Post #2 Back-to-Sleep Series

The Back-to-Sleep recommendation has potentially significant downsides

In Post #1 last Wednesday, Elizabeth Fama introduced her critical appraisal series on the Back to Sleep recommendation. This week, she explores the downsides of sleeping babies on their backs. JMM

Possible Downsides of Back Sleeping

Sleep Quality

For adults, it’s fairly interchangeable to sleep on the stomach, side, or back. This may not be true for infants.

A 2015 Nature (Pediatric Research) paper by Nils J. Bergman summarizes a body of research that confirms the benefits of sleeping on the belly.

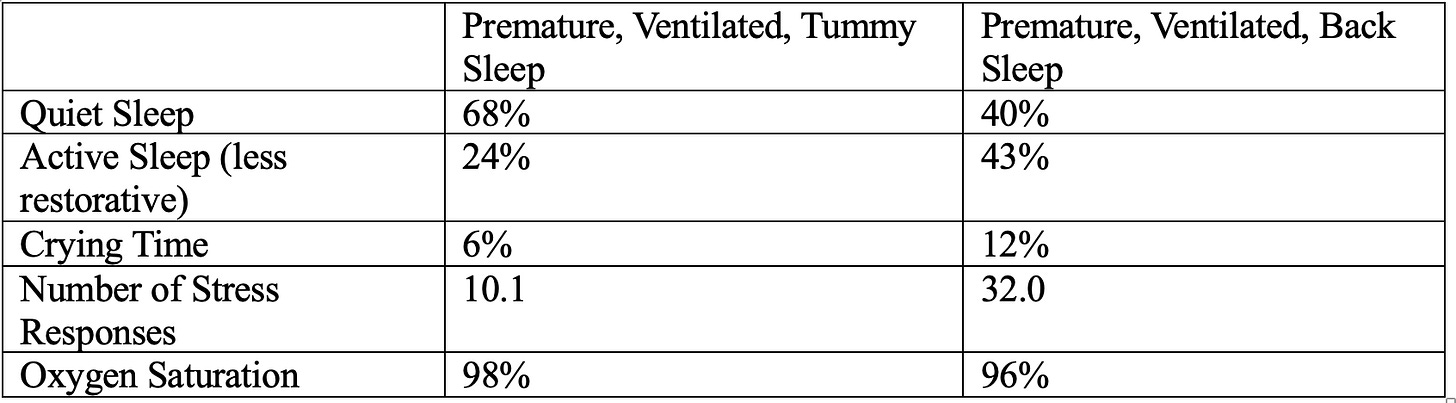

For example, Bergman reports a 2002 study in which ventilated premature babies were placed to sleep on either their tummies or backs, and the following states were measured: quiet sleep, active sleep (which is less restorative than quiet sleep), crying time, number of stress responses (startle, tremor, and twitch), and oxygen saturation.

This is an astounding difference in the quality of sleep, and to this day, premature infants in the hospital are slept on their stomachs. Moreover, a 2014 Brazilian study shows that prone-sleeping premature babies have lower salivary cortisol concentration, a better Brazelton sleep score, and a lower respiratory rate, indicating deeper sleep.

The prevailing model of SIDS (the Triple-Risk Model) says that SIDS occurs in infants who have an underlying vulnerability (the “intrinsic risk”), plus an external threat or threats like prone sleep (the “extrinsic risk”) and are in the critical developmental period of being under a year old (especially between two and four months of age). Examples of vulnerabilities include damaged central-nervous-system homeostatic control of arousal, and cardiac ion channelopathies. In deep sleep, a baby with a subtle deficit in the ability to self-arouse may experience an apneic episode or an exposure to her own exhaled carbon dioxide (trapped by bedding, for instance), and is unable to initiate the gasping reflex.

Bergman surmises that back sleep helps to prevent SIDS by keeping the baby in a state of semi-arousal, interrupting the deep-sleep stage that is suspected of being risky for those who have hidden autonomic or cardiovascular conditions.

If this mechanism is accurate, it seems possible (to me) that loss of quiet sleep could have costs, and be detrimental to brains that are growing as fast as an infant’s. Sleep affects learning, memory formation, and physical growth. There is evidence that, for children and adults, elevated cortisol levels and chronic stress can lead to behavioral, mental-health, and mood issues, as well as changes in inflammation and immunity.

It seems telling that as soon as babies gain the ability to roll over, they most often choose to sleep on their bellies.

Plagiocephaly

Positional Plagiocephaly, or PP, is a flattening of the baby’s head that can result from exclusive back-sleeping. Since the successful Safe to Sleep campaign, the prevalence of PP has increased from 5% to up to 46% at age 7 months. Research by Collett et al (2018) shows that, despite some improvement in PP by 18 months, the deformations persist beyond 36 months. And while PP is mostly aesthetic, severe cases are usually prescribed physical therapy and sometimes orthosis (helmets), although Collett et al shows that the outcome is the same with or without physical therapy, and with or without orthotic treatment. There is some evidence that PP may increase the need for orthodontic treatment.

