The Meaning of "Guideline Directed"

The Study of the Week explores one of the most important meta-analyses in cardiology today

We can all agree that evidence from clinical trials should guide practice. But. But. There are snags.

One problem with evidence-based practice is that it’s harder than many experts would admit. Today I will use an example in the heart failure space.

Many heart failure experts vigorously advocate for rapid and complete use of the four classes of drugs that have yielded positive results in trials.

This aggressive advocacy has led professional organizations and hospitals to create incentives to use these drugs. Sticks more than carrots.

If an electronic record in a hospitalized patient sees anywhere the words “heart failure” the doctor is sent big red boxes to fill out about the prescription of these “evidence-based medicines.”

These bright red prompts are to minimize penalties the hospital might receive if they are practicing low quality care.

I will show you a super-important study published nearly a decade ago that highlights the problem with robotic application of “quality” care.

Dr Dipak Kotecha and colleagues in the UK decided to look at one common condition that may modify the benefit of a drug class in heart failure. The drug class is beta-blockers. The condition atrial fibrillation.

It’s an important topic because the two (common) conditions share both association and causation. Namely, AF can associate with heart failure and AF can cause heart failure. The reverse is likely true as well. Heart failure can cause AF.

Another piece of background: beta-blockers have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with heart failure due to weak pump. We now call this HFrEF or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The majority of patients enrolled in beta-blocker trials were in regular sinus rhythm.

The authors searched the literature for large low-bias trials of beta-blockers in patients with heart failure due to low ejection fraction. They found 11 trials. They were able to obtain the individual level patient data.

This meta-analysis included more than 18,000 patients. Most (76%) had sinus rhythm at baseline. About 17% had AF at baseline, and the others had a smattering of other rhythms, such as pacing.

They then analyzed the two groups—SR vs AF—for a primary endpoint of total mortality. The graph shows the clear results:

For patients with SR at baseline, beta-blocker use reduced the risk of death by a whopping 27%. The hazard ratio was 0.73, with tight 95% confidence intervals ranging from 0.67-0.80. You can also see steady separation of the curves. That is, the longer the therapy, the more the benefit.

But. But.

For patients in AF, use of beta-blocker had no effect. The curves are nearly identical.

The authors saw the same pattern in admissions to the hospital for cardiac reasons. Benefit when in SR. No benefit from beta-blockers in AF.

The authors also took the AF group and did subgroup analyses looking for signals based on age, sex, EF, heart rate, use of other meds, such as digoxin. They found no subgroup of patients with AF at baseline that benefited from beta-blocker.

Comments and Take Homes

One criticism I hope you are thinking of is the matter of subgroups and power. Trials are powered to detect differences in the entire population. Here we compare a group of patients in SR (N ≈ 14,000) to much smaller group in AF (N ≈ 3000). Perhaps, you wonder, maybe there weren’t enough events in the smaller group to detect a difference?

Well, the authors write that in the AF group, they had more than 633 deaths=-enough to detect a signal if there was one.

