Staying True to Trial Analyses -- The Tale of Two Screening Trials

I contrast two population screening trials--DANCAVAS and NordICC. One stayed true to the principle of randomization. The other broke traditional intention-to-treat principles

When you randomize patients to two therapy groups, you must count outcomes based on the group that the patient was randomized to. It does not matter if the patient did not take the drug or have the procedure. The name we give this principle is intention to treat.

There is a temptation to count only people who actually get the drug or procedure. This is called the as-treated group. The problem is that patients who get the procedure or drug may be different than the ones who do not. Using as-treated outcomes breaks the balancing benefits of randomization.

Two screening trials exemplify these concepts. Both attempted to sort out a population benefit to screening tests.

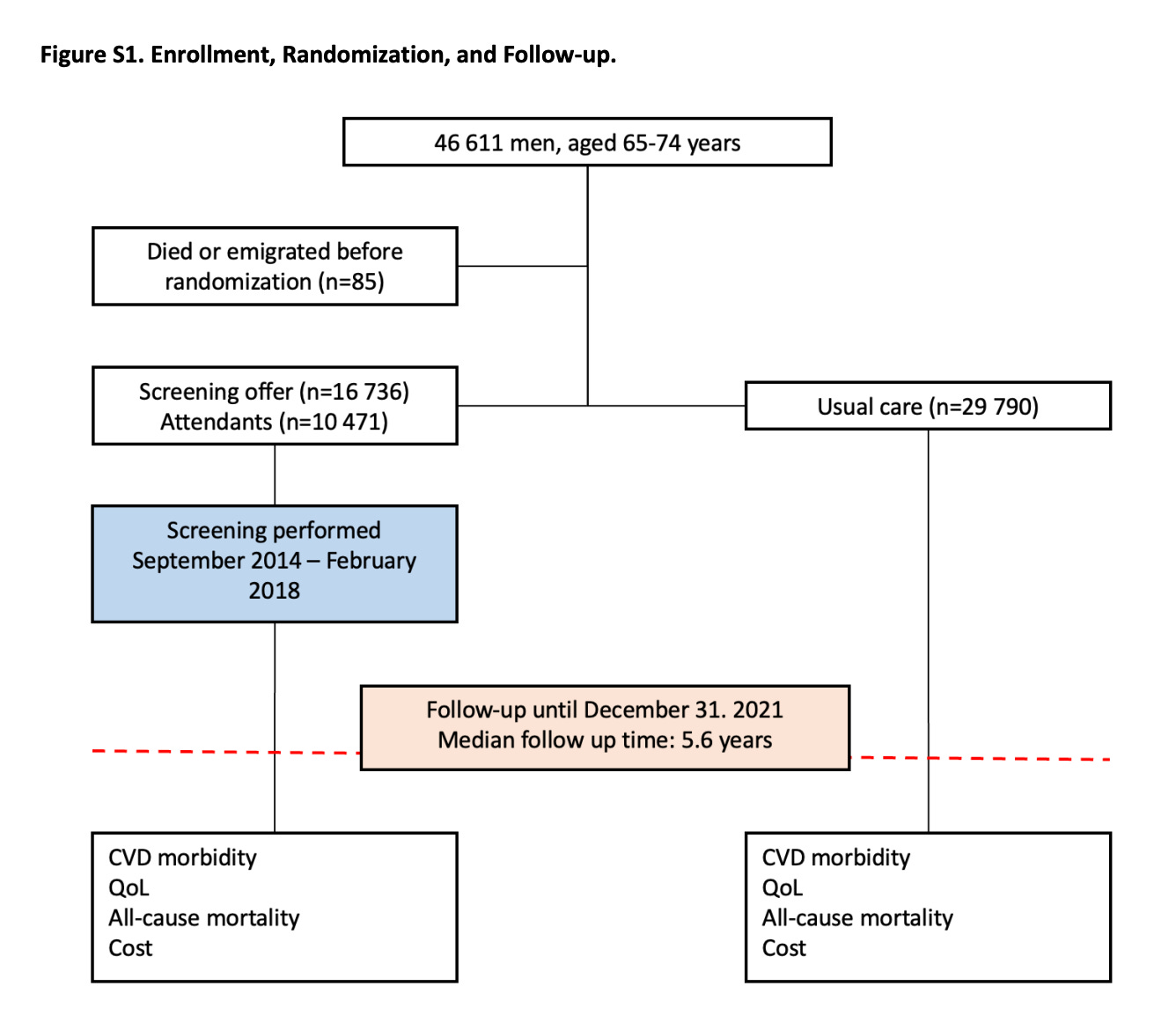

In the DANCAVAS trial, the intervention was an invitation to an efficient pragmatic cardiac screening program including blood, ECG and imaging tests. If that screening program identified an issue, action was recommended through the normal Danish health system. The control arm was people not invited to screening who received usual Danish healthcare. The trial endpoint was mortality. Alive or dead.

