Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras: A Critical Appraisal

A critical appraisal

A few month ago, we were pleased to publish a critical appraisal written by a group of students at the Wayne State University School of Medicine. The group is back with another piece about a recent article. I am enjoying this way of encouraging critical appraisal in undergraduate medical education and generating good content for Sensible Medicine.

As below, please take this opportunity to appraise the appraisers.

Introduction

In 2020, the term “Long COVID” was adopted to describe persistent symptoms after a COVID-19 infection. The scientific community has since adopted the more formal designation, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Researchers like Dr. Zayid Al-Aly have been at the forefront of advancing our understanding of the long-term outcomes of COVID-19. His work earned him a spot in TIME's 100 Most Influential People in Health for 2024. His methodology, however, has drawn criticism. In this post, we review one of Dr. Zayid Al-Aly’s recent paper published in NEJM, Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras.

Question

How has the risk and burden of PASC evolved throughout the pandemic?

Design/Setting/Patients

The study utilized the VA Health Care System database, comparing 441,583 individuals who survived at least 30 days after an initial COVID-19 infection to 4,747,504 non-infected controls. The study examined these populations between March 1, 2020 and January 31, 2022, covering three COVID-19 variant periods including the pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron eras. The infected cohort was divided further into unvaccinated and vaccinated patients. Participants were followed for up to one year or until death, reinfection, or their first infection (for the non-infected group) to evaluate the risk of PASC.

Outcomes measured

The study used health outcomes related to ten disease categories as indicators of PASC.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Results

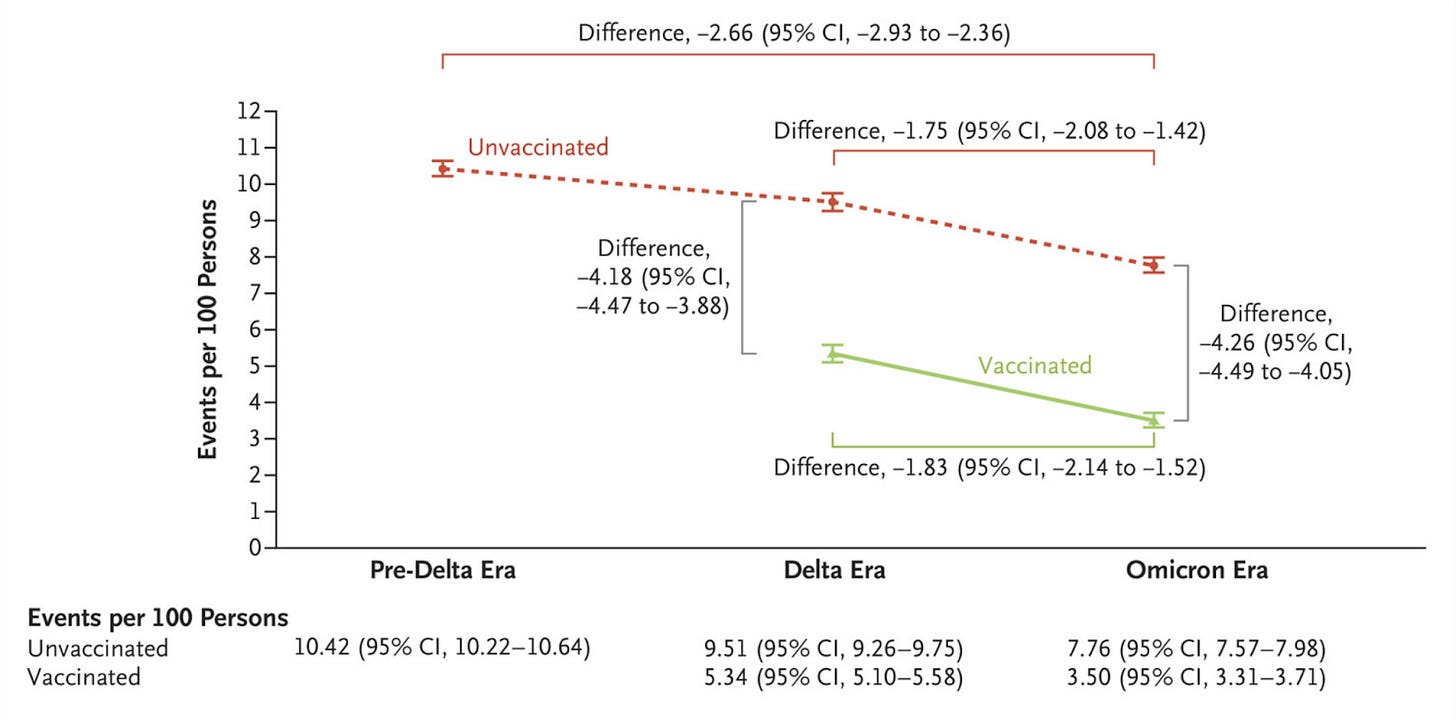

The study reported a decline in PASC incidence over time. Among unvaccinated individuals, the incidence of PASC (events per 100 persons) within the first year of infection was 10.42 during the pre-delta era, 9.51 in the delta era, and 7.76 in the omicron era. In vaccinated individuals, the incidence was 5.34 during the Delta era and 3.50 in the Omicron era. This reduction was attributed approximately 70% to vaccination and 30% to other temporal effects. This is displayed in the figure below.

