The AQUATIC trial of oral anticoagulation plus aspirin is this year's most important trial

For years and decades, doctors thought that patients with CAD and AF required both aspirin and anticoagulants. Gosh were we wrong.

The AQUATIC trial, conducted in France, studied low-dose aspirin (ASA) added to oral anticoagulation (OAC) in patients with an anticoagulation indication [mostly atrial fibrillation (AF)] and chronic coronary artery disease.

This combination is super common. It happens in two ways: one is that a patient has been on ASA for years, and develops AF, and the doctor starts OAC without stopping the ASA. The other way is that a patient with AF gets diagnosed with CAD by some means and then the doctor adds ASA.

The idea is that ASA covers the coronary artery disease and the OAC covers the AF. A few smaller studies had suggested harm using the combination, but these had little effect on the common practice of using both agents.

The Trial

The French team randomized 872 patients to two arms: one with OAC plus ASA tablet or OAC plus a placebo tablet.

Patients had to have serious CAD, including a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) more than 6 months before enrollment. So these were not soft ASA indications.

Patients were 72 years old, 85% male and three-fourths had had a previous MI. The mean CHADSVASC score was 4. OAC could be with any of the direct acting drugs or warfarin.

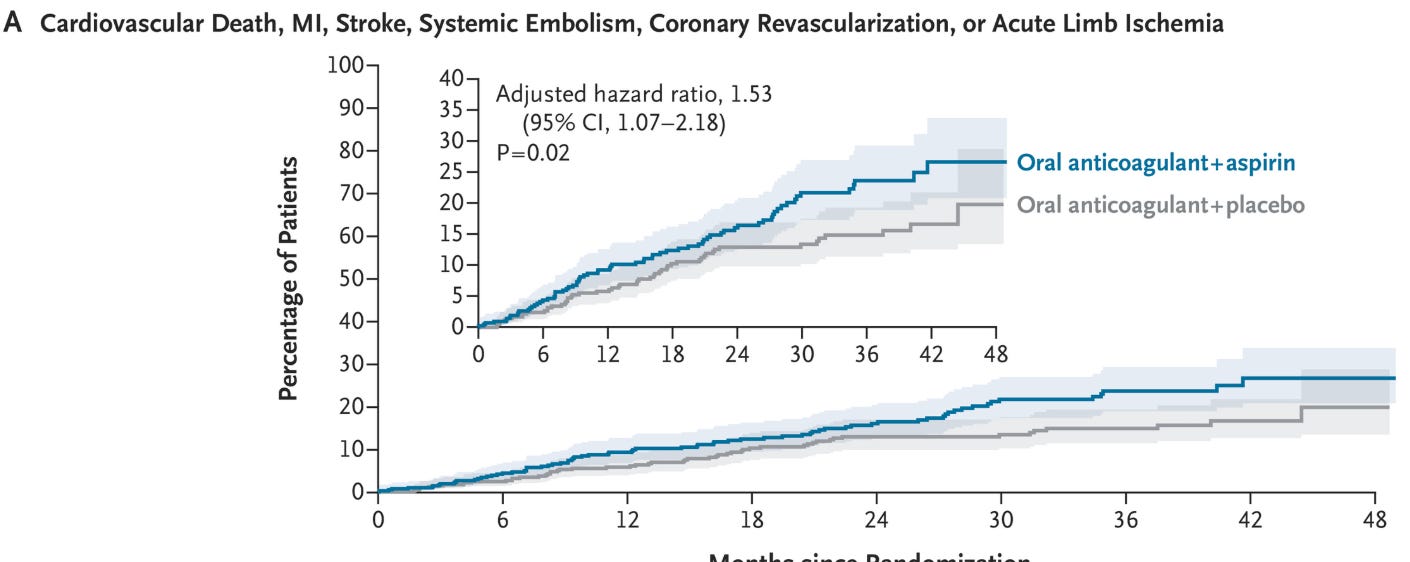

There were two endpoints: an efficacy endpoint looking at thrombotic (clot) events—CV death, MI, stroke, systemic embolism, coronary revascularization or acute limb ischemia. The key safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Before I tell you the results, let’s pause and think about what we expect. We’d expect the addition of asa to reduce thrombotic events, but we would worry that it would increase bleeding. So then we’d have to balance reduction of events and increase in bleeding to sort out a net effect.

THIS IS NOT WHAT HAPPENED.

The trial had to be stopped prematurely because an interim analysis showed harm from the combination arm.

Here is a picture of the efficacy events:

The combination arm had a 53% higher rate of a primary efficacy endpoint. The 95% confidence intervals went from 1.07-2.18. And the P value was significant at 0.02.

Worse was the bleeding outcome: The rate of major bleeding was 10.2% vs 3.4%, respectively (HR = 3.3; 95% CI, 1.9-6.0).

The authors concluded that combination therapy was clearly worse than single OAC.

Four Important Lessons:

First is that there is little uncertainty here. The absolute difference in the primary outcome (16.9% vs 12.1%) is 4.8%, which translates to a number needed to harm of only 21. The bleeding risk is really striking. Here the absolute risk increase was 6.8% (10.2% vs 3.4%); number needed to harm of just 15.

Second, AQUATIC results comport well with two previous trials (AFIRE and EPIC CAD) which also found worse outcomes with dual pathway combined therapy. When similar trials find similar things, we become more confident in the results. I do wonder why the combination increased thrombotic events in AQUATIC. The previous trials found a wash for ischemic events and more bleeding in the combination arm.

Third, the AQUATIC authors have shown that important medical questions can be answered with proper trials. Too often, clinical trials are designed to find a positive result for a profitable new therapy. In the first part of my talk on critical appraisal, I teach learners to ask what a trial is for. Is it for answering an important question or is it for marketing? AQUATIC was clearly done to answer a common question in clinical medicine. Good on the authors.

The last message is that the failure of a combination approach shows that the human body is unlike a machine where you can independently tweak systems. Aspirin is indicated in patients with chronic coronary disease. But when this patient also has a reason to take oral anticoagulants, the combination of the two drug classes is not simply the sum of two beneficial therapies.

Our coagulation system is a delicate balance between thrombosis (clotting) and bleeding. Blocking both platelets and coagulation should have always required separate testing.

I wrote on Medscape that AQUATIC shines not only because it informs a common scenario but also because it infuses us with humility regarding the translation of evidence.

For years and decades, we assumed that the patient with both CAD and AF required two separate agents. That thinking made sense; it was plausible, but it was wrong.

And it was trials that provided the answer. The final lesson is, once again, when in doubt, randomize.

P.S. Few trials have been this relevant to my practice. I estimate that it is at least once weekly I am stopping ASA in an AQUATIC like patient.

In Sweden (most if not all of us) we stop ASA as soon as anticoagulants are indicated, so it’s assuring to have evidence from a RCT

As a gastroenterologist in clinical practice for over 30 years, I’ve been summoned to the emergency department and ICU countless nights for patients bleeding on dual anti-thrombotic (DAT) therapy, typically ASA in combination with warfarin or another anticoagulant. I’ve been de-escalating those patients and almost every other patient on DAT I encounter to a single anti-thrombotic, citing the known increased risk of hemorrhage from DAT and the conspicuous lack of demonstrated benefit for most patients. The AQUATIC trial has provided strong evidence this is the right thing to do; thank you for covering it here.