Let's Talk Peer Review

The Study of the Week explores the judging of medical science. Here are three examples that emphasize some of the limitations of peer review

The judging of science has always been contentious. But the debate used to remain among scientists.

Digital and social media, and, of course, the pandemic and its politicization of science has brought the peer review debate into the mainstream. So much so that peer-review is now a common modifier.

As in:

“This peer-reviewed paper reported…”

Or,

This preprint, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, found…”

Yet something as important as the judging of science has somehow largely escaped empirical study.

A Cochrane systematic review of only 28 studies found “little empirical evidence is available to support the use of editorial peer review as a mechanism to ensure quality of biomedical research.”

Well, that is, until last month.

The influential science journal called the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS for short) published an actual experiment to sort out “status bias” in peer review. Status bias is when prominent researchers enjoy more favorable treatment than no-name researchers.

The authors invited more than 3,300 researchers to review a finance research paper jointly written by a prominent author (a Nobel laureate) and a relatively unknown author (an early career research associate), varying whether reviewers saw the prominent author’s name, an anonymized version of the paper, or the less-well-known author’s name.

They ended up with 537 reviews. The figure tells a shocking story. Remember, this is the SAME paper.

The left side considers the rejection aspect. Here, 65% of reviewers recommend rejection if the author was a junior researcher (AL), 48% rejected an anonymous version vs only 22% reject if the prominent researcher was the author (AH).

The right side of the figure consider positive reviews. The authors considered a combination of minor revision or accept as “positive,” and you can clearly see an inverse of the relationship. 10% for the junior researcher, 24% for the anonymous paper, and a massive 59% for the senior researcher.

You might say, come on Mandrola, that’s one study. You are cherry-picking. Peer review is great!

Let me show you two more examples.

