, yet a third nodule was growing, biopsy showed squamous cell cancer. He underwent resected, and our tumor board was discussing adjuvant chemotherapy.

Of course, there were no data to support another course of chemotherapy— we had passed any data driven decision long ago. I didn’t think we should even offer it.

But he is really high risk, one doctor pressed.

“The question isn’t whether he is at high risk, it is whether the net effect of more chemotherapy is beneficial. We have no data to support the idea it is, and I truly doubt that is the case,” I argued.

Like most disputes, we decided to take it to the patient to settle. Naturally, the patient sided with me.

I’ve already done this twice. I was fine before that scan. I have never felt bad in my life— except for what you doctors did to me.

And what had we done to him? We took this man— who just wanted to work on cars — and extolled him to undergo CT screening for lung cancer. We did that because one trial, NLST, showed a benefit on lung cancer specific and all cause mortality years ago.

But that trial had flaws.

The control arm wasn’t the standard of care at the time— but an unproven intervention of chest radiography. Naturally, this would mask the harms of screening. Moreover, the gains in overall mortality exceeded gains in lung cancer mortality— a recipe that stinks of statistical noise. In fact, that view was vindicated a few years later, as the all cause mortality benefit vanished in follow up. These arguments are detailed in this paper I cowrote. NLST, thus, failed to justify lung cancer screening programs.

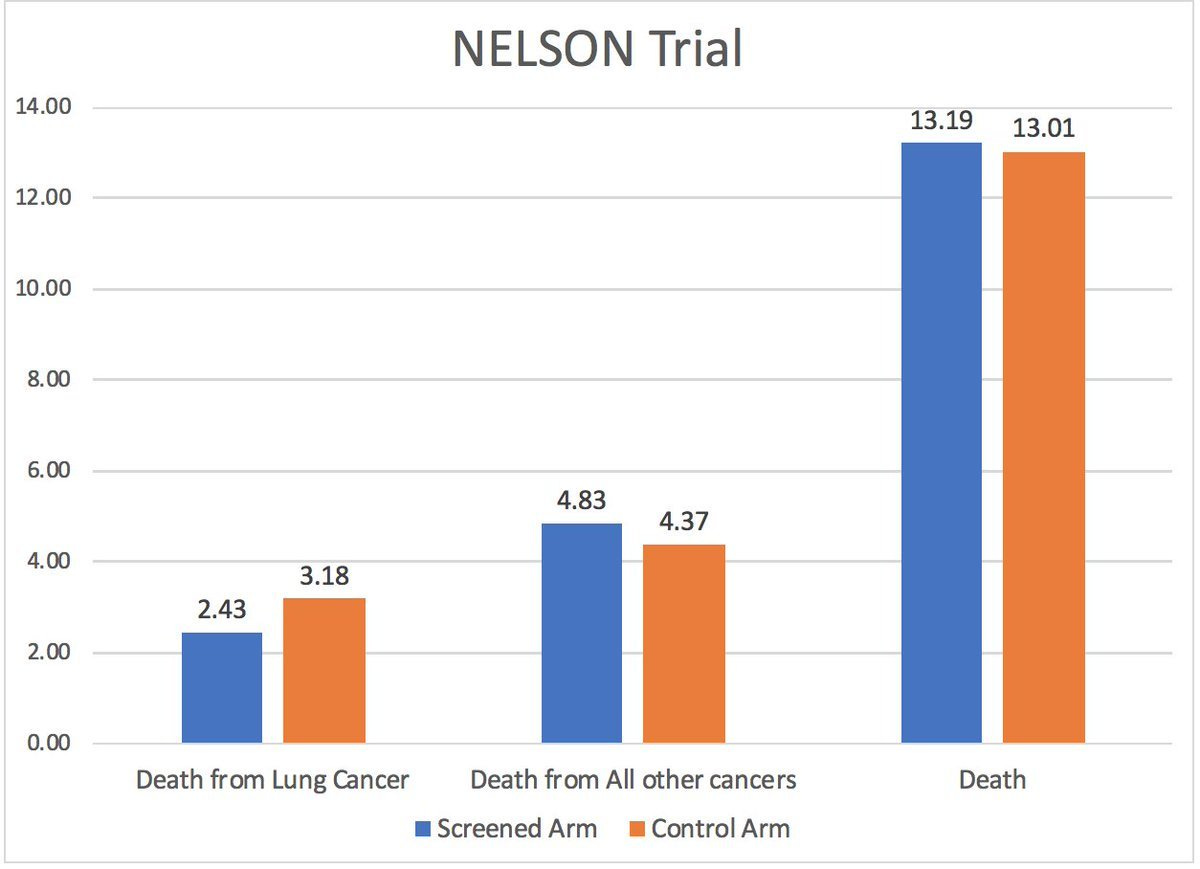

Then we have the NELSON trial— another study that claims lung cancer screening ‘saves lives’. But here is the central result:

