The Nutritional Cold War

PART 3: Should You Be Worried? Making Sense of Your Personal Risk

Today, James McCormack is back with the final part of his three-part series on ultra-processed food. He concludes by providing information on how individuals can assess their risk and make informed decisions about their own diet. We are indebted to James for the work he put in on this series.

Adam Cifu

I have saved the most important point until last. This is information rarely discussed or reported when evidence of the harms and benefits of what we eat is presented.

The evidence I have shared thus far has been population data presented as relative numbers. This is similar to seeing a sale sticker that says 30% off. If you don't know the original price, you can’t possibly know the actual cost or the actual savings. The same applies to these relative numbers reported from the observational studies: you can’t understand what your actual risk might be from eating UPF if you don’t know your baseline risk.

Let’s use meat as the example (focusing on processed meat), as it has been shown to be one of the two UPF subtypes associated with worse outcomes.

Zeraatkar et al and Vernooij et al reviewed 55 observational studies with over 4 million participants. They asked, what would be the difference in mortality, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes for an individual if they ate three fewer servings of meat each week?

The image below illustrates what a serving of meat was considered to be in these publications.

For processed meat, 50 g was considered a serving, equivalent to one standard hot dog or three pieces of bacon. For unprocessed red meat, a steak about the size of an average person’s palm, or approximately 120 g, was considered a serving. If the serving was a mix of processed and unprocessed meat, then 100 g was used. Because the typical North American and Western European diet consists of three servings per week, the difference evaluated in these publications would roughly correspond to what would happen if a typical meat-eating person eliminated red and processed meat from their diet.

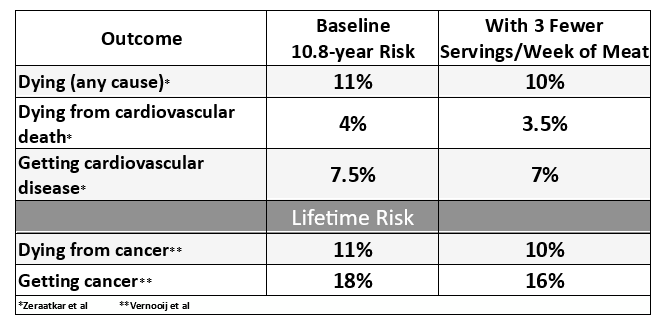

The findings are shown in the table below. A 3-serving-per-week reduction of unprocessed red meat or processed meat over approximately 10 years would be associated with a relative difference in overall mortality and cardiovascular disease of between 5% and 11%, as indicated in the grey row. While the relative numbers for unprocessed and processed red meat appear similar, remember that the definition of serving sizes for unprocessed meat was at least double those for processed meat. Therefore, a higher risk was observed for processed meat when comparing it gram for gram.

These authors then took these relative numbers and asked what would the benefit be for a middle-aged or older adult? Their estimate of the absolute difference is in the green row. When it comes to mortality and cardiovascular disease, the absolute difference is about 1%. Looking at this from a “number needed to treat” perspective, this would mean that 100 people would need to make this dietary change for 10 years to save one life.

Here is another way of looking at the effect on risk. The following table illustrates how relative risk translates to the absolute risk. These approximate 5-10% relative differences would equate to the following approximate change in your absolute risks of the following important outcomes.

The first number is your risk of an outcome if you didn’t reduce your meat intake -- your baseline risk. The second number represents your risk if you reduced your intake by three servings per week for 10 years. The numbers are derived by reducing the baseline by the relative difference observed in observational studies.

When these authors presented their results with these absolute numbers, there was considerable criticism of their conclusions. Interestingly, no one really criticized their specific numbers. Still, things got quite nasty, with one side saying these articles were “information terrorism” and the other side saying the response to the data “was completely predictable and hysterical”.

These are the numbers for unprocessed red meat and processed meat. When it comes to meat, there is always a further discussion about beef versus pork versus chicken, etc. The authors commented that they wanted to look at the effects of red versus white meat, but the studies they reviewed did not report sufficient information. For the study of cancer, the evidence didn’t even allow for a comparison of unprocessed versus processed meat, just overall meat intake.

The best evidence I could find and the best way I could explain it

This is the best I can do to illustrate the highest level of evidence regarding UPF and health outcomes.

The observational evidence for UPF clearly suggests the importance of dose.

If UPF accounts for less than 30-40% of overall energy intake, there does not seem to be much in the way of associated harms.

The observational studies on the UPF subtypes suggest the two main culprits are sugar-sweetened beverages and meat.

Unfortunately, the messaging around UPF is typically black and white. “UPFs need warning labels.” In my opinion, none of this sort of rhetoric can be justified by the evidence.

If you are eating less than 30-40% UPF and you enjoy what is presently being called UPF, great - eating should be a joy. The best evidence-based message I think we can give, when it comes to UPF, is that sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meat are the main, if not the only, subtypes associated with significant health problems. If you are truly concerned about UPF, focus on reducing those subtypes.

However, it really comes down to a personal choice about the magnitude of the problem. If a 1-2% absolute difference over 10 years is important enough for you to change the amount of meat you eat, make the change. If that difference sounds small, and if you really enjoy meat, don’t make a change. Once you are properly informed, you should make your own decision.

Of note, I have not touched on the ethical or environmental reasons to eat less meat — those may matter much more to you than the health outcomes. For me, the animal rights issue is why I don’t eat red or white meat, not the health reasons.

Some people will say that we need more studies. Although RCTs would be wonderful, when it comes to the best available evidence of the health impact of food, we are pretty much stuck with observational evidence. We have a lot of that already. Having yet another single observational study is not going to change the ballpark numbers presented. What might be useful are observational studies that look at subgroups of food to tease out a more nuanced view at what we eat.

What we desperately need are the results of the information we already have presented clearly, without the rhetoric, so you can be properly informed and make up your own mind about food decisions. When it comes to food wars, the most effective way to win is by understanding what the best available evidence indicates about the benefits and harms. Blanket attacks on entire food groups aren’t helpful — and the joy of eating should never be acceptable collateral damage.

Thanks to a number of my colleagues and friends and family for helpful reviews of this rant and to ChatGPT for some of the clever titles.

James McCormack is a professor at UBC in pharmacy and medicine. He works to get useful evidence-based information out to the masses.

Very informative. Giving people absolute risk data on UPF’s and highlighting personal choice is what is needed. I personally stay away from them but if I want something I’ll eat it. Moderation is important. Thanks for the great series.

I’m sensing that Big Nutrition has figured out how to keep the money coming. Failure on their part to make any positive difference in health outcomes doesn’t deter them from the use of observational studies in forming useless dietary recommendations. So now on to UPFs. Acknowledging that observational studies are weak but the “best we can do” doesn’t make them worth anything at all. The nutrition industry needs to extricate itself from the failed paradigm of calories in and out and instead concentrate its efforts on understanding the biology of the fat cell.