The Evidence that Established Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery is Worth Studying

The study of the week goes back in history to look at the surgery vs medicine trials in patients with severe coronary heart disease. Wow.

(Editor’s note. I had accidentally limited comments to paid subscribers. Comments are now open to all.)

Two quick stories as background.

I remember caring for an older man who presented with a minor heart attack. We got him squared away easily. I was then struck by his history because more than a decade before this presentation, doctors had discovered severe multi-vessel coronary disease and they had recommended bypass surgery. They told him he would die without it. He refused. And he didn’t die. He lived another decade with little trouble—on a few tablets.

Second story: When I trained in cardiology, I recall being upset that veterans with severe coronary artery disease had to wait weeks to have their coronary bypass surgery (CABG). My angst was for naught. Had I looked back at the seminal trials, I would not have worried. In fact, the seminal trials of CABG vs medical therapy are quite surprising.

In this week’s study of the week, let’s look back at those seminal trials. Buckle up.

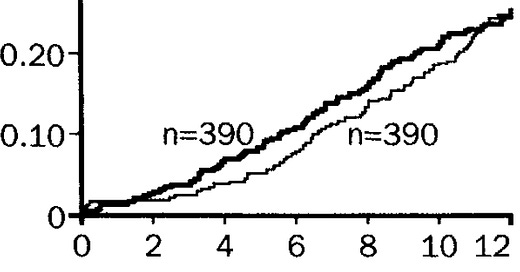

The Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) trial came first. It started in 1975 and was published in 1983. Patients with amenable coronary disease were randomized to either bypass surgery (n =390) or medical therapy (n=390). The primary endpoint was death. The survival curve showing no difference over 12 years is below.

A year later, the NEJM published the VA Cooperative trial. The trial procedures were similar. CABG vs meds in nearly 700 patients. The eleven-year rates of survival were 57 vs 58% respectively. The survival curves graphically show the lack of CABG benefit over meds.

The European Coronary Surgery Study reported four later in 1988. Once again, CABG was compared to meds in 767 men. “Twelve years after assignment to treatment, there were 201 deaths — 109 in the medically treated group and 92 in the surgically treated group.”

The survival curves below show a definite benefit for surgery at 5 years, but over the next five years, the curves come together. In the end, that difference in 17 deaths barely reached statistical significance at a P-value of 0.043.

I know what you may be thinking. Mandrola, you are off your rocker. These are old trials. Modern trials must have been better. Modern heart surgery uses the left internal mammary artery whereas older surgery used mostly vein grafts.

Ok. Let me show you a big modern trial.

The STICH trial, published in 2011, randomized about 1200 patients with impaired LV systolic function and severe coronary artery disease amenable to surgery to CABG or medicine alone. The primary outcome was death.

Death occurred in 41% of patients (244) in the medical arm vs 36% (218) in the surgical arm. The edge to surgery did not reach statistical significance. This, despite the fact that patients had severe multi-vessel disease and bad ventricular function. About 70% of these patients had proximal LAD disease—the widow-maker.

The STICH trialists amended their study protocol and followed these patients for 10 years. They called the extension study STITCHES.

The survival curves are similar, but since more patients died, (or had outcome events in statistical parlance), the small advantage in death now reached statistical significance. It should be noted, however, that after a decade, in a trial of 1200 patients, the difference in deaths was only 39.

You might wonder how bypass surgery became established as a common everyday procedure despite all these non-significant trials. Recall also that this was an era where medical therapy included only nitrates and aspirin.

I look forward to any comments from surgeons, but I see three main reasons.

One was that subgroups within these non-significant trials did better with surgery. Yet we all know the limits of subgroups, especially when taken from trials with non-significant primary endpoints.

Another reason was crossovers. Each of these trials were labeled CABG vs Meds. But many patients in the medical arm eventually crossed over to surgery. The intention-to-treat principle holds that cross-over patients are analyzed in the medical arm. That surely reduces any surgical advantage. Another way to consider these trials would be immediate vs delayed surgery.

The other savior for bypass surgery came from a Canadian research team from McMasters University. Professor Salim Yusef organized a study wherein he and colleagues got the authors of these studies to share individual patient level data for a meta-analysis.

It’s now known simply as the “Yusef meta-analysis.” Lancet published the study and here is the main survival curve:

When you combined the studies, about 1300 patients were randomized in each group. The CABG group had a significantly lower mortality than the medical treatment group: at 5 years (10.2 vs 15.8%; odds ratio 0.61 [95% Cl 0.48-0.77], p = 0001), at 7 years (15.8 vs 21.7%; 0.68 [0.56-0.83], p<0.001), and 10 years (26.4 vs 30.5%; OR 0.83 [0.70-0.98] p =0.03.

