Skeptics

Even after 26 years on the Third Coast, I remain at heart a skeptical New Yorker. I think that is why I was quick to embrace the skepticism of critical appraisal when I first learned the skills as a resident. Not to date him, but David Rind was one of the faculty members who first taught me how to critically read the medical literature. In this essay he counsels us on when to moderate our skepticism and recognize that our understanding of an illness or therapy might need to change.

Adam Cifu

Lee Goldman used to talk about the difference between playwrights and theater critics as applied to research. Long ago I decided that I was better suited as a critic rather than a creator. Being a useful and constructive critic of research means identifying the strengths and weaknesses of studies. Like a theater critic who hates every play, a reader of research who reports that every study is flawed and pointless, is a nihilist, not a critic.

When we teach clinical epidemiology and biostatistics, we typically focus on the flaws that can lead to the wrong answer. As a result, many medical students and residents get the impression that the goal of reading a trial is a hunt for a fatal error. This can lead to doctors thinking that all trials are uninformative, particularly when those trials disagree with their prior beliefs. We all have some degree of intellectual conflicts of interest – we all like to be right – and so there can be a tendency to harshly interpret trials that seem to prove us wrong. We justify ourselves as being skeptics.

That is not a position entirely without merit. If prior beliefs were on a firm foundation, new contradictory evidence should often be less convincing than when it confirms prior information. But it’s important to recognize when that’s not the case.

Here is a famous example involving the interpretation of new evidence.

The year was 1993, and I was co-directing resident journal club at my institution. In the 1980s, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren identified C. pylori (soon H. pylori) and began suggesting that infection with this agent was responsible for most peptic ulcer disease. This was a radical departure from the accepted understanding of PUD – that PUD was due to excess acid in the setting of emotional distress. Studies showed that treating ulcers with regimens that included bismuth (often with additional antibiotics) had lower recurrence rates and that eradication of H. pylori dramatically reduced the risk of ulcer recurrence.

Arguments were made that maybe, because bismuth itself has protective effects on mucosa, the benefits were from those protective effects and not because it aided in eradicating H. pylori. These arguments were not very convincing given the body of evidence, but people were hesitant to change deeply held beliefs. Into this space came a randomized trial aimed at eradicating H. pylori without bismuth. One arm received ranitidine alone, while the other arm received ranitidine plus amoxicillin and metronidazole. The trial found greater healing in the antibiotic arm at six weeks (92% vs. 75%), dramatically lower recurrence at one year (8% vs. 86%), and dramatically lower recurrence in patients in whom H. pylori had been eradicated versus not eradicated (2% vs. 85%).

At a journal club at the time, I watched a group of 15 residents explain why the trial was not convincing. What if amoxicillin was protective against ulcer recurrence? What if metronidazole was protective? When I pushed back, I was informed that a senior, and much revered member of the GI department, thought the H. pylori hypothesis was bunk.

For those looking back from today, it likely seems ridiculous that people were so unwilling to accept these trial results, but it gets at this issue of always looking for the flaws in a trial. Here we had a trial specifically designed to respond to low-probability-of-truth objections to a prior body of evidence. The trial had shown exactly what you would expect if H. pylori was causative for ulcers, and yet people remained unable to abandon their prior beliefs.

I have recently been reviewing trials of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) as part of my work for ICER and have watched the debates unfold. In the Neurology community there are clearly those who, prior to the recent trials, believed or disbelieved that clearing amyloid would affect the course of AD.

Two nearly identical trials of the monoclonal drug aducanumab, ENGAGE and EMERGE, had disparate outcomes: ENGAGE showed no benefit and EMERGE showed that the drug slowed decline. The manufacturer (unsurprisingly) argued that ENGAGE was wrong. The believers agreed that EMERGE was the correct trial. However, when we reviewed these results, there was no convincing explanation for why these trials had disagreed. The believers thought that ENGAGE hadn’t treated enough patients with a high enough dose, but this made no sense when you looked at the trial results as a whole. The non-believers argued that there was more unblinding in EMERGE (due to adverse events -- ARIA). This also did not convince me, and I concluded (and still conclude) that we have no idea why these trials disagreed.

By the end of that battle, the camps were even more locked into their beliefs and were ready to be skeptical of any result that was contradictory. In late 2022 we learned that a large RCT found that the monoclonal lecanemab appeared to slow progression in AD. Skeptics argued that this was likely due to functional unblinding due to the side effect of ARIA. This seemed important to consider, and so we looked at whether outcomes in trials of monoclonal antibodies for AD correlated with rates of ARIA. There was no hint of correlation, and we concluded that unblinding due to ARIA was an unlikely explanation for the outcomes of trials of anti-amyloid antibodies.

