The American Academy of Pediatrics is Pushing Drugs & Surgery for Obesity

Is it a wise choice? Dave Allely investigates

We are lucky to have this comprehensive essay by medical student Dave Allely on the AAPs’ recent recommendation to push drugs and surgery in children for obesity. I think he summarizes the evidence well, and his conclusions are balanced.

When reading the recommendations, I only had 1 thought. If you put a 12 year old on GLP-1 agonist, what is your endgame? What happens when they turn 22? 32? Do they take it for decades? If they stop and gain weight, they may restart. While the safety profile of these drugs is well known, it is not well known what happens after two decades of use.

Second, I once again wonder why the AAP is not calling for better studies. It might be reasonable to attempt this strategy, but shouldn’t we gather more evidence concurrently? Perhaps the entire recommendation should be a large randomized trial following kids for years and measuring aggregate health outcomes.

I continue to believe the AAPs original sin is that they like to make recommendations, but are less interested in having those recommendations be supported by evidence. Toss in naked partisan politics (they are far left), and you have a recipe for disaster.

Vinay Prasad MD

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently released its first Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) on the evaluation and treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity. The output of this guideline includes Key Action Statements (KAS) and Consensus Recommendations. While much of the content is non-controversial, the use of medications and surgery in this population has some people on edge. First, I would like to mention the relevant KAS and consensus recommendations.

Key Action Statements

“Pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer adolescents 12 y and older with obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile) wt loss pharmacotherapy, according to medication indications, risks, and benefits, as an adjunct to health behavior and lifestyle treatment.”

Grade B recommendation

“Pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer referral for adolescents 13 y and older with severe obesity (BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex) for evaluation for metabolic and bariatric surgery to local or regional comprehensive multidisciplinary pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery centers.”

Grade C recommendation

Consensus Recommendations: “The CPG authors recommend that pediatricians and other pediatric health care providers…”

“May offer children ages 8 through 11 y of age with obesity wt loss pharmacotherapy, according to medication indications, risks, and benefits, as an adjunct to health behavior and lifestyle treatment.”