Yusef and colleagues also noted the subgroup findings. The risk reduction with surgery was greater in patients with left main disuse and in those with disease in three vessels.

I was struck by the meta-analysis authors’ contention that each of the trials were underpowered. They recommended larger trials. But that is hard for me understand because each of the CABG vs Medical trials were carried out for decade—and each had many outcome events.

Take-home:

This post is not meant to question the value of coronary bypass surgery. If I had severe angina, heart failure, left main or multi-vessel proximal disease with LV dysfunction, I would strongly consider bypass surgery. If I were unstable and had severe disease, I’d consider CABG.

The main take-home of this post is to emphasize the extreme (near-miraculous) stability of stable coronary disease. Had this fact been better appreciated at the time, I think it would have reduced our enthusiasm for many things we do in cardiology.

The clear stability of stable coronary disease is surely why no trial of stenting or angioplasty of stable disease has ever shown a survival advantage.

This stability of coronary disease is another reason why I am not enthusiastic about early detection of disease with coronary artery scans.

I hope some heart surgeons happen by this column and offer their comments. JMM

In 2014, my EP discovered an aneurysm (4.5 cm) on my ascending aorta. At the same time, I was told my LAD was 99% blocked. I was given the choice of mesh repair of the distended artery, along with a standard bypass procedure on LAD (requiring open heart surgery) -- or watchful waiting. Not wanting a future life of "tiptoeing on eggshells," I opted for the surgery. As an added enticement, I was told that if I chose the open heart procedure, the surgeon (a famed Houston doctor who was a protege of the god-like Michael DeBakey) would also attempt a myectomy to reduce the non-obstructive HCM in my left ventricle. Encouraged by the confident demeanor of the surgeon and his impressive credentials, I agreed to the full-Monty. (I was also told that the doctors would attempt to ablate my A-fib "while they were in there.") The entire procedure took 6 1/2 hours and I spend 2-3 days in IC for recovery (a horrible experience). The bill came to more than half-a-million dollars, which (thank goodness!) Medicare paid. Fast forward to the summer of 2022 when I was experiencing myocarditis-like symptoms after taking the Covid vax (an "impossible" connection my cardiologist stated, given my 70+ age and the "fact" that vax-induced myocarditis only affects young men). Insisting on further examination, my doc complied by ordering arthroscopy which discovered a couple of interesting situations. First, the heart muscle of my apex was found to be necrotic (dead) and therefore not pulsing to improve the volume of blood/circulation from my left ventricle, as the myectomy had intended. Second, the scan showed that the 2014 LAD bypass had completely failed and that the blood flow was traveling through the original LAD (which, incidentally, now showed to be only 70% blocked -- not the 99% that the 2014 diagnosis stated) and was capably carrying the load during my current daily bouts of intense exercise). Finally, I awoke from my $500K+ surgery with a (surprise!) pacemaker, suggesting that perhaps the attempted ablations of my A-fib had been irreparably botched and therefore "covered" by the pacing device. Since my surgery, I began wondering how many other "life-saving" medical procedures have been performed on countless trusting patients solely to enrich the hospital and doctors involved? And if the old saying might actually be true that "doctors bury their mistakes." Over the recent decdes, we've herd about countless cases of needless stenting and bypass procedures performed on innocent patients who haven't been helped one iota by these practices. Furthermore, we've had no convincing scientific data that these procedures are life-saving or even helpful (except in the instances of an actual MI in progress). Performing unnecessary surgical procedures on unsuspecting patients should be a punishable crime -- and the physicians who profit should be treated like the criminals that they are. Indeed, the willful ignorance on the part of the entire practice of cardiology by condoning these practices and not actively seeking scientific proof of their efficacy should be called into public examination. When will there be a reckoning or justice? When will cardiology reform itself? When will individual practitioners "come clean?' Tragically, not in my lifetime, I dare say.

My cardiology fellowship spanned the years 1976-78 when the enthusiasm for coronary bypass was just taking off. We had three teams of thoracic surgeons and the operating rooms were quite busy. I remember there being a lot of drama and the surgeons were often regarded as near gods because they were actually "doing something" about it. Some of the older doctors raised some questions about the utility of the surgery but they were quickly marginalized and regarded as obstructionists and mossbacks. As a young doctor at that time, it was easy to get swept up in the general enthusiasm and none of us wanted to be labeled as medical reactionaries. Toward the end of my fellowship training I had a case that raised a question in my mind about the separate pathologies of stable coronary disease and acute myocardial infarction. I can provide details on that if anyone is interested but, in the interest of brevity will put it into a separate post.

I agree with Dr. Mandrola that none of the differences in the studies cited are significant. But those numbers are virtually identical to those used to justify long term treatment with statin drugs for patients said to be at risk for coronary artery disease. Why the difference in these assessments of these numbers?