Tech Bros Require Regular Relooks at the Seminal Evidence in Coronary Artery Disease

Let's Revisit the COURAGE trial--and its cousins. Together, they tell a story that approaches fact.

Not every week, but most weeks I read social media posts about getting your heart checked. It could be lifesaving. The pleas often start with a coronary artery calcium scan—which could then lead to a coronary angiogram with possible stent placement.

It’s a compelling story. Heart disease is a leading killer. Sudden cardiac death or massive heart attack can be the first symptom. So if you find a widow-maker-type blockage, you can have it fixed, and disaster is averted.

I call this the clogged pipe paradigm. It dates back to the 1970s. But it is wrong. And worth going over again.

I wrote about it two years ago here on Sensible Medicine. That post had little to no effect, so let’s try again.

The seminal paradigm-busting trial was called COURAGE, published in 2007 in the NEJM.

The background behind COURAGE was that many millions of patients received stents for coronary stenoses. The vast majority of these stents (also known as PCI or percutaneous coronary intervention) were done in the setting of stable disease. Stable disease simply means the procedure was done not during an MI.

The clogged-pipe idea drove the business of PCI. Namely, if not fixed, blockages would lead to MI or death.

Everyone agreed that coronary disease should be treated with optimal medical therapy, such as aspirin and statins and smoking cessation.

COURAGE tested the additive benefit of PCI to optimal medical therapy. Thus, one group got PCI plus OMT, and the other group got OMT only.

Indeed, the name COURAGE fit well, because it was considered courageous to not fix bad blockages.

Inclusion into the trial could occur with a ≥ 70% lesion plus a positive stress test or ≥ 80% lesion without a stress test. Patients with severe CAD, shock, or lesions not amenable to PCI were excluded.

The primary endpoint was a composite of bad things that can happen to patients with CAD. Death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina.

More than 2800 patients were randomized. These were 61-year-old, mostly male (85%) patients. About one-third had single vessel disease, one-third had two-vessel disease and one-third had three vessel disease. One third had disease in the proximal LAD (widow-maker).

Patients in the OMT could cross-over to PCI if they had persistent symptoms on medical therapy. This was planned for and expected in the statistical plan.

Results:

