Screening Colonoscopy Misses the Mark in its First Real Test

In today's Study of the Week, Vinay and I offer commentary on one of the most important trials of the year--the NordICC trial of screening colonoscopy.

There are influential trials, and then there are trials whose results threaten an established and highly lucrative norm.

On Sunday evening, The New England Journal of Medicine published results from the first randomized trial of screening colonoscopy.

The NordICC trial set out to test whether being invited to screening colonoscopy reduced the risk of getting colorectal cancer or dying from it. The primary endpoint was colorectal cancer incidence and death due to colorectal cancer. A key secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Pause here. Sit down. Before we tell you the results, think about the boldness of this question.

In the US, millions of healthy older adults have their colons visualized in the hopes of cheating death from one of numerous types of cancer. In many hospital systems, patients can sign up for this procedure without a doctor’s order. Screening colonoscopy has morphed into a rite of passage into middle age.

Background

Before NordICC, colorectal cancer screening was among the preventive interventions with the surest footing. Fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) had consistently shown a reduction in death from colon cancer–though it consistently failed to show any reduction in death from all causes. Flexible sigmoidoscopy had shown both a reduction in colorectal cancer death and death from any cause. Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) leveraged the principles of FOBT, but did not have direct evidence. Fecal DNA leveraged FIT testing. Blood-based screening had weak data, and colonoscopy– the mainstay of US practice– had no randomized data at all.

Before NordICC, the USPSTF endorsed the policy that any screening test was better than no test, but we quibble with that. Flexible sigmoidoscopy had the strongest data and should have been prioritized. But clinicians favor colonoscopy because it makes logical sense to look at the entire colon (akin to mammography on 1 breast), and, of course, because colonoscopy is well reimbursed.

Enter the NordICC trial.

Results

Slightly less than 85,000 patients were enrolled in NordICC in Poland, Norway, and Sweden. The results were clear:

Over 10 years of follow-up, an invitation to screening colonoscopy modestly reduced the risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer, but it did not significantly reduce the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Survival from cancer was nearly identical in both groups. And all-cause mortality was the same.

The specific numbers of the primary outcome:

The chance of getting (diagnosed with) colorectal cancer in the invited group was 0.98% vs 1.2% in the usual care group. This represents an 18% reduction in relative terms, and an absolute risk reduction of 0.22% or 22 per 10,000.