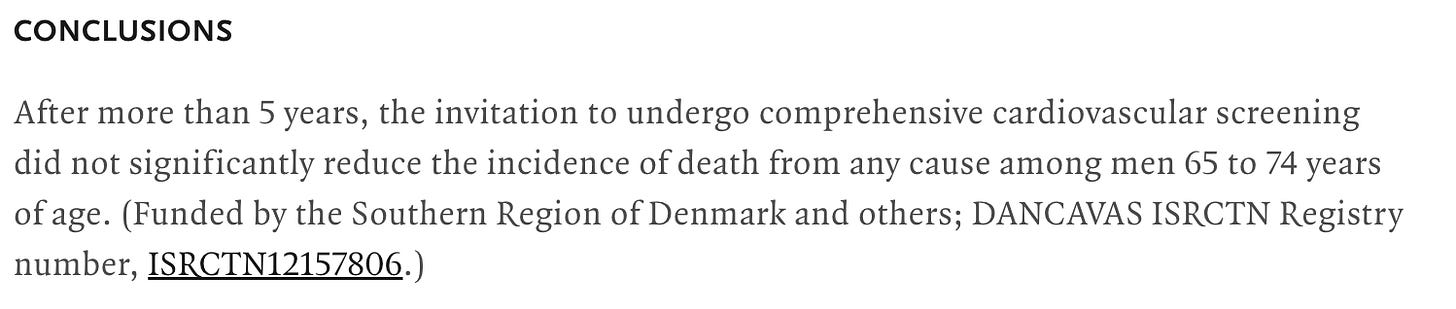

In the NordICC trial, the intervention was also an invitation to undergo colonoscopy screening (the invited group) or to no invitation and no screening (the usual-care group). The primary endpoint was the incidence of colorectal cancer and related death, and the secondary end point was death from any cause.

Trial Results and Interpretation

In DANCAVAS, screening was offered to ≈ 16,700 people and not offered to ≈ 30,000 who remained in the Danish healthcare system. Randomization was at the invitation letter level.

You can see that of the 16,700 invited, only 10,471 individuals attended screening, which means about 6300 patients did not attend screening.

The main result was that 12.6% in the invited group and 13.1% in the control group died (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90 to 1.00; P=0.06).

I quibble with this strict conclusion because the 95% confidence intervals allow for a 10% relative risk reduction in death, but, statistically, the trial did not meet significance.

My key point is that, to this day, 3 years on, DANCAVAS investigators have never reported the results of the people who actually got screened (N = 10,471) vs those who did not attend (N = 6300).

When the trial was presented in 2022, I asked senior investigator Axel Diederichsen why he did not present the “as screened” analysis, and he looked askance and said that would not be proper.

I understand it as not proper for two reasons: one is that DANCAVAS is a population-based test of invitation to the screening program. The second reason was that patients who decided to attend vs not attend likely have different baseline characteristics that would preclude causal inference from the intervention.

In the NordICC trial, ≈ 28,000 people were assigned to have colonoscopy and ≈ 56,000 were assigned to no screening.

Similar to DANCAVAS, a large fraction of individuals (58%) assigned to the colonoscopy group did NOT have the procedure.

Applying the DANCAVAS methods to NordICC yielded a death rate in the invited group of 11.03% and 11.04% in the usual-care group. The HR was 0.99 with 95% CI of 0.96-1.04. Solidly negative.

The risk of death from colorectal cancer (0.28% vs 0.31%) was also not significantly different in the invited vs usual care arms. (HR 0.90 (0.64-1.16).

So that’s it, right? Same results and discussion as DANCAVAS.

No. That is not what happened.

The NordICC investigators did not resist the urge to stay true to randomization. They presented the adjusted per-protocol analysis “to estimate the effect of screening if all the participants who were randomly assigned to screening had actually undergone screening.”

This analysis found a statistically significant 31% relative risk reduction in colorectal cancer and 50% reduction in colon cancer death rate (0.15% vs 0.30%).

When I mentioned NordICC to a GI colleague, his eyes brightened, and he told me that you have to get the colonoscopy to benefit.

This message, of course, came from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Talking Points memo pictured below.

Comments:

The point I hope to make is not about the merits of cardiac or colonoscopy screening.

My main point is to illustrate how one set of authors stayed true to their original analysis and did not even dare to present the as-screened analysis, while the other group of authors broke the rules of intention-to-treat.