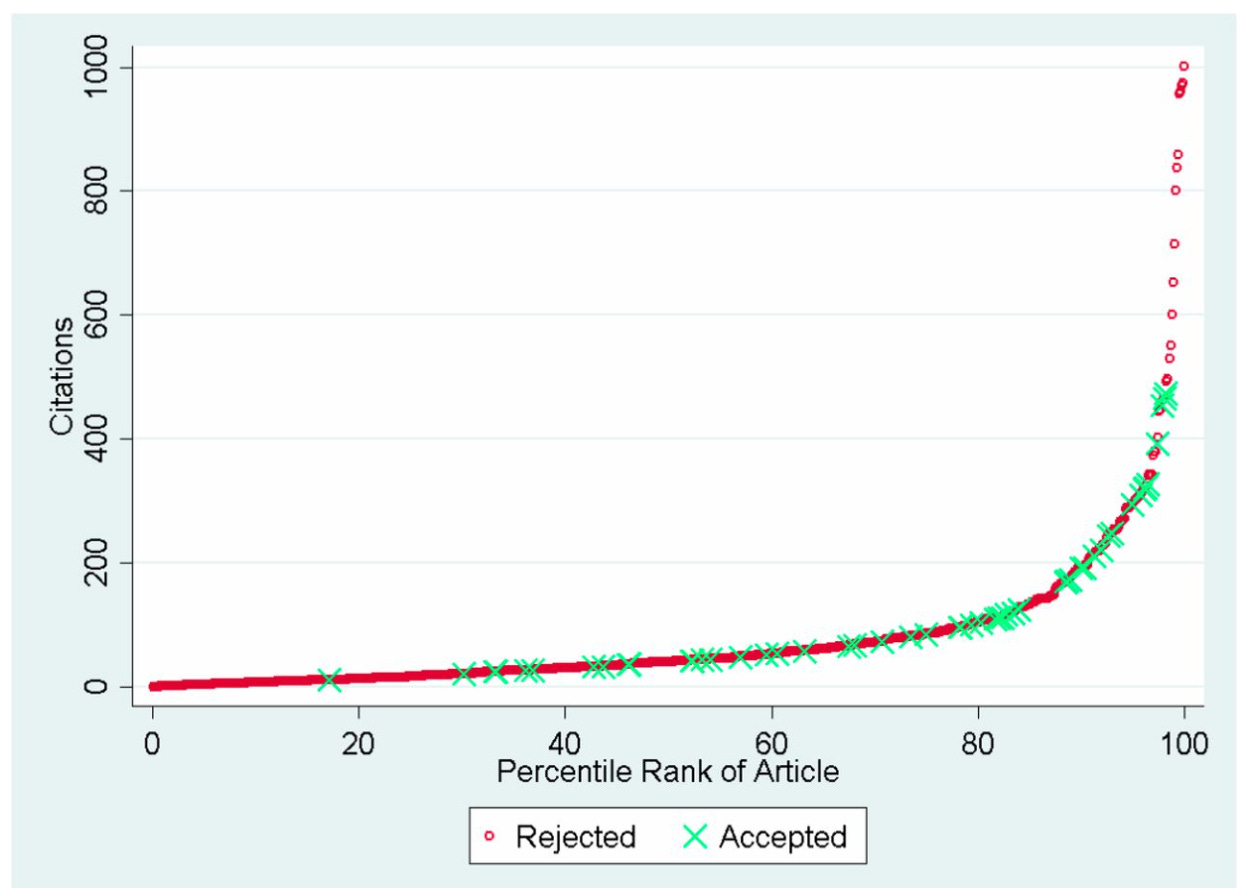

First, is from the same journal, PNAS, in 2014. In this experiment, researchers used a dataset of more than 1000 manuscripts submitted to 3 elite medical journals. The idea was to assess the citation outcomes for articles that received differing appraisals by editors and peer reviewers. In this dataset, 946 submissions were rejected and 62 accepted. Of the rejections, 757 papers went on to be published.

As you’d expect, papers that were initially rejected or received lower peer review scores ended up with fewer citations than those that passed muster. But. There were numerous questionable gatekeeping decisions.

“When examining the entire population of 808 eventually published manuscripts, our three focal journals rejected the 14 most highly cited articles.” In fact, 12 of these 14 rejected papers did not even get sent to peer reviewers. We say that the editors desk rejected it.

Look at the far right. The most important papers were rejected initially.

Here is a personal story of how a biased peer review affects the interpretation of a study.

Along with a research team at Penn State, we performed a meta-analysis of studies that compared two ways to assess patients who present with suspected coronary disease.

One way was with a coronary CT angiogram. This detects anatomic blockages. The other way was with a functional test, such as a stress test. This detects whether the blockage puts strain on the heart.

There were 13 studies that directly compared these techniques. A meta-analysis groups the results of these together—the idea of combining (similar) but smaller studies into a big one leads to more precision in the estimate.

The absolute key is that the studies be similar.

If you read our paper in the important journal JAMA-Internal Medicine, it says that patients who were evaluated with either test had no difference in future death or cardiac hospitalization. But those who had CTA imaging did have a slightly reduced chance of future MI (heart attack). Our study is now cited by proponents of CTA imaging based on this small signal.

But this finding was 100% sensitive to including one study—called SCOT-HEART--that we did not feel belonged in the analysis. Our original paper did not include SCOT-HEART because that trial compared CTA and functional stress testing to functional testing alone. It was not similar enough to the other studies—in our view.

Guess what: the peer reviewers did not accept our decision. We had the choice of publishing the paper with SCOT-HEART included or pounding sand.

Yes, we explained the fact that SCOT-HEART did not belong, and that excluding it removed the signal of MI reduction in the results and discussion section, but the abstract and main findings includes the favorable result.

Here is what we wrote— well down in the discussion section. That part is rarely cited.

Conclusion:

The point of showing blemishes in peer review is not to argue that we should do away with it.

Instead, we should understand its limitations, consider ways to improve on it and never blindly accept a finding solely because it has passed peer review. Likewise, we should also not ignore findings that have not passed peer review.

The purpose of Sensible Medicine is to elevate the level of critical appraisal of medical science. Peer review must never stop or unduly influence our thinking process.

It's hardly a secret, or surprising to be reminded, that articles first-authored by the Big Cigars in any niche area of research usually get sweet, sure, and swift treatment at the manuscript submission point relative to work first-authored by "unknown" worker bees peddling away on their varied tenure-seeking journeys in the world of "Healthcare Science". There is an unsettling whiff of corruption telegraphed by this phenomenon, yet what is really happening is very hard to pin down (which neatly nourishes the ongoing grift). Related perhaps, and also nearly laughable, is the increasingly prevalent appearance of scientific papers with giant-sized numbers of co-authors. I saw one the other day in a major journal. There were 98 names listed under its title. That's almost eleven baseball teams. Please. Enough of this bullshit already.

And - noticing that a lot of journals have pharma ads now - adding the financial component makes me wonder about rigorous scientific inquiry in this day and age. I have to say, I’m grateful - as a person with spina bifida and many related issues (including late onset crohns - I musta been a bad person in a former life! 🤣), that the majority of my surgeries and medical procedures are behind me. It’s tough to “trust the science” anymore, especially after the clear Politicization of Medicine over the past several years.