Prevention is a challenge in younger patients; it’s near impossible in older patients

Yet another study reveals the challenge of mechanical stroke prevention techniques, such as left atrial appendage closure, when applied to older patients

The problem with trying to help older patients with one problem is that they often die of something else. Specialist doctors, like me, tend to forget this obvious fact.

We see a heart problem and forget that our patient is more likely to die from a fall, or cancer, or dementia, or pneumonia, than a stroke or heart attack.

So we begin the 2026 Study of the Week series with yet another example of how being old makes it hard to benefit from preventive procedures.

The setting is a large hospital on Cape Cod Massachusetts, a place with a high concentration of very old people.

The group of authors set out to describe their outcomes in 342 patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had left atrial appendage closure (LAAC), specifically looking at those greater than 85 years old.

It’s a simple descriptive study. They first showed that doctors at Cape Cod hospital were skilled at doing LAAC. Success rates were 98.5% and complication rates were only 0.3%.

About 1 in 4 patients (n = 89/342) who had LAAC were >85 years old.

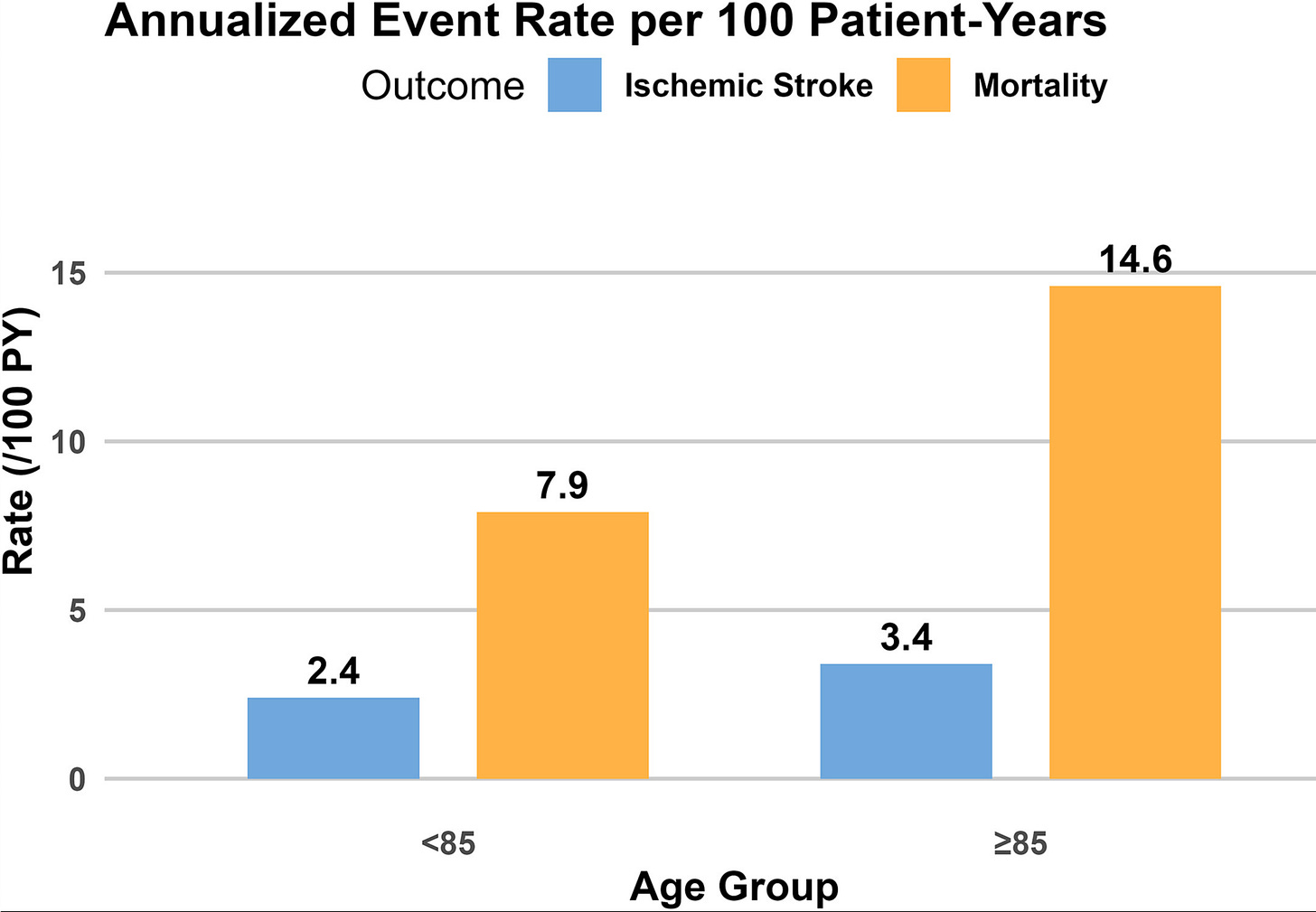

This key graph depicts stroke and death rates at one year after implant.

The takeaway is that chance of death far exceeds the rate of stroke—in both groups but especially in the older group.

Recall that stroke and bleeding are the only outcomes affected by left atrial appendage closure. The idea being that plugging the appendage can reduce stroke and reduce bleeding (by removing anticoagulation).

This graph shows that nearly 1 in 10 patients in the younger age group and 1 in 7 in the older age group were dead at one-year. The picture also shows that death is far more common than stroke.

Comments

This observation from Cape Cod is similar to an international all-comers’ observational study (n = 807) published in 2022, which also found that 1 in 6 elderly patients who had LAAC were dead at one year.