PP must also be distinguished from a serious condition called “craniosynostosis” (head-shape anomalies) that results from early suture closure in the bones of a baby’s skull, and which can require surgery to allow normal development of the skull and face. I found no data on how many excess pediatric and craniofacial-specialist visits PP has consumed over the years to rule out craniosynostosis. I also wonder whether there are cases of craniosynostosis that are missed because parents and pediatricians misdiagnose them to be the more benign PP. These would both be hidden costs to back sleep.

Delayed milestones

With the advent of the Back to Sleep campaign, babies are achieving key developmental milestones later than older generations: lifting their heads, rolling over, sitting unsupported, walking, and fine motor skills of the hands.

Among our friends and family, anecdotally, some babies are not crawling at all before they begin walking, perhaps because they don’t fully develop the upper-body strength required for crawling. There are few studies about crawling, but all of them show positive outcomes from achieving the skill: shoulder stability, abdominal and hip strength, hand-eye coordination, and joint stability. Young children who skipped crawling have inefficient pencil grasp, and non-crawling nine-month-olds may have less flexible memory retrieval. Crawling may promote depth perception, problem solving, and spatial awareness. I suspect that it gives confidence to a baby to be a human Roomba on the floor, exploring rug fringes, the dog’s water bowl, and legs of chairs, all the while learning emotional resilience in her environment.

Rather than investigate the potential health implications of delayed milestones, medical authorities seem to have pushed back expectations of those skills.

In 2022 the CDC paid the AAP to form an expert working group to revise its developmental surveillance checklists. In the resulting document, the working group changed the ages at which children can be expected to reach developmental milestones. The biggest change was to stop reporting when 50% of children can be expected to reach a milestone, and to instead report an age when 75% can be expected to have reached it. This step, they said, was designed to make it easier to identify children who are falling behind. But it also masks the fact that absolute skill levels have declined. The changes to the guidelines, along with adding milestones for the 15- and 30-month well-baby visits, “resulted in a 26% reduction and 41% replacement of previous CDC milestones. One third of the retained milestones were transferred to different ages; 68% of those transferred were moved to older ages.”

To quantify the diminished skills of infants, I compared the new CDC milestones with classic screening tests like the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the Denver Developmental Screening Tests (DDST). The DDST reports the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile, allowing us to compare their 75th percentile with the CDC’s new 75th percentile guidance. Let’s look at 1967 vs. 2022 for the DDST and the CDC:

Or, more vividly:

A 1967 baby is rolling over while a 2022 baby is still pushing up onto her arms when on her tummy.

A 1967 baby is sitting without support while a 2022 baby is rolling over.

A 1967 baby is raking a raisin toward herself with her fingers and attaining it at 6.2 months, while a 2022 baby is raking a raisin at 9 months.

For a brief moment in the late 1990s, scientists tried to answer the question of when children make up for the developmental delays possibly induced by back sleeping.

Two 1998 studies, one in the US and one in the UK, found that the gross motor skills, social skills, and total developmental score of front-slept babies were higher than back-slept babies. The US study, which followed developmental milestones from birth until the subjects walked, found significant differences in five of the eight motor milestones they studied, but found no significant difference in age when infants walked. The authors encourage pediatricians to "provide parental reassurance that the differences in milestone acquisition are not developmental delays, but rather are still within well-accepted normal ranges for development.” Yet they admit that “…further studies are indicated as this generation of primarily supine sleepers becomes older.”

The UK study gave parents developmental questionnaires when their children reached six months and eighteen months and concluded that many of the differences were no longer apparent at eighteen months. These authors write, “Weighing this [transient disadvantage] against the adverse health effects demonstrated with the prone sleeping position, should not change the message of the Back to Sleep campaign.”

However, the developmental delays beyond eighteen months, noted in my chart, may call the transience into question.

Other Potential Unintended Consequences of “Safe to Sleep”

Low-quality sleep, plagiocephaly, and developmental delays are the most serious possible downsides of the Safe to Sleep campaign, but they are not the only ones. Pediatricians and health policy advocates have had to create multiple patches for the unintended consequences of back sleeping, and a multi-billion-dollar industry of merchandise and consulting has rushed in with its wares and expertise.

The Beginning of Tummy-Time

Babies who sleep on their fronts will naturally and gradually develop the necessary strength to hold up their heads, push themselves up using their arms, and roll over. Babies who sleep on their backs are slower to develop these strengths. And so “tummy time” was invented, which approximately zero babies want to do. A google Ngram of the term “tummy time” shows the phrase taking off in American English around the year 2000.