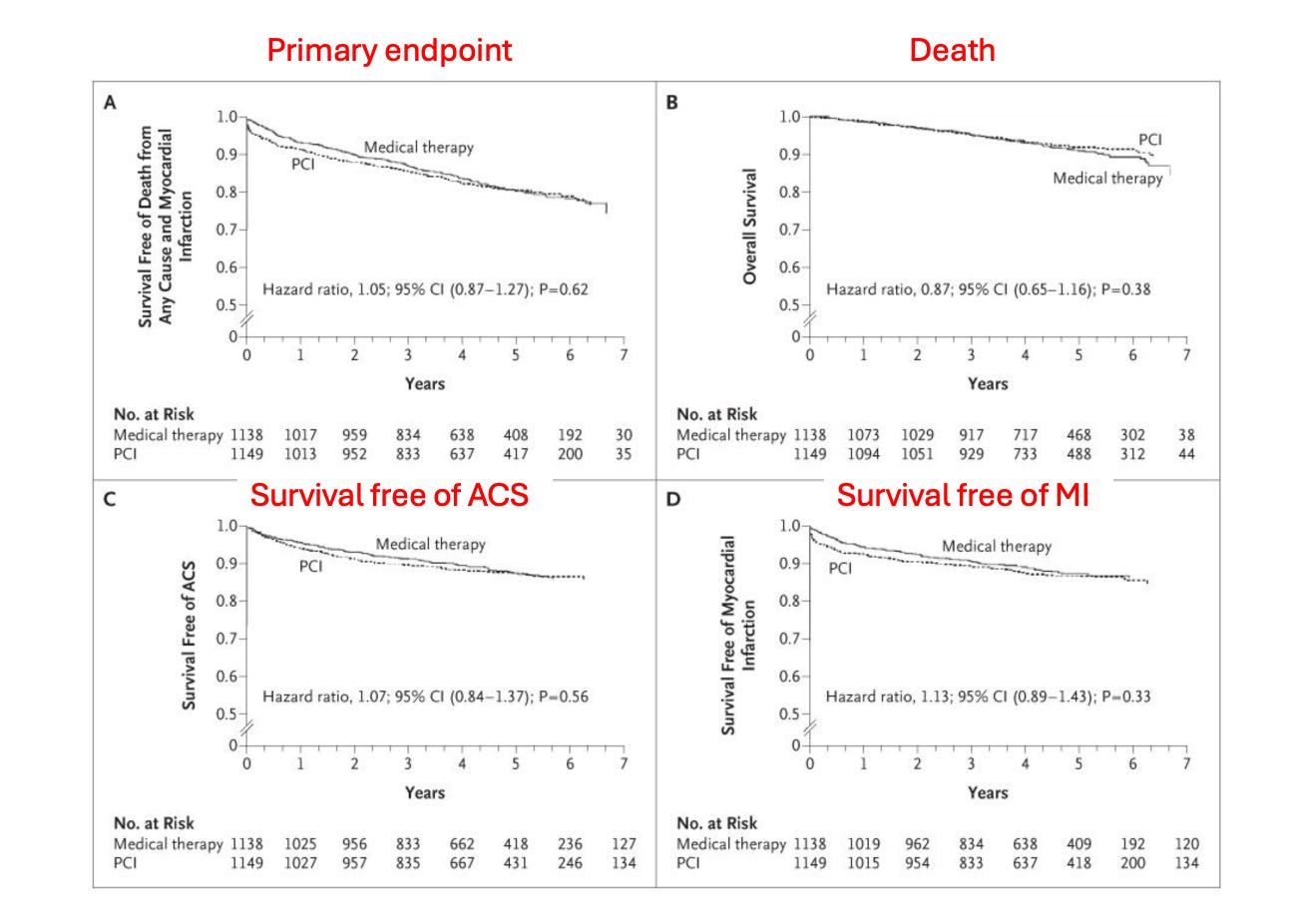

The picture shows the main outcomes. There were no differences in any outcome. None. The primary endpoint had a hazard ratio of 1.05 and 95% confidence intervals going from 0.87 to 1.27.

There were no subgroups identified that showed PCI benefit over OMT.

I present the main trial results. COURAGE investigators have spent years analyzing this trial. And not one subset of patients have been found that did better with additional PCI. They reported 10-year follow-up and still there was no difference in outcomes with PCI.

In my post two years ago, I listed four groups of patients you’d think might garner PCI benefit—those with positive nuclear tests, those with severe disease, those with LV dysfunction and those who crossed over from OMT to PCI. Nope. No difference.

Concordance with Other Studies

COURAGE not only had robust internal validity and adequate power to detect differences, it was also well aligned with other studies of revascularization of stable CAD. Examples include:

Two of the three older coronary artery bypass (CABG) vs medical therapies were also negative.

The BARI-2D trial of patients with diabetes and stable CAD found no benefit to PCI over OMT.

The 5000-patient strong ISCHEMIA trial found no benefit to an invasive strategy with revascularization over a delayed medical treatment first strategy.

And for the win, the REVIVED-BCIS trial took the most severely diseased patients, those with multi-vessel disease and LV dysfunction and randomized them to PCI vs medical therapy. They found zero evidence for benefit in the PCI arm.

Conclusion:

In sum, there is not a shred of evidence that fixing (revascularizing) stable coronary lesions improves outcomes. It just does not.

It is a hard concept because placing a stent to stop a heart attack is one of the most helpful things we do in cardiology. It saves muscle and saves lives.

But stable CAD is different. In stable disease, the focal stenosis is just one symptom or sign of widespread blood vessel disease. And the latter is the target.

The way you target widespread blood vessel disease is with lifestyle and possible meds. You eat well, exercise regularly, avoid smoking, and potentially take statin drugs or BP-lowering drugs. If you have diabetes, you work even harder on diet and exercise.

Then, most crucially, you don’t ignore symptoms of chest pain or shortness of breath.

The reason I am so publicly against screening for CAD is that you don’t need to know your anatomy to target blood vessel disease. Because heart healthy living can simply be a norm.

Knowing your anatomy could easily lead to receiving an unnecessary non-beneficial stent. Knowing your anatomy could lead to unnecessary fear.

I hope this column explains my recent posts on X:

Bonus Content for Paid Subscribers — Many of you may wonder why stenting does not reduce future MI or death.