I met Dr. Karsten Juhl Jørgensen at Forward’s innovative “4words24” conference in April. I was struck by Karsten’s deep knowledge of the medical literature, critical appraisal skills, and thoughtful approach to decision making. Here is a brief video of him summarizing the talk he gave at the conference.

He reached out after the USPSTF published the new breast cancer guidelines. There has seldom been an article that fits better on Sensible Medicine.

Adam Cifu

A few weeks before the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) issued draft recommendations on breast screening, a news piece came out about a study on breast cancer incidence in young Canadian women. A worrying increase of ‘up to 45.5%’ had been observed, being particularly pronounced in women in their 20’s.

Sounds scary, right?

Two weeks before, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) had issued updated mammography guidelines. In a major change, they now recommend mammography screening for women in their 40’s. Earlier, they had recommended informed choice for this group. They, too, had observed an increase in breast cancer incidence in young women and this was one of three reasons for their change, the other two being new model calculations, and worry that young black women have around 50% greater risk of dying from breast cancer than other groups.

Yet, the draft guideline from the Canadian Task Force did not recommend that women in their 40’s get screened. What is going on?

The evidence for breast screening is getting old. Most trials are from the 1970’s and 1980’s. Since then, there have been major changes in our understanding of breast cancer biology, how it is diagnosed, and how it is treated.

Fortunately, there is less stigma associated with a breast cancer diagnosis today and more women seek help for symptoms earlier. Surgeons have discovered that more radical treatment is not always better, reducing surgery related harms. Radiotherapy has improved too and is more focused with lower doses, again reducing harms. But perhaps most importantly, adjuvant therapies such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (anti-estrogens) have been incorporated into care since the 1990’s.

These advances have collectively led to one of the greatest successes in modern medicine. Over the past 30 years, women below 50 years have seen their risk of dying from breast cancer cut in half. A truly remarkable achievement, especially in such a young age group with so many valuable years ahead.

We can say, definitively, that screening has not played an important role in this success. Because reductions, if a difference exists, have been greater in countries that do not screen women in their 40’s for breast cancer. The clinicians who treat breast cancer and the researches who dedicate their careers to improving breast cancer treatment deserve much more credit than they get.

There is a clear age-gradient in observed reductions internationally, with the youngest age groups having seen the greatest improvements, smaller reductions in the most commonly screened age groups (50 to 74 years), and the smallest reductions in older women (Figure 1). This gradient fits well with improvements in treatment, not with screening as a cornerstone of modern health care.

Figure 1. Breast cancer mortality rate per 100,000 women aged 40 to 84 years in Canada over time. Note that the y-axis is on a logarithmic scale and that the risk of dying from breast cancer increases more with age than it may appear. Data from the International Agency for research on Cancer.

That screening does not play as great a role as we have been told for decades may seem counterintuitive. We know that breast cancers detected at late stages have a much worse prognosis than those detected at early stages. But thinking that cancer we detect late would have the same prognosis as those we detect early if only screening had ’caught it early’ is an oversimplification. It rests on the assumption that all breast cancers represent the same disease at different stages of development. This assumption does not fit with modern understanding of cancer biology.

Cancer biology is complicated. We are dealing with a spectrum of disease with varying degrees of severity. Those we detect late due to symptoms more often have an inherently aggressive biology and grow fast, spread early, and are resistant to treatment. They are thus selectively those with a poor prognosis and their biology was determined from very early on. Detecting such tumors somewhat earlier is unlikely to change their prognosis, because screening cannot change their biology. Breast cancer exists in a continuous struggle with the immune system and many cancers are eliminated.

Unfortunately, the rate of growth of many cancers is faster at younger ages, including breast cancer. This means screening at regular intervals is less likely to catch them. Denser breast tissue in younger women also means mammograms are less likely to find cancers.

Model calculations, such as those underpinning the changed USPSTF recommendation, are based on assumed benefits. But, collectively, the least biased trials of breast screening did not show a benefit for this age group. Although this does not exclude the possibility that a small benefit may exist, the USPSTF recommendation does not fulfill criteria for evidence-based practice and I find this step away from official screening criteria deeply concerning.

But what about the increasing incidence of breast cancer in young women – surely that is reason for concern and for more screening?

Well, again, things are more complicated than you might think. Both the USPSTF and the CTFPHC recognize and quantify the most important harm of breast screening: overdiagnosis. This is when screening finds a lesion that fulfill the pathological criteria for cancer but are cancers that grow so slowly (if at all), that the person with this cancer would never have been diagnosed or died from the disease without screening. Why is that important? Imagine the fear, impact on quality of life, and the physical implications of getting a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Now, imagine everything this person and their family went through was unnecessary.

It is uncertain how many experience this, but qualified estimates are around 3 for every 1 that benefit from screening.