Both trials set out to study the effects of population based screening. Does an invitation to cardiac screening or colonoscopy improve outcomes?

The intervention was not the screening tests but the invitation to screening.

This, I believe, is a relevant public health question. Because people who are able and willing to take the time to have these tests are different from people who cannot. Those differences could surely cause differences in outcomes.

I can’t speculate on the NordICC authors’ reasons for presenting the as-screened numbers. Perhaps it was the peer-reviewers that forced them.

But I, and surely you too, can speculate on why the AGA were ready with their talking points about the biased as-treated analysis.

Notice that AGA did not take the opportunity to educate the public about causal inference and randomization. They did not say that better outcomes were noted in the as-screened group because these patients were healthier, richer, or more health conscious than the non-screened group.

They attributed all the benefit to the procedure, rather than the potential differences in patients. Of course they did.

There are really four populations. (1) those invited who screened; (2) those invited who did not screen; (3) those not invited who screened anyway; (4) those not invited who did not screen. Population (3) is really the fly in the ointment. Then there are the sub-populations of (1) and (3) who detected illness (1/3 A) and those that screened that did not detect illness (1/3 B). It would be interesting to know false positives and false negatives in these two groups and associated outcomes, including adverse side effects. Why? You might discover, for example, that sending an invitation has no impact on screening rates, or maybe it does. You might also find that screening is ineffective in accurately diagnosing disease and that the side effects resulting from false positives overwhelms the advantage of finding the disease early, or the opposite. If you were actually trying to figure out what policy to adopt would this information be valuable? I think it would. Why invite people to an ineffective screening? Why invite people to a screening that is more likely to cause harm than to advance health? Of course, once you start the study you probably have little ability to modify it on the fly without injecting bias. So it is best practice to really think things through before you start and to challenge your assumptions. Maybe screening is ineffective. Maybe screening is effective. I suspect that the study designers started from the assumption that screening is effective. But that assumption may not be true. Whatever the truth was, it would impact the results of this study.

Actually, this is a simple topic. It becomes complicated if you don't understand randomization.

I made it complicated (including an error) by not adequately proof-reading and, originally by making the discussion too general. This is the revised version.

The problem is easiest seen with an example.

You are studying the effect of an antidepressant pill on a cognitive test like matching words. There are two groups, one who takes he pill and a control who takes a look-alike placebo. Both are randomized to relevant variables, age, health status, etc.

100 people are assigned to the the pill group. The outcome is that 30 people show a increase in performance on the test. You would report that people in the pill group have the measured increase. That's what we always did. The measured effect of being assigned to take the pill is an increase of 30 %.

However, you suspect that not everybody took the pill for whatever reason. The experiment is repeated with TV cameras and blood test for presence of the pill. It turns out that, for some reason, only 60 people actually took the pill. They included the 30 who has decreased performance, that is, 50% of the people who took the pill showed an effect.

This is called per-protocol, that is, the subjects did what you told them to do. You report that the drug is 50% effective. In addition, you report that there is only 60% adherence. Again, this is what we always did.

Now, what's odd is the appearance of the idea of intention-to-treat which says that, even if yo know that only 60 people took the drug, you must report the data as if all 100 subjects took the drug. It doesn't make any sense. It's, in fact, false and misleading.

Where did it come from? It doesn't make sense. The answer is that frequently all we know is how many people were told to take the drug and what the outcome was. We suspect people may have lost the pill or spit out or whatever but we don't know this so we have no choice to report the outcome as a fraction of all the people in the group. As in the example above, it's. what we always did because it's all we could do and did not give a name.

Intention-to-treat answers the question: what is the effect of being assigned to an intervention?

Per-protocol answers the question: what is the effect of actually following the intervention.

Usually, we are not interested in the actual assignment to the study group. The important part is, if we follow instructions, how will it turn out. Again, as the experimenter, we frequently don't have good access to adherence to the protocol. In this case, we have no choice but reporting the data we have.

The confusion is in understanding randomization.

Randomization is over before the experiment begins. If you are randomized, the outcome cannot affect the randomization. If you find out that subjects were not randomized -- e.g. they were smokers, but did not report that during randomization -- you have to do the experiment over.

Once in the study, you cannot be un-randomized by the outcome anymore than you can become un-baptized. You can become a bad person, or you can become excommunicated, or whatever, but you were baptized.

Intention to treat asks what is the effect of HAVING BEEN TOLD to follow instructions.

Per protocol asks what is the effect of following instructions, that is, what is the effect of the intervention. We discussed this in a blog post and a publication (link in the post).

https://feinmantheother.com/2011/08/21/intention-to-treat-what-it-is-and-why-you-should-care/