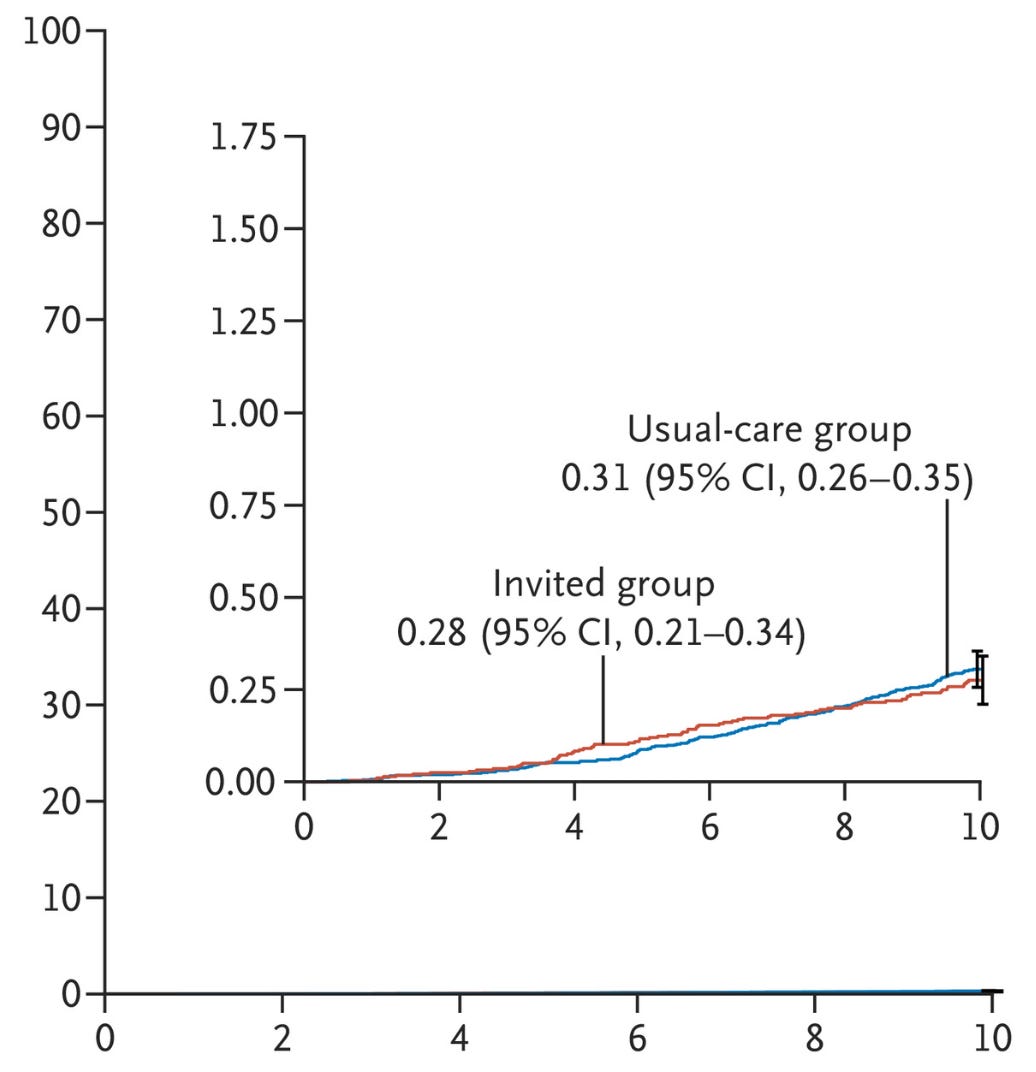

The chance of dying from colorectal cancer in the invited group was 0.28% vs 0.31% in the usual care group. This 10% reduction in relative terms amounted to a difference in 3 in 10,000 and did not reach statistical significance.

In the invited group, 11.03% of patients died; in the usual care group, 11.04% of patients died.

These top-line results led the editorialists to write:

This relatively small reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer and the nonsignificant reduction in the risk of death are both surprising and disappointing…

Now to the Nuanced Results

When the trial began, there were few if any organized colonoscopy screening programs at a population level in these countries. This is an advantage because it meant that the control arm had nearly no contamination– a commonly noted limitation in the PLCO trial of prostate cancer screening using the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test.

The NordICC trial tested the benefits of a widespread screening program vs. no screening. Persons in NordICC were randomized before they were asked to participate in a trial. If you were randomized to the invited group, you had to decide if you would have the procedure.

Less than half (42%) of those in the invited-to-screening group actually had a colonoscopy. That observation underpins the main criticism of the trial: you can’t benefit from a colonoscopy if you didn’t have it.

We offer two rebuttals to this argument:

First is that their seemingly low rate of acceptance after screening is not that different from the US experience. Current surveys suggest that 60-70% of Americans get screened for colon cancer. This rate has moved upwards in recent years. Although a rough estimate, it’s not entirely dissimilar to the rates achieved in NordICC, and close to the rates achieved at one accrual site—Norway, which did not report different outcomes. In our mind, NordICC applies reasonably well to current US practice patterns.

The second rebuttal gets into the weeds of trial conduct and statistics. While the idea of counting only those who have the procedure makes theoretical sense, it’s actually complicated. The authors did what is called a per-protocol analysis in which they look at those who actually had the procedure vs the usual care.

In statistical circles, purists believe trial results should be based on the group you are randomized to, and not what happens after randomization. This is called the intention-to-treat principle, or in this case, the intention-to-screen principle.

Why? Because the purpose of randomization is to balance known and unknown confounders, to equilibrate outcome distributions in the absence of an effect. A per-protocol analysis undoes randomization. People who follow through with colonoscopy screening might be different than those that shrug. They may be richer, or more likely to engage in other health behaviors, or more docile and compliant. In fact, if you are going to rely on per-protocol, why randomize at all? The authors adjusted for covariates in their per-protocol analysis; they could have just done this in an observational dataset.

