Oseltamivir Continues to Teach Us Lessons

The specific story includes yet another failure of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) to provide benefit in the treatment of influenza.

The larger story is why some therapies persist in the absence of any evidence of benefit.

JAMA-IM published this month a meta-analysis of 15 randomized clinical trials of oseltamivir vs placebo for the prevention of hospitalization due to influenza infection.

The McGill University research team included 15 trials of more than 6200 patients. Each trial used the standard 75 mg twice daily dosing for 5 days. They excluded observational studies—due to the risk of bias.

The mean age of patients was 45 years. Their primary efficacy outcome was the first all-cause hospitalization. (The choice of all-cause hospitalization is important because infection can trigger other issues, such as asthma, arrhythmia or heart failure.)

They also had a primary safety outcome of any adverse event.

Main Results

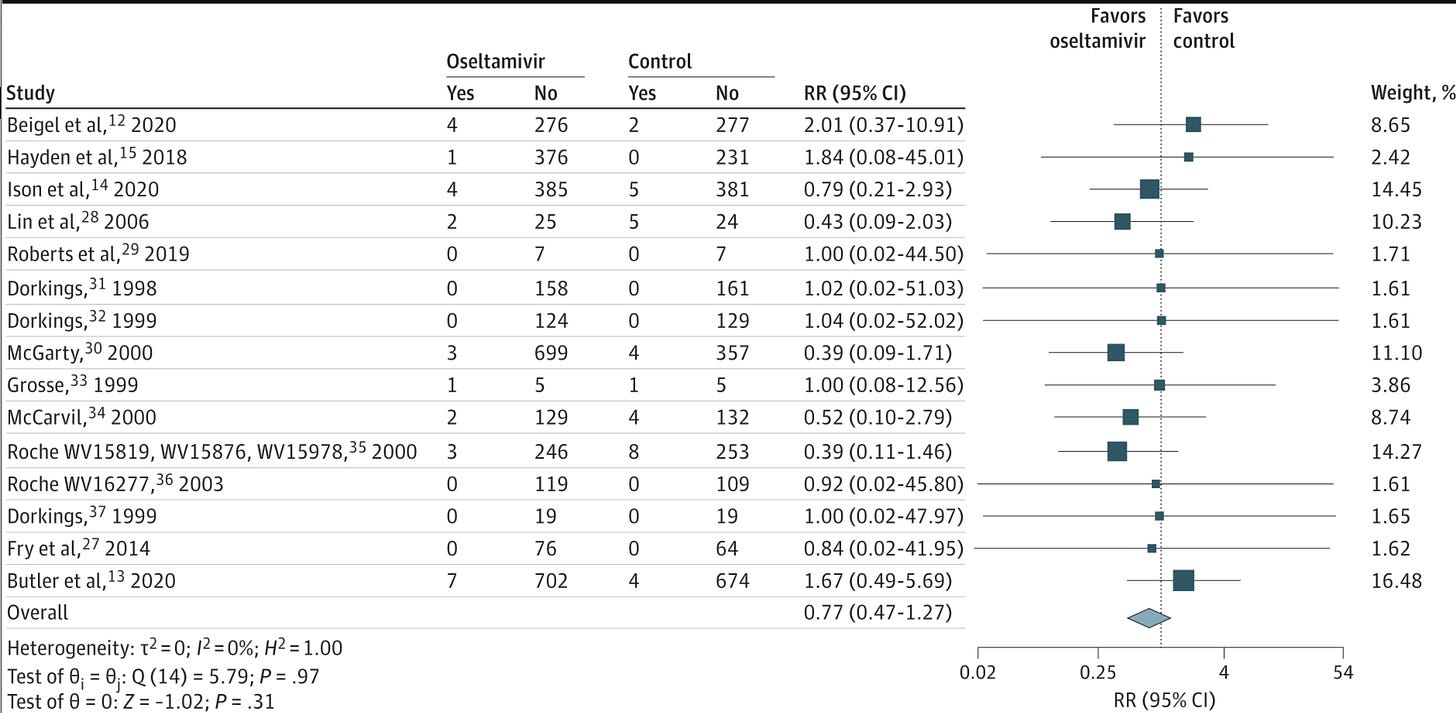

The results of meta-analyses are best depicted in forest plots.

Each line in the picture above depict the results of the individual study with the point estimate, confidence intervals and study weight.

You can eyeball the plot and see that each study hovers the null effect. The summed effect, shown in the green diamond also hovers the null and is not significant.