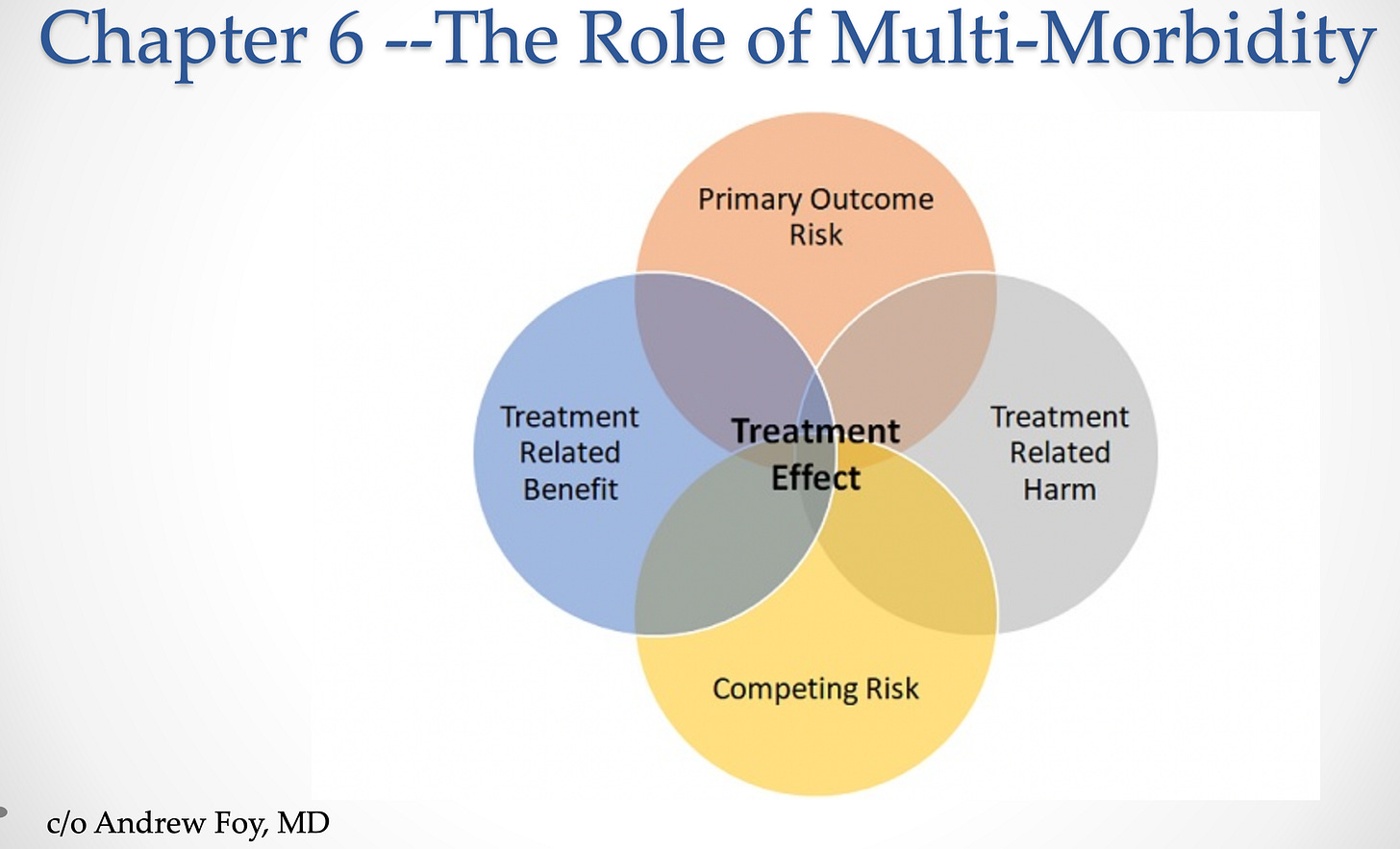

The next question you might have is plausibility. I would offer a few reasons this is plausible. One is that AF increases the risk of heart failure. Anytime you deal with higher risk, the equation between primary-outcome risk vs competing risk changes. The other change at higher risk is the balance between treatment benefit and treatment harm. See the figure from Andrew Foy.

Another reason for the differing effects of beta-blockers is heart rate. Slowing the rate in AF may not confer the same benefits that it does in SR. There are also structural and cellular consequences of AF that may alter the effect of blocker.

The authors nicely summarize the major lesson from this paper.

The results of our analysis suggest that the substantial benefit identified in patients with sinus rhythm should not be extrapolated to patients with atrial fibrillation.

I highlight this paper because the nuance of applying evidence from trials to patients in real life is widely under-rated.

While this paper does not argue that beta-blockers cause harm in patients with AF and heart failure, it strongly suggests that algorithms promoting beta-blocker use in all patients labeled with a diagnosis of heart failure are fatally flawed.