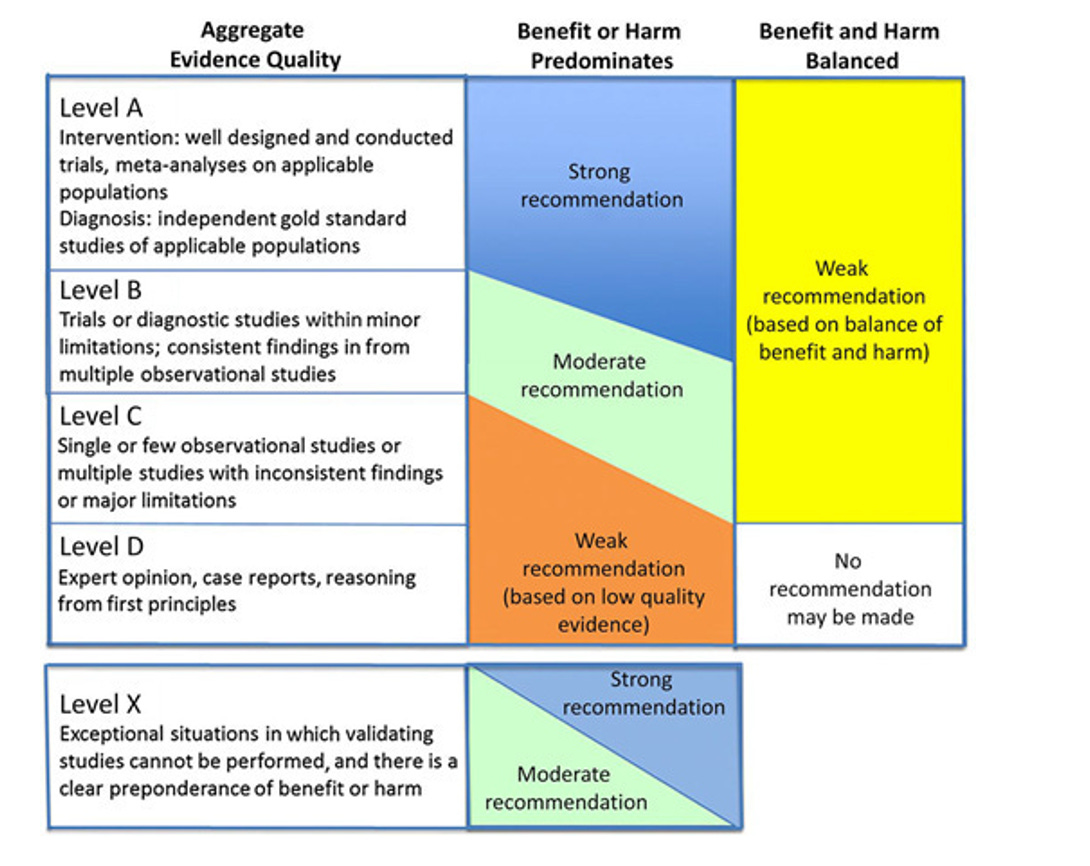

What I think will be useful is to briefly look at the evidence-base for these recommendations before discussing implications. As listed above, the recommendation to offer pharmacotherapy to patients 12+ with obesity was a Grade B recommendation, whereas the surgical referral for patients 13+ with severe obesity was Grade C. Here is the framework used for grading:

Quality of Evidence

“Possible grades of recommendations range from “A” to “D,” with “A” being the highest:

Grade A: consistent level A studies;

Grade B: consistent level B or extrapolations from level A studies;

Grade C: level C studies or extrapolations from level B or level C studies;

Grade D: level D evidence or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level; and

Level X: not an explicit level of evidence as outlined by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. This level is reserved for interventions that are unethical or impossible to test in a controlled or scientific fashion and for which the preponderance of benefit or harm is overwhelming, precluding rigorous investigation.

When it was not possible to identify sufficient evidence, recommendations are based on the consensus opinion of the Subcommittee members.”

Below is a basic summary of the studies they included to make these recommendations. I will pull from one of the technical reports provided.

Weight loss pharmacotherapy for patients 12+ with obesity.

Randomized:

They included 27 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmaceutical interventions, which primarily used Metformin. 74% of the studies showed some positive effect on BMI or BMI SDS. BMI SDS is just another way to measure the change in BMI over time, often used in children as they are growing.

Of note: “…in nearly half of studies, participants and personnel were not blinded.” All but one of the trials included reported the number of participants, per the technical report. 1,646 children in total were included in those 26 studies. Only five of the studies included results beyond six months. And finally, “Magnitudes of BMI reduction were generally similar to those of lifestyle interventions.”

Observational:

Here they include 8 studies, half of which showed benefit from medication. 835 children were included in total for these studies. Four compared Metformin to lifestyle, two of which showed a benefit on BMI.

Surgical Referral for patients 13+ with severe obesity.

11 trials were included, most of which were observational in nature. Seven of these compared surgical intervention to lifestyle or controls. As one would expect, all of the studies comparing surgery to lifestyle showed a significant reduction in BMI, consistently around 15 BMI units, or ~30% reduction in BMI.

What to Make of these Recommendations

There are two main things I’d like to address here. The first is a general impression of the basic recommendations and the desire to address the obesity epidemic we face. The second is what the implications of recommending “weight loss pharmacotherapy” are and what drugs pediatricians might reach for.

Obesity Epidemic

We have an unhealthy population in this country, increasingly so every year. Childhood obesity represents a major medical crisis and is an indictment of the general health of the US. Obviously, the combination of a sedentary lifestyle and over-nutrition lay at the heart of this phenomenon. Medical professionals encourage things like regular exercise, reasonable caloric restriction, and avoidance of especially egregious diets.

In the context of increasing childhood obesity and failure of our lifestyle advice to control the trend, it is only natural that escalating interventions may be tempting. As with everything in medicine, these decisions must be personalized. Intensive lifestyle intervention is difficult to imagine scaling to the number of patients that stand to benefit, to say nothing of the cost.

A 16-year-old with type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and a BMI of 40 should almost certainly be on an aggressive pharmacologic regimen in addition to lifestyle intervention. I’m even open to being convinced that if those measures fail, surgical intervention could be in the best interest of this hypothetical patient. A 13-year-old with a BMI of 30 and no comorbidity is a very different story.

I think some imagine that every obese child or adolescent will suddenly be placed on medications, which seems unfounded. I imagine pediatricians will largely reserve medications for patients with severe obesity, some comorbidity, and a failure of lifestyle guidance and/or behavioral intervention. The data supporting the use of medications and surgery in this CPG is not very strong, largely based on small studies with limited generalizability and/or weak effect size.

Metformin is also a very different drug than Orlistat, the latter being far more concerning in my mind for use in these populations (more on drug choice next). Large RCTs should be funded by the NIH or some other non-industry group to better understand the risks and long-term outcomes for drugs with less data like GLP-1 agonists. Confidence in surgical intervention will also require more RCTs and follow up data over decades, but these procedures will not suddenly be taken lightly due to a Grade C recommendation for referral.