Whatever gain in death from lung cancer, appears to mean nothing when viewed against dying for any reason. People want to live longer— not just swap causes of death. The NELSON trial cannot disambiguate these two scenarios.

Meanwhile, my patient wants to keep smoking 4 packs a day and just wants to work on his cars. I asked him bluntly if he felt lung cancer screening was worth it.

What do I know? They just told me where to show up for the scan. I assumed they knew what they were doing. I never felt bad until they started on me.

I asked him what his goals in life were.

I don’t care how long I live. I just want to spend whatever time I have doing what I want.

It couldn’t be clearer to me. Had this man been properly counseled, he would likely have declined screening.

Some might say that had it not been for screening, he would be dead already. That is something an inexperienced and arrogant doctor would think because an experienced and humble doctor would know that we have no idea what the counterfactual would be.

The lead time bias from CT screening programs may be so considerable for some lesions— the illusion of life saved could exceed actual lives saved by many order of magnitude. The truth is— when randomized data do not show overall survival benefits— you have no basis to think you are saving lives. You aren’t better than any other charlatan.

Next, some would say: yes we should give him more chemotherapy. I would argue that those people are off their rocker. He already got at least 1 course of chemotherapy that completely lacked data (adjuvant for v. early stage small cell AFTER prior platinum based adjuvant for pulmonary adenocarcinoma). His whole treatment course is unproven. Perhaps the chemo is just treating the malpractice lawyers rather than the patient in front of you.

Who do I blame for all this?

When I think about this man, I get frustrated with the ‘experts’ who advise lung cancer screening. Many have built centers devoted to such efforts, or run multi-million dollar grants to increase utilization. Do they not see the glaring conflict of interest?

More screening means more patients and more business. More screening means those patients are in your care for longer, even if they don’t live longer. More grants helps build your reputation and secures your career.

But perhaps for just one moment, can you actually think about whether you are helping anyone?

And yet, such experts are incredibly hostile to such considerations. Their worldview hinges on the fact that the program must be good— ergo, their life’s work must be in pursuit of the good. It’s motivated reasoning at its worst.

Meanwhile, my patient

Smoking cigarettes while working on your car is such a simple pleasure. When you are 74 and that’s what brings you joy— and you do it knowing you might be shortening your life— who are we in medicine to object?

Then preventive medicine approaches this man with staggering arrogance. It acts as if we know we can improve upon the situation. Scans and biopsies and resections and chest tubes and radiation and chemotherapy later— we say, “You’re welcome.” But we never had a solid basis to start, and we lost any evidence early along the way.

The only thing we know for sure is we gave a man side effects and kept him from doing what he loves. What we have no idea is whether he is better off.

The simple pleasures. The satisfaction of turning a screw in place. The music playing in your garage on a warm summer afternoon. In the end, that’s all many of us want. It is all I want too. To be working in that garage. I am just fortunate enough to know enough to never to subject myself to (most) cancer screening. This poor man wasn’t given all the facts, and now he was back on the scheduled for a follow up CT scan in 3 months.

Vinay, As someone who has been preaching this for decades, this it the best article Sensible Medicine has done yet. In almost all health care, the patient is the forgotten victim...and we all pat ourselves on the back for having done "what could be done". Sometimes that is fine, but often the situation is far closer to what you have laid out here.

I try to give the medical students a healthy infusion of this, but I am often a voice crying in the wilderness in this techno-therapo-obsessed world. Not everyone wants to be "saved" -- especially when the morbidity attached to such salvation is often devastating (and sometimes lethal).

Thanks for putting this in print so eloquently.

This brings to mind a conversation I once had with my primary care physician. My LDL levels were peaking, and she had just prescribed me a statin. I was curious and concerned, so I asked her about the overall impact of the statin on all-cause mortality, specifically for individuals like me with no history of MI. Her response was as chilly as the sterile examination room - a blunt, 'Are you interested in treatment or not?' That encounter marked our last meeting.