Yet, with all these limitations, the per-protocol analysis (the best-case scenario), found that the risk of death from colorectal cancer was 0.15% in the invited group vs 0.30% in the usual care group. This is a 50% reduction in relative terms. In absolute terms, the risk difference is 0.15% or 15 per 10,000.

Three Areas to Comment On

I - Population vs Individual Benefits

NordICC investigators aimed to quantify the benefits of a population-based colonoscopy screening program. This is a relevant question because screening programs (in the US) are the norm, and their costs run into the billions.

Patients see ads from the lay press, from their hospital systems and from famous people. The core belief of these programs is that colonoscopy improves population health.

This trial upends that belief. Despite randomizing more than 80,000 individuals and following them for a decade, NordICC did not show a significant reduction in death due to colorectal cancer or overall death.

We believe this trial should result in the USPSTF and payers prioritizing flexible sigmoidoscopy over colonoscopy, pending the ongoing RCTs. Flexible sigmoidoscopy has better data and does not require deep sedation.

II - Individual Benefits

While the conclusions of NordICC pertain mostly to screening programs, its results also inform individual decision-making.

A person who decides to have a colonoscopy incurs substantial burden. The “prep” (which is a euphemism for pooping 12+ times) takes up a large part of the day before the test and then the next day is unproductive due to the procedure and its sedation.

Burden would be fine if there were commensurate reductions in risk. A person thinks: what are my odds for avoiding a colorectal death with and without the procedure?

The risk reduction in NordICC (the per-protocol analysis) was 0.15% over 10 years. This is incredibly small. Consider 10,000 people who have a colonoscopy: 9,985 incur all the burden and costs and get no benefit.

Then there is the matter of survival. It’s easy to forget that the point of being screened for any disease is not to avoid one of hundreds of maladies; it is to live longer.

NordICC data are clear: your risk of dying over 10 years was 11.03% without an invitation to screening and 10.88% with the procedure (that assumes the biased per-protocol effect size). We think most people would say it isn’t worth the diarrhea from the prep.

III - Colonoscopy vs other modes of colorectal screening

There are other modes of screening for colorectal cancer.

Fecal occult blood tests have shown modest reductions in death due to colorectal death but it does not reduce overall death rates. The advantage of FOBT is that it is an easy and non-invasive test.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy, which evaluates only part of the colon, and can be done without sedation, has resulted in statistically significant reductions in death due to colorectal cancer, and, in pooled-analyses, modest gains in overall survival.

Fecal immune testing (FIT) and fecal DNA testing have not been studied in randomized controlled trials.

The NordICC trial should be interpreted relative to these other less invasive and less costly means of colorectal cancer screening, which have delivered positive results.

It makes sense that seeing the whole colon during a colonoscopy would be the best screening test. The analogy to screening only one breast for cancer might be misplaced. The left and right breast are biologically similar, but the right and left colon are drastically different.

What’s more, the history of medicine is replete with examples of trials that overturn interventions that made sense. And so it goes here.

Final Caveats

All trials, and NordICC is no exception, measure average effects. In the same way that some individuals may benefit from a drug or device that failed in a clinical trial, screening tests can save a life. One person may have a cancer detected that can be treated. That is not up for debate.

What we need trials for is to produce an average effect in average individuals. That’s how we know about harm-benefit ratios and which interventions to recommend to our patients.

Average effects, however, don’t apply to everyone.

For instance, individuals with a strong family history of colon cancer have a higher baseline risk and this may increase their chance of benefiting from screening. Yet we still need more research about harms in this group. NordICC does not apply to these individuals.

Finally, this is not the end of colorectal screening trials. We will learn more from a Swedish study comparing colonoscopy against fecal immunochemical testing or usual care. And there are 2 ongoing US studies that will shed clarity.

For now, though, these are stunning results that should have immediate influence on decisions regarding screening programs and individual choices.

P.S. For more detailed information, Vinay has this 30-minute video explainer

I’ve always questioned the colon prep and here’s why. It has more and more been found that a healthy gut microbiome is important in a myriad of ways, not the least of which is mental health outcomes. What is the downstream affect of the disruption of the microbiome, especially in those who wind up having it done every 1-2 years.

There’s a study,

What about the people who:

1. Are injured by the procedure?

2. Are injured or die from the anaesthetic?

3. Are financially injured by the costly and needless procedure...were do I go to get a refund?