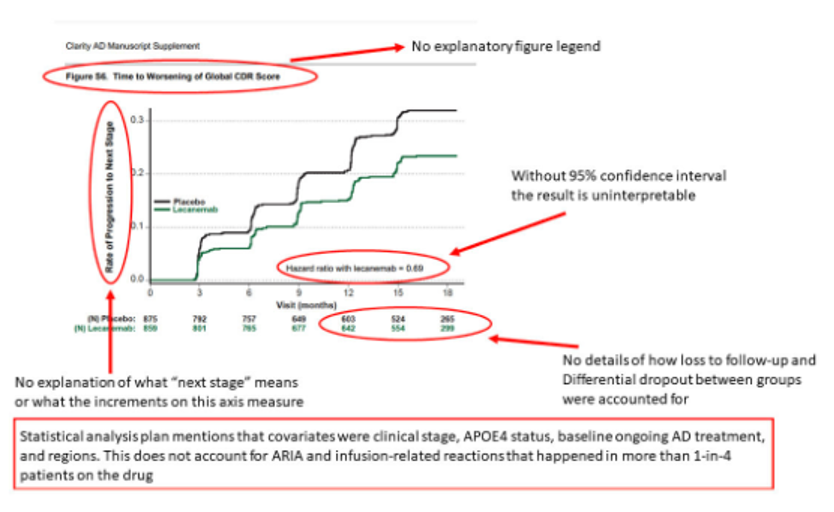

A number of attacks seemed to focus on this figure in the Supplement to the article on lecanemab and the “shoddy” editorial work of the NEJM for allowing it to be published:

Now, admittedly, this is not a very good figure. The y-axis is not explained as it lacks a definition of “progression to next stage”. But this is a figure in the supplement that does not pertain to a primary outcome. It was probably not a major focus of the peer reviewers or the editors.

Here is an example of a set of tweeted objections to this figure, presented (unedited) as red markup of the figure with explanations of the concerns in black:

I think these are the thoughtlessly critical remarks of a non-believer:

No 95% confidence interval: I’m sure it would be possible to calculate some kind of confidence interval on the circled hazard ratio, but the entire figure is looking at two different types of progression (from MCI to mild AD and from mild AD to moderate AD). This makes the results hard to interpret. This figure is not part of the primary outcomes of the trial and objecting to a lack of confidence intervals seems like something of a red herring; it is irrelevant to the interpretation of the trial whether this particular result has a CI that crosses 1.0.

Loss to follow-up: This concern is less reasonable. This is a KM curve, so the numbers at each time point below the figure show the number at risk for an event. The greater “loss to follow-up" in the placebo arm, at least up through month 15, is not that at all – it’s that more patients have progressed in the placebo arm, and once you have progressed you are no longer being followed for progression – you no longer count in the numbers at risk. This is typical censoring after an event in a survival analysis.

“Covariates”: The intended concern is unblinding due to ARIA, but also a new attack: that there was unblinding due to infusion reactions. Many more patients had infusion reactions with lecanemab than with placebo (26% vs 7%), so it’s a reasonable possibility to raise. However, the non-believers have been objecting that the trial didn’t present results stratified by presence or absence of an infusion reaction, as if the authors should have guessed that this would become a focus of concern.

If infusion reaction really caused important unblinding, you might expect that there would be a connection between that unblinding and measurement of clinical outcomes. It turns out that 75% of all infusion reactions happened with the first dose in the trial, and the majority of patients never had another infusion reaction. Think about what you would expect to happen to the primary outcome over time if you have a very early event (infusion reaction) that makes you think you are in the treatment arm, and then you have no additional events going forward. I would expect, a priori, that you’d see separation of benefit early after trial entry and then loss of separation later. Placebo effects usually lead to modest, short-term effects. In fact, the exact opposite is seen in this trial – the effect occurs late and increases with time.

We spend a lot of time teaching doctors what can go wrong with study and trial results, but it is also important that doctors recognize when a trial has really called into question a previously held belief. If a trial shows something very different from what you would have expected, it is worth searching for flaws that might explain the unexpected results. It is also worth considering that your previous understanding of the issue might have been wrong.

Both the amyloid believers and non-believers would do well to think about whether they are interpreting evidence objectively or are trying make trial results they don’t believe go away. The believers tried to make the ENGAGE trial go away, but even now, after the trial of lecanemab makes it more likely that an anti-amyloid therapy is effective, I see no good way to tell whether aducanumab does or does not work. The non-believers seem so convinced that they will ask authors to jump through hoops that would never be asked of a trial that supported their worldview.

It is good to be skeptical, but you also need to recognize when new evidence is likely correct. Every trial can be attacked on some basis post-hoc since no trial is perfect or able to address every concern. But despite that, you don’t want to find that you are the one arguing that amoxicillin directly promotes mucosal healing in the stomach as a way to discount the ever-growing body of evidence that PUD is an infectious disease. If you believe something is true and a result challenges that belief, remember to subject the evidence supporting your belief to the same degree of skepticism that you apply to the new result. The best theater critic occasionally admits to love the work of a director she once hated.

David Rind is an academic primary care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Chief Medical Officer for the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Prior to his work at ICER, he was Vice President of Editorial and Evidence-Based Medicine at UpToDate.

Appreciate the space to broadly reflect on my own biases. Thank you.

A very good dose of serious advice from David Rind. However, I do think that we should object firmly to the first sentence of the second paragraph: Note his chosen verbiage, ". . . .flaws that lead to the wrong answer". In biostatistical matters we actually never "uncover the right answer" and this startling point was made in a leading textbook some years ago by (I seem to recall) David Sackett (?) --- viz. in all applications of modern epidemiology sleuthing, including uses of even the most scrupulous RCTs, investigators will *always* get approximations of the Truth underlying some matter at hand. I think that epidemiologists sense reality through layers of fog, sometimes with greater difficulty than at other times, but never with 100.00 percent clarity despite strong applications of the most intense and au courant computational Kung Fu. In sum, I wish simply that Dr. Rind had said, ". . .focus on flaws that will lead the unwary to form misleading conclusions".