The greatest reduction of sequela were observed for cardiovascular, mental health, and pulmonary (highlighted in red). An increased risk of sequela of gastrointestinal, metabolic, and musculoskeletal was found in the unvaccinated group (highlighted in orange).

Author Conclusion

Both temporal effects and vaccines contributed to the decline in PASC incidence, but a significant residual risk remains, even among the vaccinated population who previously had a COVID-19 infection in the omicron era.

Commentary

Studying PASC is difficult and no study will be perfect. The syndrome remains poorly characterized. Inclusion as an affected patient requires that person to self report symptoms. All studies must be observational.

A concern with this paper is that the broad list of conditions included in the disease categories may inflate the reported PASC incidence. In Table S2 (reproduced below), 88 diagnoses are grouped under the umbrella of PASC. Each of these diagnoses have many potential etiologies. While the broad inclusion criteria was useful for early research due to the novelty of the condition, continuing this approach of inclusivity (sensitivity) over specificity risks overestimating the true incidence. Without a more nuanced stratification of conditions based on their direct association with COVID-19, studies may conflate the long-term effects of the virus with unrelated health issues. This concern applies across other disease categories listed in Table S2, where conditions like anxiety, fatigue, or gastroesophageal reflux disease, which are prevalent in the general population, further muddy the interpretation of PASC-specific outcomes.

The problem of non-specific inclusion criteria are complicated by how the study identified the infected cohorts. Patients with multiple comorbidities are known to experience worse COVID-19 symptoms, leading to a greater likelihood of hospitalization compared to healthier individuals [Kompaniyets 2021]. This introduces bias, as those with preexisting conditions are both more vulnerable to severe illness and more likely to develop complications (or have symptoms) that may be classified as PASC. Additionally, during the early stages of the pandemic, hospitals tested both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. This broad testing strategy, while advisable as a public health intervention, likely captured incidental cases of infection, further skewing the study population towards individuals with significant underlying health issues who may have been hospitalized for reasons unrelated to COVID-19. These factors combine to create an infected cohort that is sicker, apart from the COVID infection, than the control group. While the authors employed several methods to control for confounding, the inclusion of a disproportionately high-risk population may inflate the reported incidence of PASC and blur the distinction between COVID-related outcomes and the natural progression of preexisting conditions.

Concerning specific disease sequelae, the most significant declines in PASC were seen in cardiovascular, pulmonary, and mental health categories. This comes as no surprise. The reduction in cardiovascular and pulmonary complications which are associated with disease severity is likely attributable to viral evolution and greater population immunity. The improvements in mental health outcomes might be associated with easing of lockdown restrictions and the return to social and economic normalcy.

Interestingly, gastrointestinal, metabolic, and musculoskeletal sequelae increased among unvaccinated individuals. The authors acknowledge this by stating that the data "suggests a differential, non-monolithic shift in the phenotypic features of PASC as a consequence of changes in the characteristics of SARS-CoV-2." If these manifestations were truly part of the PASC disease spectrum, similar trends should have appeared in vaccinated cohorts, yet they did not. Stratifying by disease severity would provide more critical insights, but this level of analysis was not undertaken. Without stratification, it is difficult to determine whether these findings reflect the natural evolution of the virus or simply healthcare-seeking behavior after a period of limited access.

Another issue to note about the paper, one that perhaps speaks more to this area of research, is the reliance on self-citations. Sixteen of the twenty-five citations are the authors’ previous work. The justification for using ten disease categories to define PASC is the author's own work. This reliance on self-referencing creates an echo chamber, limiting the breadth of external evidence considered in the study.

Conclusion

PASC remains extremely difficult to study. While the authors should be commended for this work, the findings must be interpreted with caution. The broad inclusion of conditions, potential confounding due to cohort formation and reliance on self-citations diminish the strength of its conclusions.

I don’t understand why people think they can draw meaningful conclusions about the benefits of the covid vaccines by using observational data.

For example, a study done in Israel claimed a 90% reduction in fatalities by taking the covid booster. The raw data showed a 94.6 % reduction of covid deaths in the vaccinated arm. Looks impressive! The authors of the study left out an important detail.

Tracy B. Høeg, Ram Duriseti, and Vinay Prasad discovered that the data from that study showed the NON covid death rate in the vaccinated was also 94.8% lower. When you read the study, you think the vaccines are a miracle. But when you see the full picture, it looks like the vaccines are useless at best. This is far from the only example showing an extreme healthy vaccination bias.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2306683

Observational studies showing benefits for the covid vaccines are meaningless. The machine will never stop trying to convince the public how great these vaccines are. The people have heard so much BS they are growing more skeptical.

good start... but you guys seem far to generous... this paper seems like a whitwesh to try to justify vaccine use/mandates... I think you should focus on why the vax effects were likely way overstated and why the paper should have never been published as evidence of yet more corruption and heathcare malpractice during covid era

oh and one small nitpick: testing of asympt people was never a good idea. this bucks long standing resp virus best practice (see pandemic planner)