At the heart of this issue is also the knowledge that some of this feels like a band-aid on a hemorrhage. We need to seriously address the twin crises of over-nutrition and sedentary lifestyle. This is largely beyond the patient-doctor relationship and not something physicians are able to control.

Which Drugs are we Using?

Herein lies my biggest qualm with these recommendations. Both the KAS for patients 12+ and the consensus recommendation that includes patients ages 8-11 specifically recommend weight loss pharmacotherapy. A lot of medicine is memorizing associations. We drill these constantly in med school in order to link symptoms -diagnoses-treatment. When I hear “weight loss” I think “GLP-1 agonist”. Click, whirr. Importantly, I do not think Metformin.

Metformin is FDA approved for use in children 10+ for the treatment of T2DM, and it is used off-label for weight loss, but these effects are modest. The FDA has approved four medications for weight loss in children: Liraglutide, Orlistat, Phentermine-Topiramate, and most recently, Semaglutide. Two of these four, Liraglutide and Semaglutide, are GLP1 agonists.

Metformin was the drug used in 19 of the 27 RCTs included in this CPG that led to them recommending pharmacotherapy. Metformin was used in 7 of the 8 observational studies included that led to this recommendation. Just two out of 27 RCTs included used Orlistat, two others used Exenatide (a GLP1 agonist that is approved for T2DM (not weight loss) in children 10+). So only two out of 35 total trials included tested the use of GLP1 agonists, in a grand total of 33 patients, yet I anticipate their use will be increased because of this recommendation.

Though the mechanism of action is shared, it is worth noting that the CPG did not rely on a single study using a GLP1 agonist currently approved for weight loss in these populations. Semaglutide was approved at the end of 2022, and Liraglutide was approved at the end of 2020, so I don’t mean to say that it is reasonable, given the timeframe, to have many trials included using these agents. I simply find it disconcerting that recommendations that may lead to a substantial increase in prescriptions of these two drugs will not have incorporated a single study in which they were tested.

Liraglutide- GLP1 Agonist, Approved in December 2020

A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide for Adolescents with Obesity

299 participants screened, 125 assigned Liraglutide, 126 assigned placebo

12 week run-in period, 56 weeks of treatment, 26 weeks of follow-up without treatment

Results: This is a great figure that summarizes the results

Safety: GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) were more common in the Liraglutide (64.8%) group than placebo (36.5%). 13 participants in the Liraglutide group had adverse events that led to discontinuation, 10 of which were due to gastrointestinal events. Zero patients receiving placebo experienced adverse events leading to discontinuation.

Semaglutide- GLP1 Agonist, Approved in December 2022

Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adolescents with Obesity

229 participants screened, 201 underwent randomization. 134 were assigned semaglutide, 67 were assigned placebo

12 week run-in, 68 weeks of treatment and a 7 week follow-up period

Of note: “Baseline characteristics were similar in the two trial groups, except for body weight, BMI, and waist circumference, which were slightly greater in the semaglutide group than in the placebo group” That’s an important difference if it is what you are basing the results on. The difference isn’t huge but patients with more weight to lose clearly stand to have exaggerated weight loss relative to the other group.

Results:

Safety: There were similar general GI side effects in this study (eg, increased nausea, vomiting) with Semaglutide vs. placebo. Five participants receiving Semaglutide had acute gallbladder disease, all of which had cholelithiasis, one with concurrent cholecystitis. No participants receiving placebo had cholelithiasis. Amylase and lipase levels increased in the Semaglutide group from baseline to week 68, with no cases of pancreatitis reported.

Final Thoughts: GLP1 agonists are good at reducing BMI, and have some significant side effects, requiring frequent monitoring. Here in the US, drug developers design and run the trials that are used to determine approval of their products. They are smart, and we can see that trial design can have a profound impact on interpretation of results. The 26 weeks of follow-up without treatment in the Liraglutide study showed that patients return to baseline BMI within ~6 months of discontinuing treatment.

The Semaglutide trial used just 7 weeks of follow-up, and though we can see the BMI rapidly rising in that brief period (top-left graph of the above results), it looks much cleaner overall. Of the six figures in those results, only one displays data from the follow-up period. So, we are left with drugs that are highly effective if you keep taking them, with non-trivial side effects even in optimized conditions (eg, trial participants using run-in period, frequent monitoring).

