Study of the Week - Endpoints

Let's try out a new idea

Sensible Medicine will experiment with a way to help people understand medical science. Each week, or thereabouts, we will explain a study in short form. No more than 750 words. The point will not be the specifics of a study. That’s too narrow.

The point will be to highlight a key concept in critical appraisal. Sadly, most of these columns will highlight dubious maneuvers, but we will also show you science done well.

The grand idea is to improve science literacy.

Endpoints of a Study – The Story of the DIAMOND Trial

The topic this first week is changing endpoints of a trial.

In medical science, we often pit a drug or device against a control group, such as a placebo or the standard of care. A vital part of such a comparison is the choice of what to measure—the endpoint.

You must, and I mean must, choose this endpoint before the experiment begins. Once you look at the data, there’s too much of a temptation to focus only on the positive things.

In cardiology, we used to measure overall mortality. Death is a great endpoint because it is both important (obviously) and bias-free: a person is dead or alive.

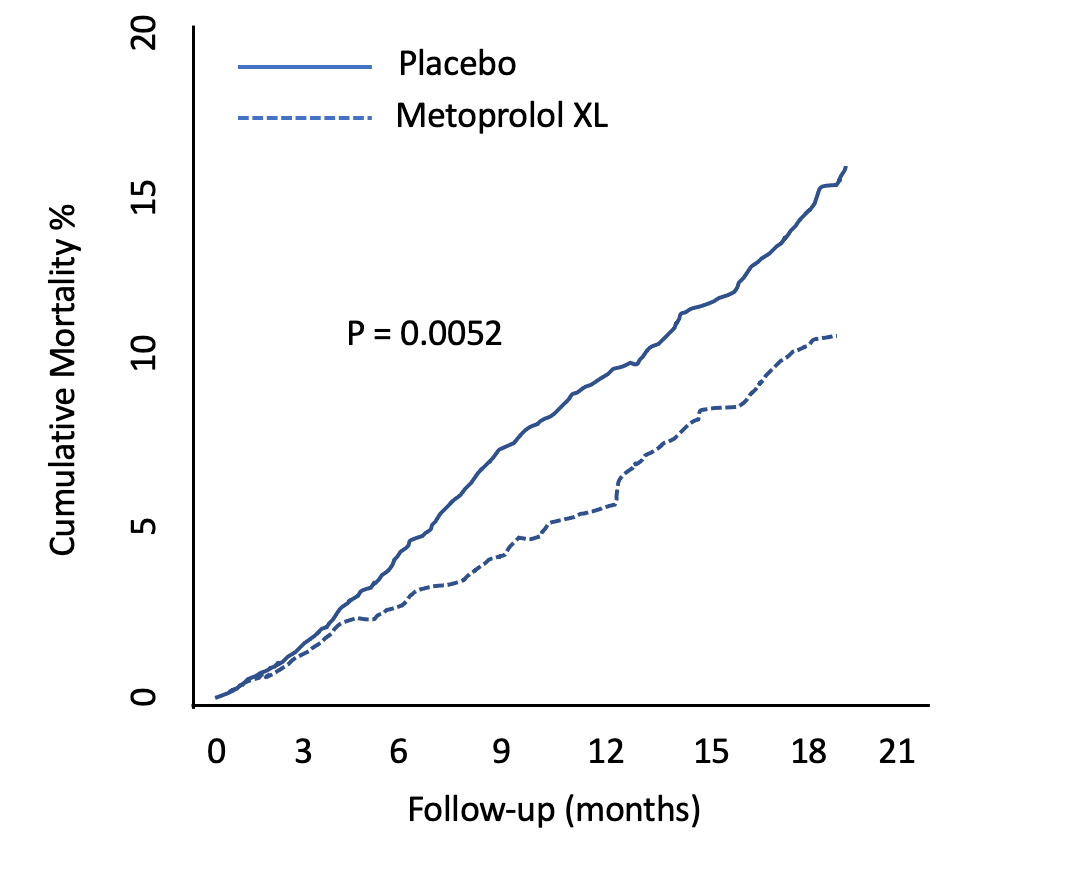

Look at metoprolol XL for heart failure in the MERIT-HF trial 23 years ago. The y-axis is death. (Nearly a 4% absolute risk reduction in death.)

