Prediction is Hard Especially About the Future

Cardiac risk scores can be useful for populations but not so much for you.

Social media often shows me (and likely you too) people who maximize efforts to avoid a myocardial infarction or stroke. These folks calculate risk, get scans, take supplements etc.

Today I will show you a recent paper from a group in NY city which describes how hard prediction can be on an individual basis. We will learn about the MI paradox.

Here is the idea: heart disease is a leading killer; it’s modifiable through lifestyle and medication and therefore we should screen for it so as to avoid it.

The main screening tool is a risk calculator. You simply input your age, BP, some lipid numbers and a few yes/no questions (smoking or not) and voila, out pops a 10-year risk.

If your 10-year risk is sufficiently low, you are reassured and no further evaluation is done.

But is this correct? Indeed…this reassured group was the main focus of the study. The authors also reviewed the predictive ability of warning symptoms.

Buckle up.

The Study:

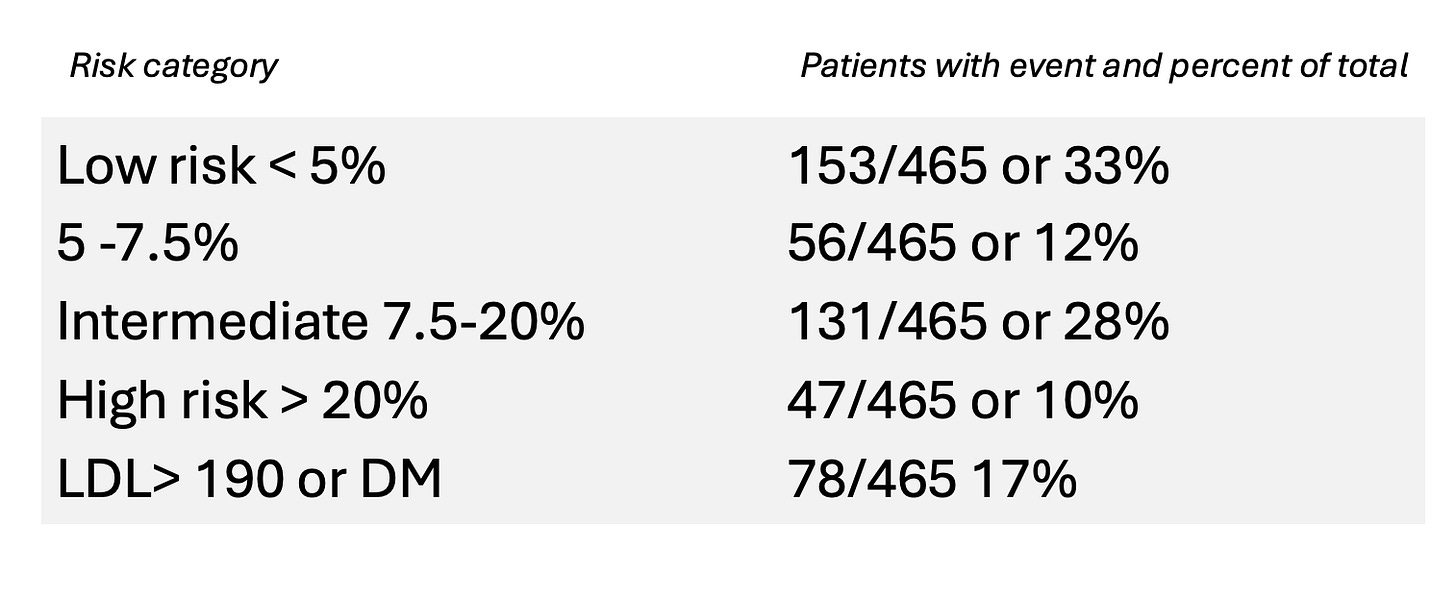

JACC published the look back study. The authors reviewed the risk scores in 465 patients less than age 65 who had their first MI.

The goal was to characterize how well standard risk scores and symptoms reliably identify patients at risk for a first MI event. The teaser is not very well.

The study is elegant in its simplicity. They had the clinical information in these 465 first MI patients. They then tell us the distribution.

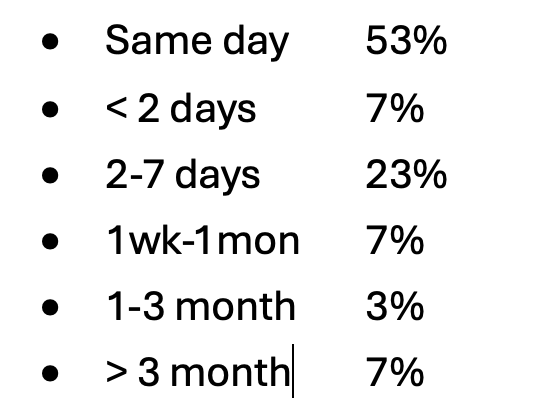

Here was the event rates based on timing of cardiac symptoms

Authors’ Conclusions

They noted that using the basic risk calculator, preventive treatment with statins was not recommended in 45% of patients who had their first MI. (Not recommended because calculated risk was < 7.5% over 10 years, which is the threshold that experts feel warrants medical treatment.) It’s remarkable—almost shocking—that one in three people had such low predicted risk.