This means that when patients present with heart failure and AF, clinicians should be free to use drugs that they see fit. This may or may not include beta-blocker. We should not receive a penalty for deviating from evidence-based practice.

I advocate for the use of evidence in the strongest terms. But this does not equate to blindly following overly simplistic algorithms, especially when tied to financial incentives. These are a blight on the evidence-based practice movement.

As always, we welcome your comments. Thanks for your support. Sensible Medicine is a user-supported site. It remains free of advertising. JMM

Excellent post, John. Your last paragraph reminds me of a short letter to the editor of the BMJ written by Dr. David Sackett who is considered the “father of evidence based medicine”. The 1996 letter was in response to criticism of EBM and is titled “Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t”. It is a short one page letter and worth reading from time to time. One notable quote, of which there are many, from the article: “Any external guideline must be integrated with individual clinical expertise in deciding whether and how it matches the patient’s clinical state, predicament, and preferences, and thus whether it should be applied. Clinicians who fear top down cookbooks will find the advocates of evidence based medicine joining them at the barricades.” Dr Sackett’s concerns in the letter were prescient as to how EBM has been hijacked by financial managers, political activists, and Big Pharma.

I’m not sure that evidence-based medicine makes any sense, John.

The problem is, that it requires explanatory theories first, and that is often ignored. Studies are done that get financed by Big Pharma largely. There are some that are done without that funding, and there are some older studies that were done before the massive corruption.

But for example, for heart failure, I am convinced that small amounts of T3 can reverse HF. Yet the studies aren’t really done because there is no money in that, and no explanatory theories that are currently in vogue supporting it.

There is certainly evidence for decades that raising T3 is the solution to HF. For instance several studies showed risk of death higher with lower T3.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002934304006576

All-cause mortality was 23% (n = 64) after a mean (±SD) of 12 ± 7 months of follow-up; 47 (73%) of the patients died from cardiac causes. The mean ejection fraction was lower in those patients who died than in those who survived (26% ± 8% vs. 31% ± 8%, P < 0.001), as were levels of total T3 (1.0 ± 0.4 nmol/L vs. 1.3 ± 0.3 nmol/L, P < 0.001) and free T3 (3.2 ± 1.4 pmol/L vs. 3.7 ± 1.0 pmol/L, P < 0.001). In a multivariate model, ejection fraction (odds ratio [OR] = 2.0 per 10% decrease; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.4 to 2.8 per 10% decrease; P < 0.001) and total T3 level (OR = 0.3 per 1-nmol/L increase; 95% CI: 0.1 to 0.5 per 1-nmol/L increase; P < 0.001) were the only independent predictors of all-cause mortality. In an alternative model using free T3 levels, ejection fraction (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4 to 2.7; P < 0.001) and free T3 level (OR = 0.6 per 1 pmol/L; 95% CI: 0.5 to 0.8 per 1 pmol/L; P <0.02) were associated with all-cause mortality. When we considered cardiac mortality alone, male sex (OR = 3.5; 95% CI: 1.7 to 13; P < 0.04), ejection fraction (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.2 to 2.5; P < 0.006), and total T3 level (OR = 0.3; 95% CI: 0.2 to 0.7; P < 0.002) were independent predictors with the multivariate model.

Conclusion

Low T3 levels are an independent predictor of mortality in patients with chronic heart failure, adding prognostic information to conventional clinical and functional cardiac parameters.

——

It’s safe

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002914997009508

And it works

https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/prc/2008/00000003/00000001/art00003

And yet, there are virtually no doctors who pay any attention to this. HF is a result of very low cellular energetics and often accomplices type 2 diabetes and other metabolic issues that come from high fat burning, minimal oxidative phosphorylation, high glycolysis producing lactate, high build up of lactate…

The explanatory theory would suggest, let’s give patients small doses of T3 and get their cellular energetics back up. And it works. But nobody is doing it, nobody talks about it, because the “evidence” isn’t there because Big Pharma doesn’t want the evidence to be there.

That’s the problem with the “evidence based” approach.