Due to serious progress over the past two decades, extending life has become a very high bar in cardiology. That’s good news for society but bad news for the makers of new therapies.

It's become common therefore to see trialists use surrogate markers of efficacy. A surrogate endpoint is a substitute for a meaningful endpoint that’s expected to predict the effect of the therapy.

Surrogate endpoints come in different varieties; some are reasonable, say, a hospitalization, while others are ridiculously distant from anything a patient would care about, such as a lab value.

The DIAMOND trial studied the drug patiromer, which is a powder that a patient takes to lower potassium levels. High potassium levels can be deadly. The powder is mixed in water and swallowed; it binds potassium in the gut. Patiromer is already approved and costs about $1,000 per month.

Potassium binding might be a useful thing for patients with heart failure due to reduced heart function. That’s because two of the four classes of drugs that help patients live longer can cause high potassium levels.

The idea behind patiromer is that its use could allow patients to take beneficial drugs and thus live longer. I know; this sounds convoluted: a drug to treat a drug side effect. Yet it is a plausible thesis.

The company that makes patiromer, along with academic doctors, designed the blinded trial called DIAMOND. They started enrolling patients who had heart failure and high potassium levels. One group got patiromer; the other placebo.

Their plan was laudable; it is exactly how we learn if things work. The trial would measure two surrogate endpoints: death due to cardiac reasons or hospitalization for any cardiac condition. We call this the primary endpoint.

But we will never know whether the drug improves these outcomes.

That’s because the makers of the drug decided to change the study endpoints. Their reason was slow enrollment, lower than expected event rates, and the uncertainty of the pandemic.

I hope you are now wondering what endpoint they decided on. You want it to be something important. It is an experiment on humans after all.

Well, no, they decided to measure changes in potassium levels.

The drug is already approved as a potassium-lowering drug! This would be like studying a diuretic and measuring urine output.

The results were no surprise: the patiromer group had lower levels of potassium. The curious thing was that the reduction was tiny—only 0.1 mmol/L. If you aren’t a medical person, you will have to trust me that while this was deemed statistically significant, it was clinically meaningless. (The difference in these two is a topic for future columns.)

When the trial was presented this Spring, a health news site had this headline:

Here was the authors’ conclusion.

Notice that they did not mention the primary endpoint.

Their conclusion centered on a secondary endpoint. Language that distracts from the primary endpoint is called spin, and it’s also a topic for another post.

I don’t want to imply anything nefarious in these decisions. The pandemic was a hard time to run a trial.

The point is that a reader of the medical literature now sees a “positive” trial in a major heart journal. One with positive news coverage.

There will be lectures at medical meetings; review articles in journals. A buzz created. There’s a chance a therapeutic fashion will take hold.

Yet no one will know if a $12,000-per-year drug improves outcomes—because the endpoint was changed to something meaningless.

Endpoints. Always look at endpoints. Don’t rely on news coverage or the authors’ conclusions.

PS: We welcome guest columns. If you can highlight an important concept from a recent study in under 750 words, send it in for consideration.

We also welcome rebuttals of our take in the comments. Sensible Medicine aims to be a place where it is safe to disagree because there is much learning that happens during civil debate.

Kinda like looking at neutralizing antibodies, however transient, rather than severe illness, hospitalizations and death in covid vaccine studies

Excellent article on "endpoint shenanigans". Thanks. I would like to see your thoughts on another matter that seems related and bothers me a lot: What is with this new-fangled gimmick of measuring so-called Composite Outcomes in clinical trials? Hypothetical Example: In a randomized, blinded trial, new drug X is put up against old drug Y and the Composite Outcome called (Death or Perianal Itching or Vision Problems) is measured for every person in each arm during a two-month followup interval. Shazam !! Patients who received X "had better composite outcomes" than patients who took Y. How in the hell can a doctor decide rationally from this kind of report whether a patient sitting in her office right now has a reasonable probability of gaining benefit if drug X is prescribed instead of drug Y ? Something about these kinds of "studies" smells fishy to me. The first thing I not infrequently notice is that any one of the three clinical outcome components in this kind of caper will have NOT shown a significant difference in compared groups. But .. .. .. .. .. I did not get an Ivy League undergrad degree so perhaps I have missed some nuances and subtle point(s). Please help. Thanks.