PRAGUE 25: A "negative" trial for weight loss in AF, but with hugely "positive" signals

The Study of the Week address a bold trial that puts catheter ablation of AF to its most serious test. You have to look past the primary endpoint.

In Western countries, the incidences of atrial fibrillation (AF) and obesity have risen in parallel. And this relationship goes beyond association. Taken together, the evidence clearly supports the contention that obesity can cause AF, through many biologic mechanisms.

The therapy implications are obvious: if obesity causes AF, then weight loss should reduce AF. Yet this has been hard to demonstrate. A small RCT more than 15 years ago suggested a program of risk factor management (including weight loss) reduced AF episodes compared to normal care. But other trials have not confirmed these findings.

Most of the weight loss and AF data come from observational studies. The Adelaide group have published numerous studies that find that obese patients who achieve either weight loss or fitness or both have less AF. The limitations are obvious: a) it’s hard to replicate the Adelaide approach and b) patients who achieve that degree of weight loss are probably special in other ways.

Perhaps the main impediment to demonstrating that weight loss is a proper strategy for AF stems from simple human nature. For the doctor caring for a patient with both AF and obesity, the AF is much easier and more lucrative to address than the obesity. You can ablate the AF, get paid a lot, declare victory and send the patient back to the referring doctor still with diabetes, high blood pressure and impaired quality of life.

The Trial

The PRAGUE 25 trial, performed in 5 centers in the Czech Republic, boldly put to test the weight loss strategy vs ablation in patients with obesity and AF.

It was a simple trial that compared patients with obesity (mean BMI 35) and symptomatic AF to get either catheter ablation or aggressive lifestyle modification with antiarrhythmic drugs. The lifestyle arm included a weight management program with dietary and exercise specialists using tech support via mobile phone apps and regular in-person and telephone conversations.

The primary endpoint choice was freedom from an AF episode more than 30 seconds after a blanking period. The authors also measured many secondary measures—which turn out to be important. Stay tuned.