I am quite confident that GLP1 agonists function to reduce BMI in adolescents. I have reservations about tolerability, adverse effects (eg, cholelithiasis), and long-term use in these patients, especially with respect to GI function, lean muscle mass, etc. The AAP’s recommendation will likely lead to increased prescriptions of Liraglutide and Semaglutide, though neither were included in the evidence base.

Other FDA-approved Meds for Weight Loss: I focused mostly on the GLP-1 agonists, but here is a breakdown of the trials that led to approval of Orlistat and Phentermine-Topiramate. Both are FDA approved for ages 12+. Of note: neither of these trials had follow-up periods off medication included in the results.

Orlistat- A lipase inhibitor

Effect of Orlistat on Weight and Body Composition in Obese Adolescents

539 participants randomized to orlistat or placebo in 2:1 fashion. 357 orlistat, 182 placebo.

54 week study with a two week placebo run in prior to randomization

Both groups placed on hypocaloric diet, targeting 40% reduction in caloric intake

Results: Both groups had lowered BMI in the first 12 weeks after randomization. The BMI stabilized for the orlistat group but increased to beyond baseline for the placebo group.

BMI reductions by trial arm:

5% or higher decrease in BMI: 15.7% of placebo and 26.5% of orlistat.

10% or higher decrease in BMI: 4.5% of placebo, 13.3% of orlistat.

Safety Results: 12 orlistat and 3 placebo participants discontinued treatment because of adverse events. A 15-year-old girl receiving orlistat had symptomatic cholelithiasis that led to cholecystectomy. One placebo and ten orlistat recipients developed ECG abnormalities, which were not believed to be related to medication upon review by an independent cardiologist. (Not entirely reassuring given 10:1)

At the end of the study, 6 participants in the orlistat group were found to have asymptomatic gallstones not seen at baseline, versus one in the placebo group. Ultrasound also identified 2 additional new renal abnormalities in the orlistat group.

Phentermine/Topiramate- FDA approved in 2022 for weight loss in kids 12+

Phentermine- Sympathomimetic, weight loss may be due to increased release of norepinephrine from the hypothalamus

Topiramate- Anti-epileptic with established effect of weight loss. The mechanism of action behind this effect is not established.

Phentermine/Topiramate for the Treatment of Adolescent Obesity

56-week trial, randomized 1:1:2 to receive placebo, mid-dose PHEN/TPM or top-dose PHEN/TPM

All participants were instructed to follow a mild hypo caloric diet (500kcal/day deficit) and given lifestyle training

325 participants were screened, 227 were randomly assigned. 56 placebo, 54 mid-dose, 113 top-dose

Study completion rate was 56.9%, 75.5%, and 65.2%, respectively, for placebo/mid-dose/top-dose

Of note: Weight, BMI, and waist circumference were all highest in the top-dose group at baseline (see Table 1) *This is another detail that I think is worth noting. The top dose group average weight was 6.3kg (13.86lbs) higher than placebo— they have more weight to lose. BMI was 2.6 units higher on average and waist circumference 5.4cm higher on average for top-dose versus placebo.

Results: Mean change from baseline at week 56

Results will be reported as Placebo—Mid-Dose—Top-Dose

BMI: (+1.2)—(-2.53)—(-4.15)

Weight(kg): (+6.57)—(-5.49)—(-9.23)

Waist Circumference(cm): (+0.31)—(-7.42)—(-9.27)

*Note: When your outcome measure is mean change from baseline and the group receiving top-dose had higher BMI/Weight/Waist circumference at baseline, your results are partially mediated by that difference

Safety: Three serious adverse events occurred in two patients in the top-dose group. One participant was hospitalized for a bile duct stone within one week of completing the study. The other experienced depression and suicidal ideation, though it was at the mid-dose, prior to titrating up. This was originally considered related to the study drug and it was discontinued, though there were several recurrences over the following 105 days.

*Note: The only reason I included the single patient with depression/SI in this overview is that overall, “Events related to psychiatric disorders (system organ class) occurred in four participants (7.4%) in the mid-dose group and 10 participants (8.8%) in the top-dose group compared with one participant (1.8%) in the placebo group.”

The AAP is the most dangerous "professional" association in the country. Their response on COVID has been beyond the pall. Their comments on gender issues are right there with the COVID advice. And this is just more of the same.

If I were a pediatrician, I would be forming a new professional society just so that I would not have to hide under my bed in shame from these pronouncements. The lack of pushback from this entire specialty is mind numbing. I pity our poor children.

We have such a great therapy for childhood obesity already. GYAOaP qd. That's the brand name. I believe the generic name is Get Your Ass Outside and Play.