Tummy time involves playing with the baby on her stomach during wakeful periods. The goal is that she will develop neck, arm, and upper shoulder girdle strength by lifting her head and eventually pushing her chest off the ground. In our house we refer to it as physical therapy, which is a more honest term.

The recommendation is to start with 3-5 minutes per session, several times a day, working up to an hour a day by the time the baby is three months old. Doing the math, in order to achieve an hour a day in 3-minute increments, an adult must do physical therapy with the baby twenty times a day. Keeping in mind that babies nap a few times a day, you’ll be hard-pressed to get all this PT done.

A 2018 study showed that childcare centers in Australia and the US self-reported 75% and 100% compliance with tummy-time sessions, respectively, for children under six months of age. A 2017 paper found that 49.6% of low-income Hispanic moms self-reported implementing tummy time daily, but only did it an average of 1.87 times a day, and only 24.1% had ever used the floor for tummy time. Anecdotally, our friends and family express guilt over not insisting on enough tummy time with their resistant infants.

Why does tummy time make babies miserable? Placing or rolling newborns into tummy time is like taking adults to the gym and making them do overhead presses when they’ve never lifted a single weight before. The adults might wail, too. Our own granddaughter (who is paradoxically both headstrong and sensitive), found tummy time so upsetting that she seemed to master tummy-to-back rolls solely to get herself out of tummy time. She was much slower—perhaps militantly—to learn the more useful back-to-tummy rolls.

Swaddling

The Moro reflex is the involuntary startle response that happens because of a noise or sudden movement, but often for no reason at all. The baby’s arms and legs fly out and they arch their backs before curling in. It happens more often when babies sleep on their backs. The patch? Swaddling during sleep sessions until the infant is three or four months old—that is, making babies spend a couple of thousand hours of their early life not using their muscles at all, so that they might stay asleep a bit longer.

An entire industry has exploded, devoted to zippered, Velcro-crisscrossed cloth swaddles, some that fortunately allow the legs to flop to the sides in the hip-safe “froggy” position. One brand of swaddle touts its “gently weighted Cuddle Pad” that “provides gentle pressure (similar to tummy sleeping)” to help soothe baby to sleep [italics mine]. When an infant outgrows swaddling, sleep sacks with two-way zippers are the alternative to unsafe blankets to keep her warm on chilly winter nights. (I heartily endorse sleep sacks, because blankets don’t stay put.)

Black Out Curtains and Rocking Bassinets

Sleeping on the back is visually too stimulating for a semi-aroused brain, so an industry of blackout curtains—including stick-on varieties—has sprung up, along with white-noise machines and “smart” night lights that allow parents to navigate in the pitch-black room.

The epidemic of poorly sleeping babies has jump-started a high-end of merchandise, too, starting with the Snoo and its recent imitators. For a couple of thousand dollars, you can buy a bassinet that straps your baby down and soothes her back to sleep with a rocking motion while she lies supine in a straitjacket on a flat mattress surrounding by breathable mesh walls. You can add an Owlet sock on her foot for $369 with a sensor that measures her heartrate and oxygen saturation, or a $249 Nanit band across her diaphragm to document that she is breathing, and alert you if she stops.

These last two sensor devices (along with their very helpful night-vision cameras) seem reasonably scientific to me, but so far, the AAP expressly recommends against them, perhaps because they worry parents will use them as tools to relax the Safe to Sleep rules.

If you do a search on “sleep consultant certificate course” you’ll find many websites. Focus solely on those that are approved by the Association of Professional Sleep Consultants—noting in your search that there is also an International Association of Sleep Consultants, and a World Association of Certified Sleep Consultants—and you’ll see twelve certified training courses. Now search “sleep consultant near me,” to find a local practitioner and, if you live in a city, there will be enough that you’ll have trouble choosing between them.

In her post next week, Ms. Fama will discuss what is known about SIDS: the rates of SIDS deaths, what it takes for a death to be classified as SIDS, and the coincidental decline in deaths of all causes.

35 years of Peds practice have noticed the shifts in development of infants and also frazzled parents with babies who cannot sleep on their back. 10 years ago I threw the back to sleep philosophy in the trash and educated parents about avoiding the multiple other risk factors. I quit the AAP when their asinine policy of masking toddlers and saying it didn’t affect speech development was rolled out. And don’t get me started on the total lack of evidence based medicine in policies advocating Covid vaccine for children. Also the tunnel vision in ONLY advocating gender affirmation in dysphoric preteens, ignoring a plethora of other causes for angst and dysphoria in this age group. The list goes on and on.

Great writing. Now loop in the factor of the exponentially increased childhood vaccine schedule since 1986, and consider that SIDS is downstream of neurological damage caused by the adjuvants in the inactivated vaccines. The "back to sleep" campaign is downstream of SIDS. And as you have shown, children are developmentally delayed comparing to 2 generations ago (not to mention the explosion of chronic diseases ).

Time to ask the hard questions about every medical intervention and food products we consume