The Nutritional Cold War

Part 2: Ultra-Processed Panic: What the Evidence Really Shows

Today, James McCormack is back with part two of his three-part series on ultra-processed food. If you have not read yesterday’s post, please do so before diving into today’s.

Adam Cifu

What Do the UPF Cohort Studies Show About Important Health Outcomes?

The table below presents the results of ten of the principal evaluations conducted in adults over the past five years, examining the amount of UPF consumed and the likelihood of experiencing a poor outcome, such as death, cardiovascular disease, or cancer.

In every observational study, different categories — 10-20%, 30-40%, etc. — of the amount of UPF eaten are compared to the lowest category, which serves as the reference. The % used for the reference/baseline category also varies from study to study. The numbers in the colored cells represent the relative percent differences in the health outcome compared to the reference. The statistically significant differences are highlighted in red. For the other squares, we cannot tell if the difference was real or just a chance finding. And most importantly, even a statistically significant finding does not mean the size of the difference is large enough to be important (or for you to change what you eat - that is for you to decide once you know the absolute numbers).

These studies indicate a consistent association with worsening health outcomes occurs when over 40% of a person’s caloric intake comes from UPF. When the intake is < 30%, there is no convincing observational evidence that UPF has an adverse effect on health outcomes. In the 30-40% range, there is certainly a suggestion there is an association with worse health outcomes, but none of the numbers in the yellow and green boxes were statistically different from the baseline.

That is the main observational evidence we have in adults for UPF. Remember that observational studies, although far from perfect, are typically considered the best available evidence for looking for an association between UPF intake and health outcomes. Globally, for approximately 20% of the countries listed earlier (in the figure in Part I), the average UPF intake exceeds 40%. This is why many people consider UPF intake to be a worldwide health concern. However, for 50% of the countries, the average intake is less than 30%. Context is important.

In other words, when it comes to UPF as a whole, the main thing we can get from these observational studies is that the dose makes the poison, rather than that all UPF is “bad”.

What Do the UPF Sub-Type Cohort Studies Show?

Above 40%, and possibly above 30% UPF intake is associated with negative health outcomes. However, there is nuance to the association between UPF and health. Researchers have explored what the observational evidence shows for the specific subtypes of the NOVA UPF classification. These categories were listed in part 1 and include sugar-sweetened beverages, savory snacks, processed meat, sweet snacks, desserts, etc. You will see why simply saying UPF is “bad” is an oversimplification.

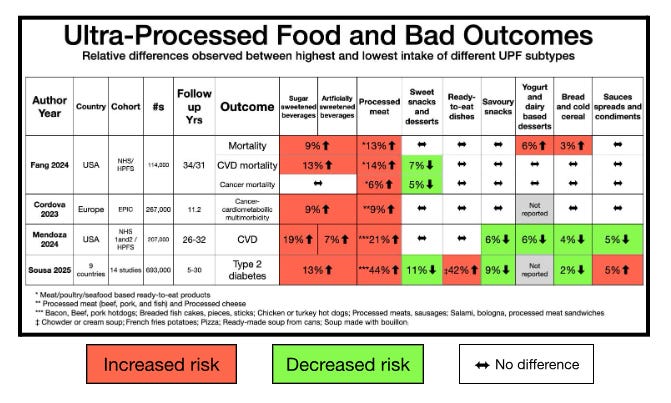

In the figure below, the findings from three observational studies examining the outcomes of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, comparing the highest versus the lowest intake of different UPF subtypes, are provided.

The numbers in the table are all the differences that were statistically significant. Red means an association with a higher risk was observed, green indicates a lower risk, and white means no difference. What is clear is that there are two leading bad actors in the NOVA definition of UPF. These two groups are sugar (or artificially) sweetened beverages and processed meat. All the other UPF categories are pretty much neutral, with some UPF categories even being associated with a lower risk of clinical outcomes. This again gives weight to the argument that thinking about UPFs as a single entity is at best misleading and, when it comes to your nutritional health decisions, wrong.

