Moving the Overton Window on Bad Cancer Policy

The legacy of Malignant and the COVID19 Overton window that's moving as we speak

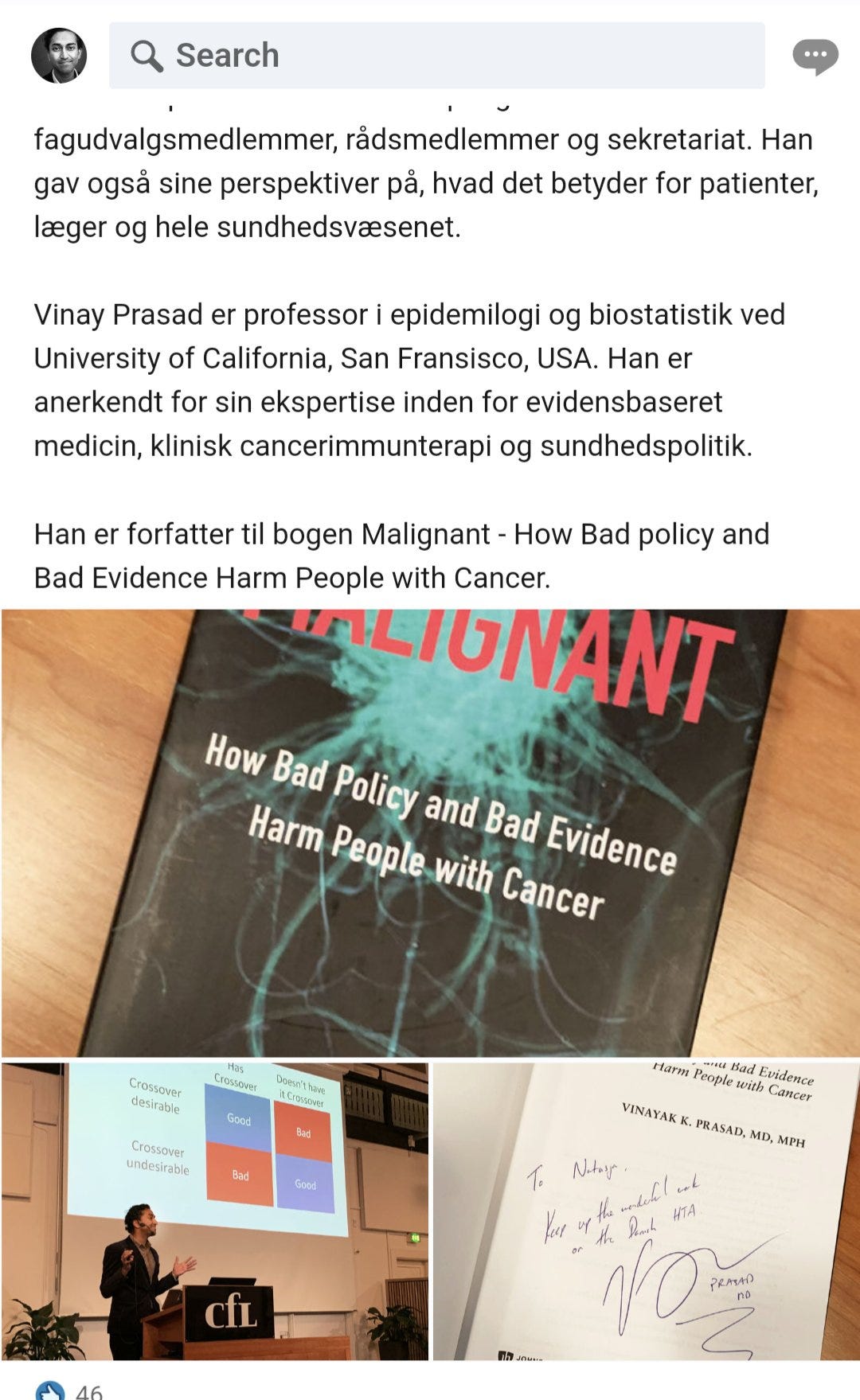

I recently got back from Copenhagen, where, in a series of 3 talks, I explored the themes of the book Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer.

What are those lessons, and why do they matter?

(Pictured with Marco Donia, MD Herlev Hospital Copenhagen)

We need cancer that drugs that extend survival, and not merely change the appearance of tumors on CT scans

Images on CT scans (e.g. Progression free survival) might not be accurate because not all patients return for the scans, and we assume they are doing similarly, but they may be doing worse (The problem of informative censoring)

We don’t do a good job of making sure patients on the control arm get the best available therapy— of course easier to show a new drug is better than a substandard comparator, but we want to know it is better than what we actually do

We don’t do a good job of making sure patients get good care after the trial (which can bias results). You need to know if drugs work in the backdrop of all the other drugs we have in the USA

I feel good that the book Malignant and the work that led up to it has begun to shift the Overton window on cancer drug policy. Now that it’s acceptable to raise these criticisms, many others are making the same points that the book introduced on post-protocol therapy, control arms, crossover, and the unsuitability of PFS as regulatory endpoint, in recent commentaries.

The same thing is coming on the topic of the mishandling of COVID 19 policy. I was opposed to school closure, which is now increasingly accepted. Next, will come vaccine mandates and masking toddlers (which I also opposed). Finally, the field will admit that not running randomized trials and giving out paxlovid like skittles was unsound.

At last, we may come to the conclusion, that the majority of the COVID19 response was harmful. The sensible strategy would have been to protect elderly and nursing home patients (with focused protection), have everyone else continue normal life, and vaccinate the elderly (voluntarily) and then call it day. Eventually, most academics will come to this conclusion, which is essentially the position of Sweden and other parts of Europe. The GBD authors were far more accurate than their critics. The Overton window is moving.

Cheers from Copenhagen!

(PS back now in San Francisco and the sidewalk is much dirtier).

After 40 years in Critical Care, ID, HIV, COVID-19 and reading Malignant have created in me much cognitive dissonance about my profession and my practice.

I’m been through PA Catheters, DaO2 of 660 ml/min/m2, Intensive Insulin, Central lines, CVP, CVO2, and steroids for sepsis and XIGRIS (!!!). How ‘bout freeze-drying post Cardiac Arrest patients? Many were based on poor quality studies and magical thinking.

Since discovering Vinay I’ve begun to read articles more critically and inclined to question the next new thing.

SMART Physicians like Vinay will help navigate the way back to sanity.

This is the same issue in cardiology. We want to see trials powered to show benefit in hard clinical endpoints; not in a bunch of surrogates markers, and/or soft outcomes absent proper blinding/sham control. We need regulators to demand this level of evidence before providing approval (for devices and meds) as this is the only incentive with teeth that will compel such studies to be done by sponsors/proponents.

As for proper “control arms”, I would concede a small bit to some of the researchers, in that “standard of care” might actually evolve during the course of study follow up (and about which investigators could not have foreseen or predicted). But equally obviously, control arm therapies should at least be “state of the art” at study onset.