The Spanish authors wrote clearly:

As a preventive procedure, the benefit of LAAC grows over time as more adverse events are prevented. LAAC in patients that died within the first year of implantation could be considered as futile.

I could not agree more. Even if you felt that LAAC had a net benefit in patients (I don’t), your patient has to live long enough to accrue fewer stroke or bleeding events.

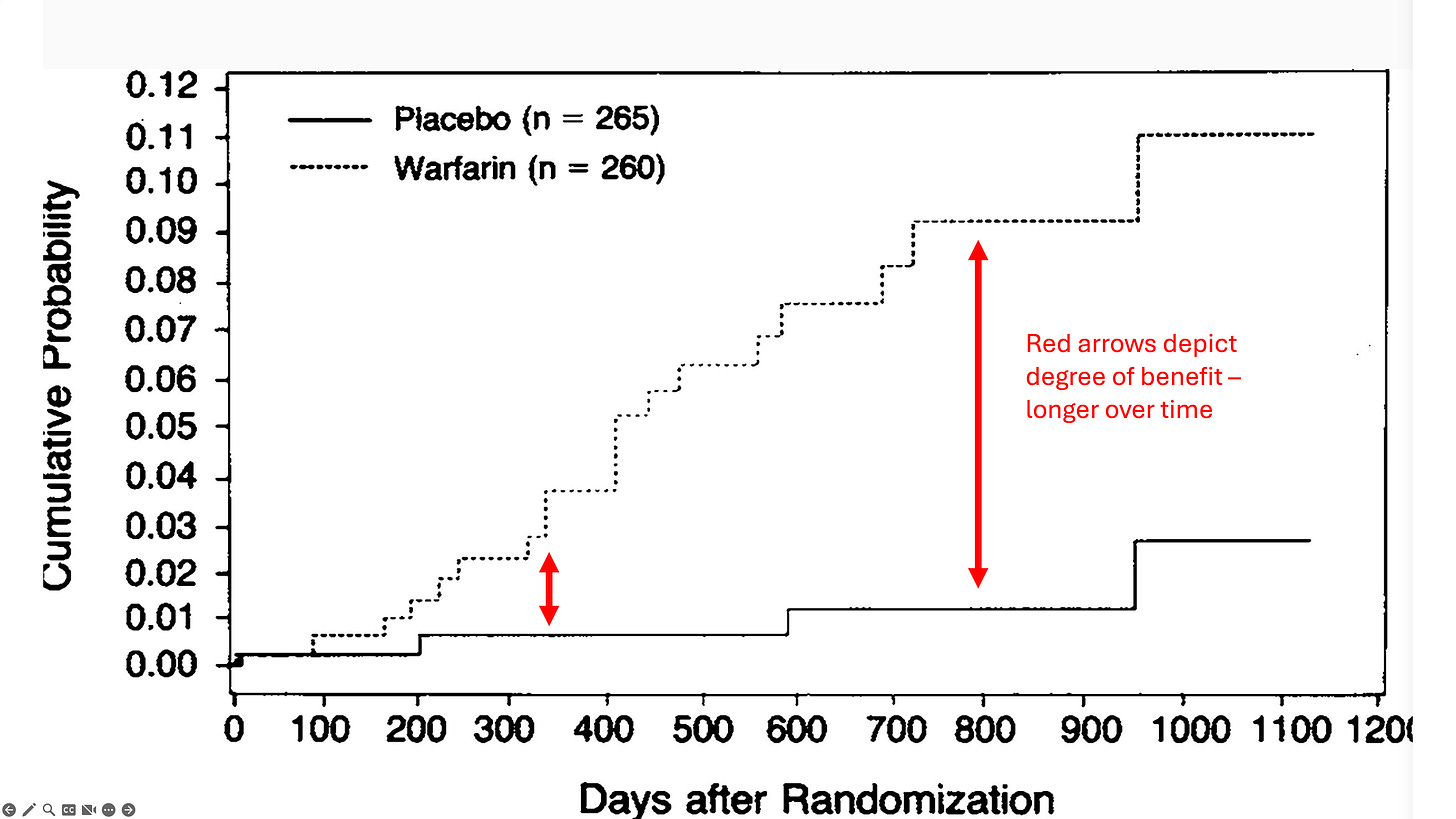

Patients with atrial fibrillation take anticoagulants to prevent stroke not over the next few days, but over the next few years or decades. It’s the same idea with left atrial appendage closure. Stroke prevention techniques require time to provide a net benefit.

The picture shows how time enhances benefit of stroke prevention in the SPINAF trial of warfarin vs placebo in patients with AF. Note the difference in event rates at one year vs 3 years.

The simple message is that older patients benefit a lot less from preventive treatments—mainly because they don’t live long enough to benefit.

This is not sad nor bad; it is a fact of nature. We give this observation a fancy name— competing causes of death. Recognizing it simply requires mastery of the obvious.

You may ask—as many do after I speak about the lack of benefit of LAAC—what should we do with those older patients with AF who cannot take oral anticoagulation because of bleeding?

My answer is not to put a foreign body in their heart but to simply not give them the anticoagulant.

Until a clinical trial shows benefit in this patient group doing less is surely more. Three words ring true when considering prevention in the elderly: resist the urge.

1. First, do no harm.

2. Starkly different from ‘Never let a billing opportunity go to waste’.

Too often, 1<2. Thanks for this article.

Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

That’s been one of my practice principles since day 1. It’s something that unconstrained practitioners seem to forget (or perhaps never learned).