But What About Type 2 diabetes (T2DM)?

When it comes to T2DM, there is an important nuance regarding the evidence surrounding UPF and T2DM. This is relevant because there is a lot of press about the rise in T2DM, and many people link this rise to the rise in UPF intake. The reason I have separated out T2DM is that, in this matter, T2DM is an intermediate step on the possible way to important clinical outcomes. T2DM is typically diagnosed based on a specific glucose threshold, and is therefore a surrogate marker, rather than a hard clinical outcome, such as heart attacks and strokes. Heart attacks and strokes are associated with higher glucose numbers. I have already provided you with the evidence for the association between UPF and these clinical outcomes, and these studies typically included people with T2DM. Nonetheless, there is evidence of an association between UPF intake and an increase in glucose and therefore, an increase in the number of people getting a diagnosis of T2DM.

In 2025, Souza et al. published a meta-analysis of 14 observational studies examining the relationship between UPF consumption and T2DM diagnosis. When they compared the highest to the lowest UPF consumption, they found that higher consumption (typically >40% versus <20% or 10 servings per day versus 3-4 servings per day) was associated with a 24% higher risk of T2DM. Unfortunately, the authors don’t provide a breakdown of the risks for different UPF bracket amounts (e.g., 20-30%, 30-40%, etc.). However, the largest study included in the Souza meta-analysis did examine different bracket amounts, and there was no associated increase in T2DM until the UPF intake exceeded 40%. In the >40% group, there was a 21% increase in the risk of T2DM. This again shows that when it comes to the association between UPF and a diagnosis of T2DM, the dose makes the poison.

What about Weight and UPFs?

Weight is a very tricky topic, and discussions require context and nuance. Personally, I like Yoni Freedhoff’s idea, “Your BEST WEIGHT is whatever weight you reach when you're living the healthiest life that you actually ENJOY”

That aside, several observational studies have shown that an increase in weight is associated with a higher intake of UPF. This makes sense as UPFs are energy dense; they don’t make you feel as full for as long as other foods. They are also tasty in a way that makes you want to keep eating, even if you're not hungry.

There is evidence to support this reasoning, and it comes from a randomized controlled trial—the highest level of evidence for determining cause and effect. In this trial, 20 adults lived in a research facility for 28 days. During this period, participants spent two weeks on an ultra-processed diet and two weeks on a diet consisting of unprocessed foods. The meals in both arms were matched for calories, macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbs), salt, and fiber — everything except processing. People were allowed to eat as much or as little as they desired. Participants on the UPF diet consumed approximately 500 more calories per day than those on the unprocessed diet. On the UPF diet, people gained about 2 pounds in 2 weeks, while on the unprocessed diet, they lost about 2 pounds.

This likely explains why observational studies examining UPF find an association between UPF intake and weight gain. People simply eat more of it - or in other words, the more calories you eat, the more weight you gain. Again, when it comes to weight, the dose makes the poison.

What Can We Say About UPF and Health Outcomes

We aren’t quite finished with what the UPF evidence shows. However, based on observational data, consuming more than 30-40% of your energy intake as UPF is associated with negative health outcomes. Importantly, though, if you believe the observational data of an association with harm from eating more than 30-40% UPF, you also need to believe that almost all the harm is due to only two of the UPF food subtypes -- sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meat.

But there’s still one more thing you need to know—how all this risk applies to you. Read Part 3 tomorrow and see how the story ends.

James McCormack is a professor at UBC in pharmacy and medicine. He works to get useful evidence-based information out to the masses.

Please continue to post comments - once the 3rd part is released and people get a chance to review I'll respond and try to address many of the comments. Thanks for the interest and taking the time to comment.

I am really enjoying this series! I’ve started fielding a lot more questions about UPFs from friends and acquaintances. I’m a retired renal dietitian—was guiding my patients away from UPFs most of my career, because so many have higher sodium content and contain phosphate additives.