And nearly 2/3rds of people who had their first MI had symptoms in only the first 48 hours. More than half had symptoms only on the day of the event. IOW: no real warning of trouble.

Lessons on Prediction

The main reason I like risk scores is that they incorporate more than just cholesterol numbers. Too often, a patient shows me their cholesterol numbers and says their doctor receommeded a statin, but he or she did not go over the total risk. Cholesterol is only one risk factor for heart disease. The classic example is a young healthy women with isolated high cholesterol; this person could have a high LDL-C but a super low 10-year risk based on young age, and lack of other factors.

Yet that table above shows that our risk scores are pretty bad. Namely, while low-risk individuals have a small percentage chance of having an MI, there are so many people in the low-risk category that they contribute a large absolute number of heart attacks.

As the authors note, “the large denominator of low-risk, asymptomatic individuals means that even a small percentage of events in this group results in a considerable absolute number of MIs.”

This is the MI paradox.

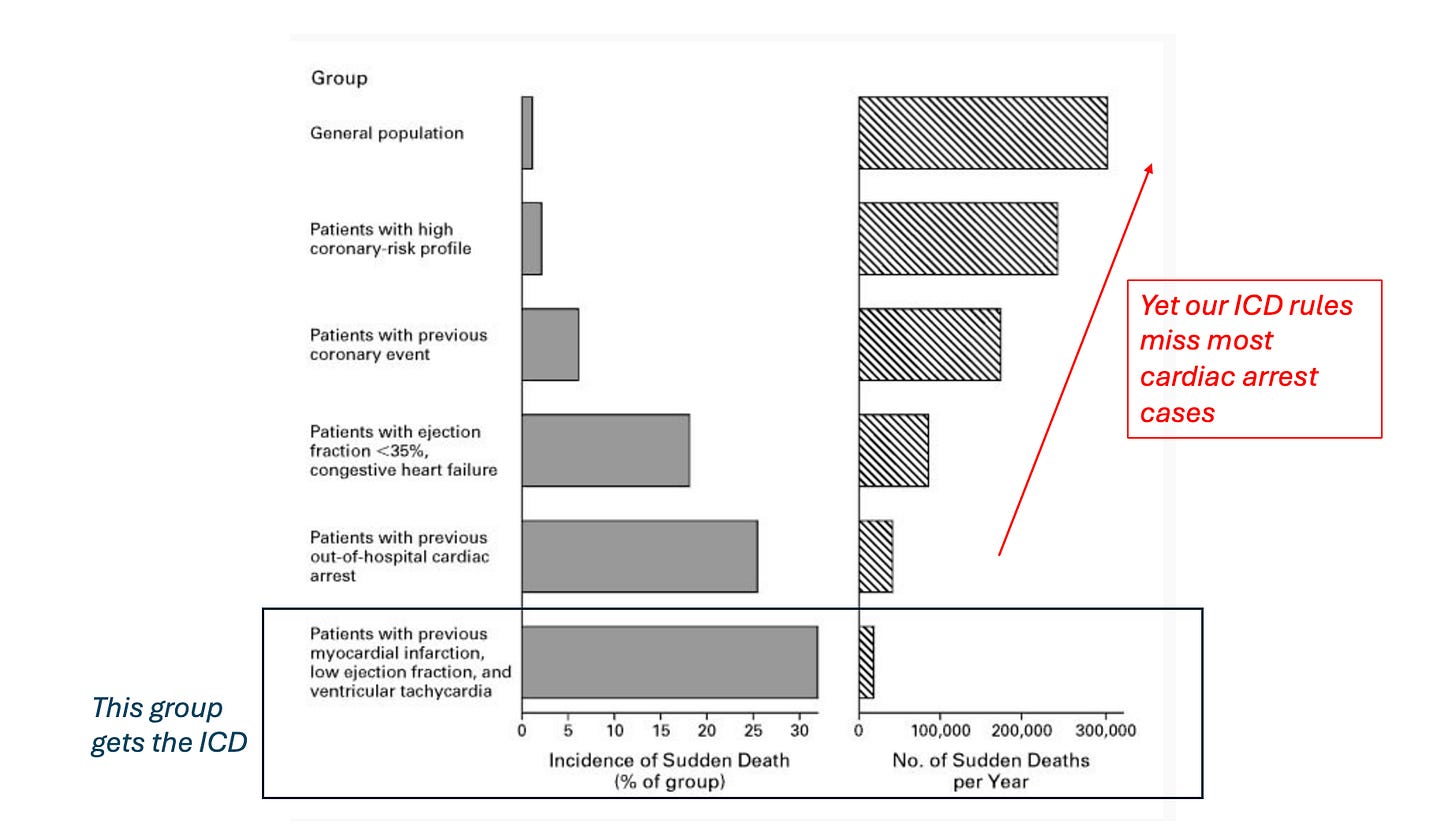

There is a similar paradox in the matter of internal cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) usage to prevent death from cardiac arrest. Here, we can identify high-risk people who have low ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure symptoms. The seminal trials showed that an ICD improved survival over medical therapy alone. That is why we use ICDs in these patients—though this needs to be retested in new trials.

Yet the problem for doctors and patients is that the vast majority of cardiac arrest cases occur in lower-risk individuals without HF or known heart disease.

The picture below is from a classic NEJM paper (Myerburg).

You could draw the same picture for MI and risk calculators.

The NY authors’ propose imaging as a possible solution to the paradox. They suggest (as do others) that detecting early atherosclerosis—the disease itself—may offer a more effective and personalized approach to treatment.

I doubt imaging will add much. This link goes to a calculator that incorporates coronary artery calcium. Proponents say adding in your CAC score enhances risk estimation. You can try it if you have a CAC score. What you will find it is that adding CAC adds little over-and-above the basic equation. And it still leaves the paradox where most people who have first events have lower risk.

What about actual coronary angiography? Surely knowledge of the degree of disease will enhance risk prediction. Well, not so much. Here is a study I will cover in the future showing that even coronary CT angiography only modestly enhances risk prediction.

The Future

Perhaps you think I am a nihilistic luddite. Get real Mandrola. Coming soon are genetic scores, inflammatory markers, and artificial intelligence.

Some tech wizard will design an app that combines all this. It will then tell us who will have an MI. And when it will occur.

Cardiac prevention will be transformed. The days of not knowing when an MI will occur will be forgotten—like the days of the rotary phone and three channels on TV.