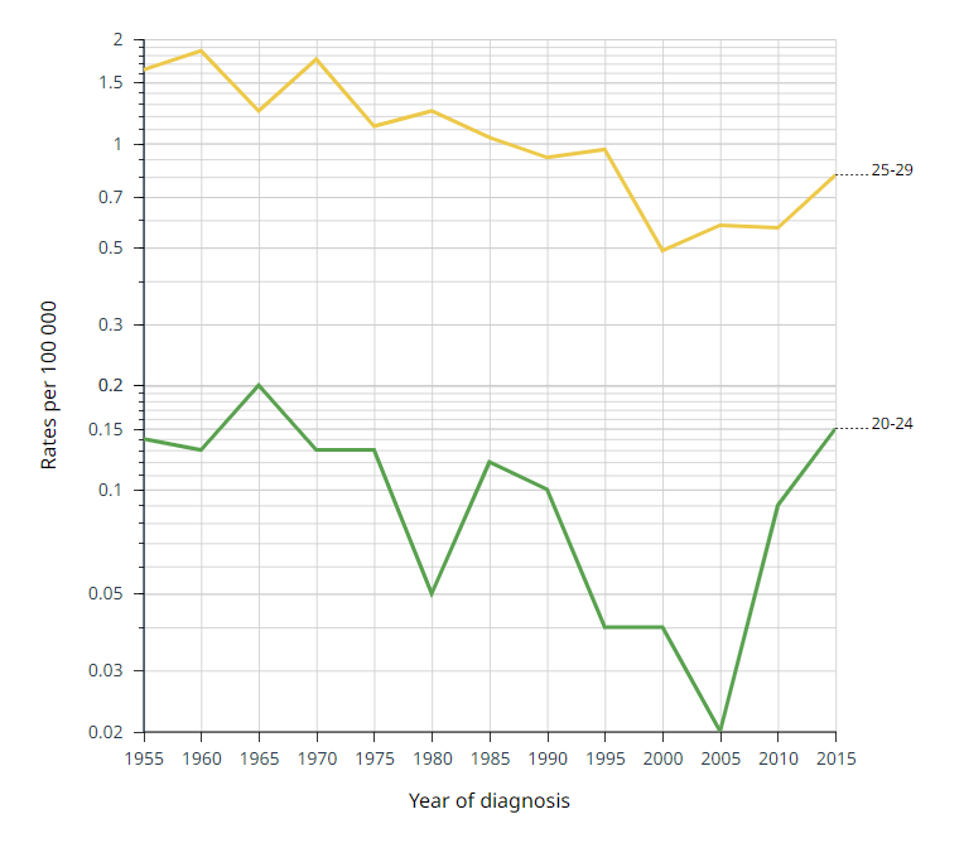

Overdiagnosis happens less often in young women and mostly with ’precursor’ lesions (DCIS). But there is a real possibility the observed incidence increases are partly iatrogenic, meaning caused by doctors and increased diagnostic activity. Neither the USPSTF nor the news piece mention this possibility, but the ’45.5%’ increase in women in their 20’s requires very few extra breast cancers because, fortunately, breast cancer remains exceedingly rare in this age group. In women 20 to 24 years, the risk of dying from breast cancer is literally one in a million (Figure 2). The increase was ’just’ 9.1% for women in their 40’s.

Figure 2. Breast cancer mortality rate per 100,000 women aged 20 to 29 years in Canada over time. Note that the y-axis is on a logarithmic scale. Data from the International Agency for research on Cancer.

Already before the new USPSTF recommendations, 85% of black women, compared to 78% of other women had been screened within the past 2 years. The fact that more black women are already getting screened argue against the idea that recommending more screening to all groups will solve the very serious problem of one group’s higher breast cancer mortality. Contrary, recommending screening for all young women is likely to aggravate the increasing incidence rather than reduce it. Making sure everybody has access to optimal treatment is more likely to reduce the concerning disparity in health.

Although it may sound like we are in the midst of a cancer crisis, the mortality data tell a very different, positive story: we are experiencing a triumph of modern medicine and there is less reason to start screening women in their 40s now than there ever was before.

Karsten Juhl Jørgensen is a professor of evidence synthesis and screening at Cochrane Denmark, University of Southern Denmark. He is co-author of a systematic Cochrane review on breast screening with mammography.

Thank you. Dr. Jørgensen essay was thoughtful treatment of issue.

Humans are not innately equipped to make sense of mortality risks w/ low incidence.

Fig.2 20-24 yro. Imagine urns of beads 2005 (2 red of 10 000 000) & for 2015 (15 red of 10 mil).

How many draws would you need to make to tell difference between urns?

I’m just here to say that mammography does not catch invasive lobular breast cancer, which is something under 1/6 of breast cancer. So if you feel a lump or a mass, get an ultrasound. Do it immediately. ILC tends to make strands that evade detection by mammography until it suddenly forms a mass, which can be large by that point. If this describes you, call your doctor today!