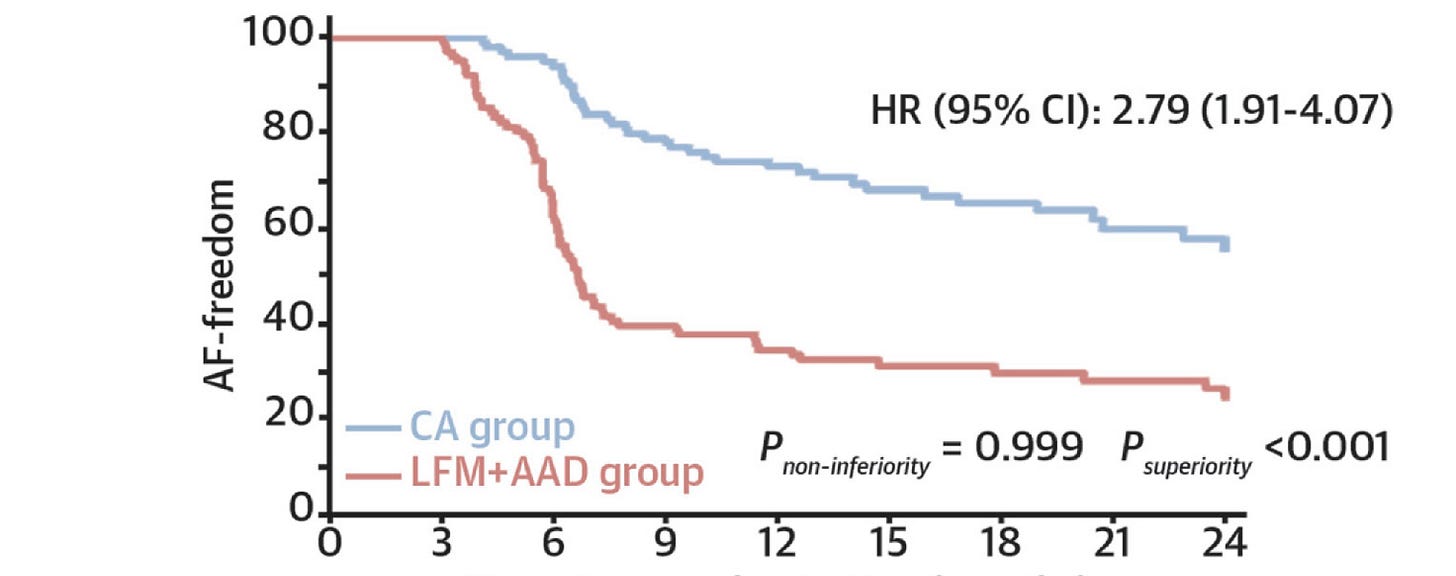

The results (for the primary endpoint) clearly favored catheter ablation. The percentage of patients with AF freedom at 12 months was 73% in the CA group and 35% in the LFM/AAD group. The HR was 2.8 (95% CI 1.9-4.0). You don’t need statistics. You can clearly see that ablation was better.

So the conclusion has to be that catheter ablation was superior to lifestyle management combined with drugs in improving freedom from AF at one year.

But. But.

Four important nuances:

Weight loss was significantly greater in the LFM group (6.4 kg vs 0.35 kg).

Glycemic control was better in the LFM. HbA1c decreased by 1.4 ± 4.8 mmol/L in the LFM while it increased by 2.5 ± 10.5 mmol/L in the ablation arm.

Fitness as measured by VO2 max was also better in the LFM group. (+1.14 ml/kg/min vs +0.15 ml/kg/min).

AF burden, which is arguably a more relevant endpoint than freedom from a 30-second episode, did not differ significantly in the two arms. The numerical decrease was larger in the ablation arm (31% to 12%) vs the LFM (36% to 22%) but the between group difference did not reach statistical significance.

Consideration of the Limitations Further Favor a Conservative-First approach to patients with obesity and AF.

One limitation is that patients in the LFM achieved only a modest weight loss of 6 kgs, which was less than 10% of their body weight. Previous observational studies associate a 10% body weight as a key measure for AF reduction.

PRAGUE 25 was done before the era of GLP1 drugs, which would surely enhance weight loss—and preliminary data suggests that GLP1 drugs may reduce AF. Repeat the trial with GLP1 drugs and the results could be much different.

Another limitation was that sleep apnea was not aggressively addressed. Many, if not most patients with obesity, have sleep apnea. Adding sleep apnea treatment may have helped the LFM arm.

My Conclusions

While catheter ablation reduced the endpoint of freedom from 30 seconds of AF, it tied or lost on all other endpoints.

Quality of life measures were not different. Neither was AF burden, though the trial did not use implantable loop recorders and may have underestimated AF burden.

Catheter ablation lost on the important health measures of weight loss, glycemic control, and fitness. What’s more, more than a third of patients with symptomatic AF did not have even 30 seconds of AF in 12 months.

To me, PRAGUE 25 rests in the literature as a “negative” trial for lifestyle management vs ablation. But for those of us focused on the overall health of our patients, it clearly supports a lifestyle management program before ablation.

For if you only ablate AF in these patients, you clearly achieve lesser health status.

For me, the most troubling statement in this essay is "declare victory and send the patient back to the referring doctor still with diabetes, high blood pressure and impaired quality of life." Given the statistics, it's obvious that obesity causes greater disease burden and lower quality of life. Yet the medical system is organized around highly siloed specialists independently treating different sequelae rather than attacking the underlying causes of illness in a coordinated manner.

Nice review of this important trial. The takeaway for me is an all-of-the-above approach: catheter ablation for selected patients who will benefit from the procedure and LFM for everyone. I have had a few patients who chose LFM first and did not return for ablation, but it is the exception. I do tell every patient that LFM will do more for your long-term cardiovascular health than anything I can do and will reduce your risk of needing a repeat procedure. I also include alcohol reduction for habitual daily or binge drinkers.