The Reality

I am happy to be wrong, but I doubt this ever comes to be.

Cardiac disease is too complicated and too unpredictable. Nearly everyone over the age of 65 has some degree of atherosclerosis; what (exactly) makes that stable plaque become unstable will likely never be knowable.

The best we can do now is recommend healthy living, not ignore symptoms and fund medical education so that there are always available clinicians who have the skills to fix MIs when they occur.

The incidence of heart failure from ischemic heart disease has fallen dramatically because my colleagues have become so good at stopping a heart attack with a stent.

This is a wonderful thing. To me, improving access to this life saving procedure will bear more fruit than the quixotic quest to predict and prevent all heart attacks.

I am a retired cardiac nurse/echocardiographer. As you say, the heart and its pathologies are extremely complex. One observation I made over and over is that statistics are really not that helpful for an individual. I don’t think that’s because we don’t have enough data or studies, I think that’s because we place too much weight on our vain hope that we will be able to prevent all disease. We never will. Luck is always a factor, and also the unique response of the individual to their risk factors. I see coronary plaque as a kind of scab on the site that life creates in our coronary arteries. Some scabs are stronger than others. I don’t think we’ll ever really know why, and we shouldn’t believe that we will. Managing risk factors is an entirely different enterprise than treating unstable plaque. Management is about living well, intervention is about preventing imminent death.

Studies should continue, understanding should deepen and grow, but don’t fool ourselves or the patients that we are keeping them safe from MI by managing their risk factors. MI is largely unpredictable, and probably always will be. All of us can improve our health, but none of us can be safe from all disease. Let’s be honest about our goals and how little control we actually have over disease. Then we can work together to make life less painful with less debilitation, while maintaining a healthy respect for the power of Mother Nature. And as you say, have the interventionslists on standby to do their life-saving work when plaque ruptures, which is not a failure of risk management, it’s just plain bad luck.

Jonn,

You fell for the traps that most lay people fall for. First of all, I consider nonfatal MI’s a good thing! It tells you the guy really has a disease and we go after him diligently. A non-fatal MI doesn’t kill you. It just is a shot over the bow.

Always look at the denominator. There’s a lot more lower risk people than there are high risk people ego they’re going to get a good number of first MI.

Americans, even physicians, have been sold this bill of goods that we can prevent everything. It’s a faced lie. Always look at the number needed to treat and the significant side effects of our “treatments”“Youse pays ur money and youse takes ur chances.”

Preventive stents? Hasn’t that idea been disproven? COURAGE,ISCHEMIA.