The authors conclude that oseltamivir was not associated with a reduced risk of all-cause hospitalization.

One counter argument I hope you are considering is that perhaps the young age of included patients explained the lack of effect.

The authors showed in subgroup analyses that oseltamivir had no special effects in higher risk or older patients.

Another question I hope pops into your mind is the absolute risk of hospitalization.

Meta-analyses like these report relative risk reductions. But one of the reasons it is hard for therapies to show benefit is that the absolute risk of events may be so low that it’s hard to make it much lower. (This is a big issue in cardiac and screening trials. This is good news, of course.)

In this summary of 15 trials, the overall risk of hospitalization in the placebo arm was only 0.6%. So it is hard to make something so low that much better.

Adverse Event Findings

Oseltamivir use associated with a statistically significant 43% increase in nausea and 83% increase in vomiting but no significant increase in serious adverse events, such as neurological disorders.

Comparison to Previous Studies

Oseltamivir has a dubious past history. Many years ago, the company that made oseltamivir, and sponsored the original trials, convinced governments to buy millions of doses of the drug to stockpile it for future pandemics.

The McGill team wrote this sentence in their intro:

Detailing by key opinion leaders, guideline panels, and the manufacturer has even led to stockpiling of the medication as part of national pandemic responses.

They cited this Reuters article

The study that prompted such a clear headline came from Tom Jefferson and colleagues at the Cochrane Collaboration.

Along with help from the British Medical Journal, Jefferson and colleagues were able to obtain the actual clinical study reports (aka-raw data), from 83 of the original studies. It was not easy. BMJ actually published the correspondences that led to release of the source data.

They published their findings in this massive systematic review in 2014.

With the help of open data, they found that oseltamivir reduced the time to first alleviation of symptoms by 17 hours. They found no effect in children with asthma.

In treatment trials there was no difference in admissions to hospital in adults (risk difference 0.15%, 95% confidence interval −0.91% to 0.78%, P=0.84).

They also found no reductions in bronchitis, otitis media, sinusitis or any other serious complications.

Similar to the McGill authors, Jefferson and colleagues also reported significant increases in nausea and vomiting.

Why Has Oseltamivir Use Continued?

In January of this year, Sensible Medicine featured a piece from Dr Mark Buchanan in which he asked why his healthy 10 year-old grandson received a prescription for oseltamivir.

His piece reflects the real-world situation. This winter I saw many patients tested for influenza so as to receive oseltamivir. In 2023! Nine years after Jefferson’s definitive study.

Some of you may posit that money drives use of non-beneficial therapies. I would partially agree. But the sclerosis of many therapeutic fashions turn on more than money.

Consider that no one is making money from prescribing oseltamivir.

My idea is that nonbeneficial therapies persist because of three main factors: excess optimism, ignorance of history and laziness.

A Recent Example

Vinay chronicled the story of the shingles vaccine preprint.

Here was an observational study that reported a possible reduction of dementia (only in women) that associated with getting a shingles vaccine.

This was an obviously flawed analysis—not even published in peer-review form. Yet it received more than 4000 retweets, most of which were positive.

Why? A: Excess optimism, ignorance of history and laziness.

Dementia is terrible and people want something to work. They want to be optimistic.

These same people also don’t consider medical history. Their priors are way too hopeful. Even a cursory look at medical history reveals that most things don’t work.

And then there is laziness. How many of those 4000 online supporters actually read the study? For if they had read it, they would have learned that the effect size for the reduction of dementia was greater than the reduction of shingles. A strong sign of noise not signal.

The aim of our effort here at Sensible Medicine is to promote the value of critical appraisal. We are not nihilists. We aim to be a place where people can read independent thinking.

Thank you for your continued support. And excellent comments. Please feel free to disagree with me. Or add your ideas as to why nonbeneficial fashions continue.

I propose a fourth reason why "nonbeneficial therapies persist" - capture of regulatory health agencies by big pharma. They could do more ( if they do anything at all) to get information out to physicians, healthcare workers and the public about the updated evidence. For some reason they don't 🤔- 💰until the regulatory and med school capture is repaired I don't think much will change.

Another likely reason Dr's write it is because patients want it. Patients/consumers have been told it works and now consider it "the standard of care." They become disgruntled when an apparently effective treatment is denied them. So, for the physician, it is easier to write it. Side effects are seemingly limited and, thus, so is the downside to prescribing it. As opposed to an unhappy patient, sick with the flu, who believes that their doctor isn't doing anything for them.

This is another deleterious result of the travesty of direct-to-consumer advertising.