Should I Change My Mind About Aspirin for the Prevention of Cardiac Events?

The Study of the Week explores a provocative analysis of aspirin trials. I may have been wrong about preventive aspirin

Studies that tempt me to change my mind are worth telling you about.

The story this week centers on the use of aspirin for prevention of cardiac events in people without heart disease. I used italics because this story ONLY applies to people without heart disease—so called primary prevention.

In 2018, the NEJM and the Lancet published three trials that randomized tens of thousands of patients without heart disease to either low-dose aspirin or a placebo. ASPREE studied older people; ASCEND studied patients with diabetes, and ARRIVE studied patients deemed to be at higher risk of heart disease. The main question of these studies was whether aspirin reduced the rate of future cardiac events, without increasing the rate of bleeding.

The gist of the results is that aspirin used for primary prevention provided no net benefit. ARRIVE and ASPREE did not report statistically significant lower rates of cardiac events. ASCEND reported a 12% reduction in cardiac events but a 29% increase in bleeding.

These three trials strongly argued against using aspirin for the prevention of future cardiac events—in an average patient.

For me, though, I am specialist and most often see patients already on aspirin. In the absence of heart disease, based on the 2018 trials, I had recommended patients stop taking aspirin. But most of the patients enrolled in these trials were not taking aspirin before the trial.

The question for today is: Is stopping aspirin the same as not using it in the first place?

A new study published last week suggests that the answer is complicated.

Led by John McEvoy at the University of Galway, three other authors used data from two of the big 2018 studies. (The ARRIVE trial excluded patients taking aspirin at baseline).

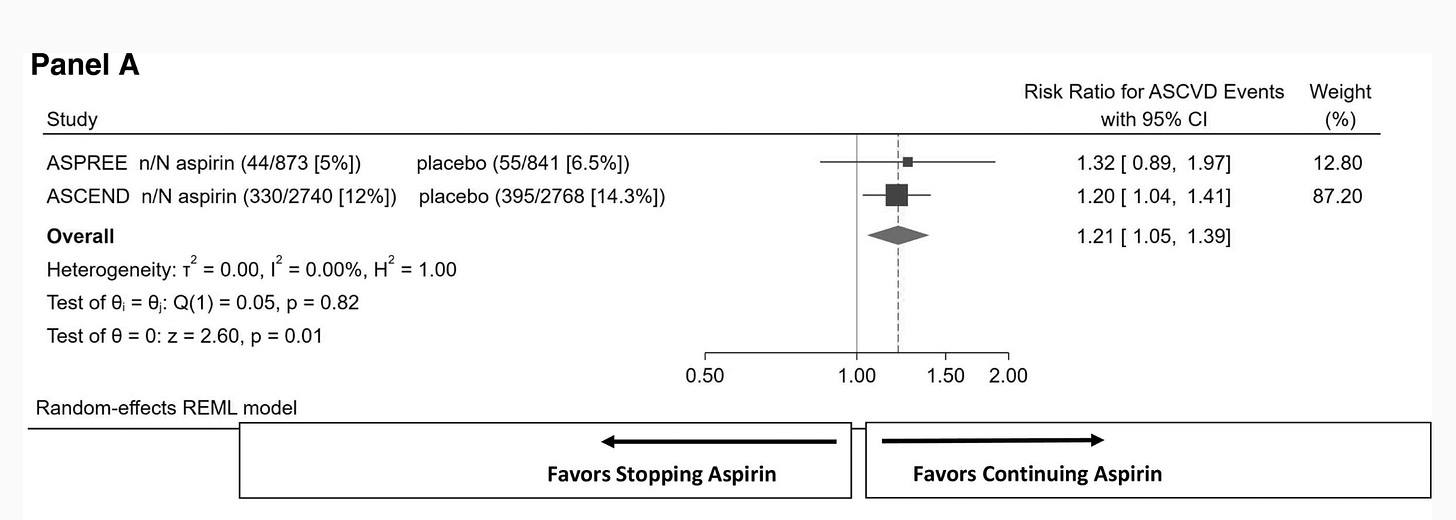

Specifically, McEvoy and his team were interested in studying the 15% or 7222 patients who began the two trials while taking aspirin before being enrolled. Half that group were randomized to remain on aspirin and half were taken off and put on placebo.

The results are below. In this subgroup of aspirin users, there was a 21% higher risk of cardiac events in the placebo arm. The 95% confidence intervals ranged from 1.05-1.39.

The authors also did the same analysis for major bleeding and found no statistically significant difference. In aspirin users, there were 14% fewer bleeds in the group who stopped aspirin and went on placebo. (Risk Ratio 0.86 (0.68-1.10) but the confidence intervals were wide—suggesting lack of precision in this estimate.

Summary:

This is a tough call. The overall trial results suggest that there is no benefit to taking aspirin to prevent cardiac events. In fact, not only is there not a cardiac benefit, there was a higher rate of bleeding.

But. But. In the smaller subgroup of patients who were on aspirin, there did appear to be a significant increase in cardiac events from stopping the aspirin, without a clear increase in bleeding.

The tension here is twofold.

On the one hand, trials are powered to find signals in an overall population. And in this case, there was no clear signal of benefit. When you select out subgroups (here, 15% of the two trials), there is a risk of seeing noise rather than signal. Never forget the subgroup analysis of ISIS 2, where they found highly significant effects based on astrological sign—a clear indication of noise.

But on the other hand, patients who have been on aspirin may be different than never-users of aspirin. Patients on aspirin have shown that they have yet to have either a cardiac event or bleed. And it may be that stopping aspirin might convert that person into a high risk patient. That may be important because aspirin may benefit a high-cardiac-risk low-bleeding risk patient.

So Should I Change My Mind?

When I go to clinic this morning and see a patient on aspirin who has no heart disease, should I recommend stopping the drug?

Before last week I would have said yes. This new meta-analysis makes me question that recommendation.

The ultimate way to answer this question would be to do a proper deprescribing trial.

You take people on a drug and randomize them to continue the drug or take a placebo. That is different than analyzing a small subgroup from a large trial.

Until then, I guess we are back to Dr. Kaul’s recommendation:

I'd have a hard time recommending continuing a drug because of a wrong decision to start the drug in the first place. "You're now addicted (tolerated) to said drug, so let's keep it going." Same can be said of a hard core alcoholic: go cold turkey and see all manner of problems, so keep the booze flowing. Ditto for acid blockers and hypnotics. Perhaps a slow taper will be best course of all.

These studies are nonsense since they never take into account other life style habits. I will continue to use herbs to accomplish the same things without any health risks. Big pharma's goal has always been to get as many people as possible taking as many drugs as possible even if no real reason exists to be doing so.

Trust the doctor. No thanks. There are no drugs or chemicals that are natural for the body to use. That includes many vitamins and minerals. If you were to check out the MSDS (material safety data sheet) sheets for all the ingredients in an aspirin, you might be rethinking its use.