The Problem with Pragmatic Trials

The study of the week explores the challenges of extracting knowledge when trials mimic the noisy world of clinical practice

Today we talk about the environment and procedures of a trial and how it affects translation of the results to patients.

Think of two extremes: one trial requires that patients stay on their assigned strategy with no deviations; the other trial allows oodles of physician discretion and crossover. The latter trial is called pragmatic. Keep in mind though that pragmatism is not dichotomous, all trials have degrees of pragmatism.

But for the sake of argument, today we consider the extremes—highly restrictive vs highly pragmatic.

The restrictive trial allows one to assess performance of the treatments. The con is that it is unrealistic because practice does not work that way. The upside of the pragmatic trial is that because it mimics practice it is more generalizable. The negative is that physician discretion and crossover creates noise so it’s harder to sort effects from the two treatments.

JAMA has published the A2B trial of three types of drugs for sedation in intubated patients in the ICU. You don’t have to be an ICU doctor to learn from this trial.

Basic facts: patients on ventilators need some sort of sedation. Numerous drugs can be used. There is debate about the best drug. The most common drug is propofol—known for its milky appearance.

Propofol has some downsides, so a group led by a team in Edinburgh Scotland designed a three-way comparison of dexmedetomidine, clonidine vs propofol. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine are called α2-adrenergic receptor agonist–based sedation agents. (You might recognize dexmedetomidine by its brand name of Precedex.)

Just over 1400 patients were enrolled if they were expected to be on the ventilator for more than a day.

Trial procedures were the key factor. The trial was open-label, and the docs adjusted the dose according to how much sedation patients needed. Extra doses of propofol were allowed in the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist–based sedation groups as determined by physicians. Trial protocols guided extubation protocols, but again, doctors used big doses of judgement.

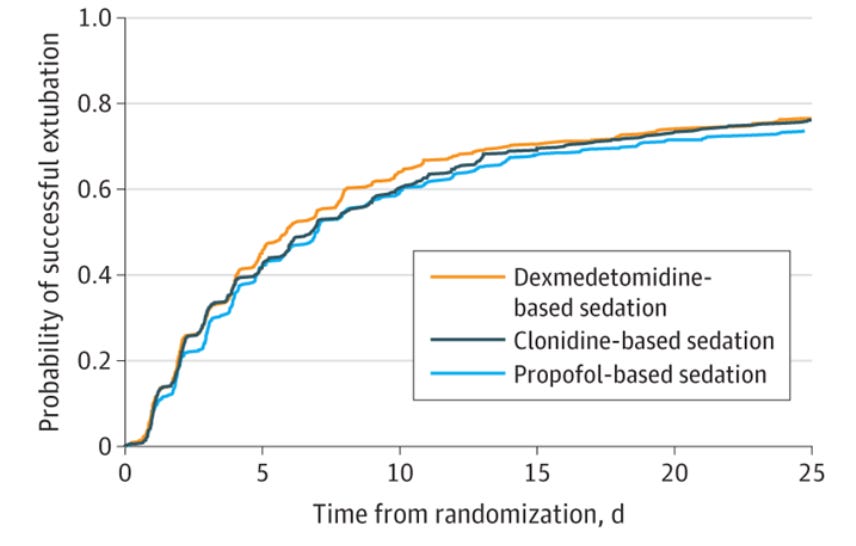

The primary outcome was time from randomization to successful extubation. Secondary outcomes included mortality at 6 months, measures of sedation quality, rates of delirium and cardiac events. The pretrial theory was that the non-propofol drugs would reduce time to extubation.

Results:

The short story is that there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of time to extubation compared with propofol. Time (in hours) to successful extubation was slightly shorter in the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist groups. The relative differences are below.

HR for dexmedetomidine vs propofol was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.96-1.25; P = .20);

HR for clonidine vs propofol was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.95-1.17; P = .34)

No significant interactions were observed for the predefined subgroups of patients.

Secondary outcomes were notable.

Agitation occurred 54% more often with dexmedetomidine vs propofol (HR 1.54 CI 1.2-2.0) and 55% more often with clonidine vs propofol (HR 1.55 CI 1.2-2.0).

Bradycardia was also more common with dexmedetomidine (RR, 1.62 CI, 1.4-1.9) and clonidine (RR, 1.58 CI, 1.3-1.9).

Mortality at 6 months was similar in the three groups

The trial authors concluded:

In critically ill patients, neither dexmedetomidine nor clonidine was superior to propofol in reducing time to successful extubation.

Comments:

Let’s say you are an ICU doctor or informed patient. What is the conclusion from this trial?

Do you say, “yep, this proves it. Stick with the old standby propofol.” The α2-adrenergic receptor agonists don’t work any better. What’s more, sedation quality was worse in the non-propofol arms.

Or, you might conclude, since there were no differences in the primary outcome, either of the three approaches are fine.

The main tension, and the reason I highlight the trial, was the highly pragmatic features of the trial.

First, the trial was open-label, which is important because doctors may treat patients differently knowing their treatment assignment. Specifically, comfort with extubation (the primary endpoint) may be different (less) with propofol infusions.

Second, patients in the dexmedetomidine and clonidine groups were allowed to receive propofol doses to achieve proper sedation. And more than 75% of patients on the α2-adrenergic receptor agonist–based received lower doses of propofol. Clinically, THIS IS FINE, but from a trial point of view, it creates added noise because the sole way the two α2-adrenergic receptor agonists reduce extubation time is by allowing patients to have lighter sedation and less respiratory suppression.

Do you see the problems?

The open-label aspect is really problematic because it allows different clinician behavior. Yet there is almost no way to blind 1400 patients in an ICU when one medicine is milky white and the other meds are clear. So you do the trial and accept the noise.

As for sedation protocols allowing crossover, you allow this because it mimics practice and increases the ability to enroll patients. If you told patients (and their doctors) there was no possibility of switching arms, they might not want to participate. So you do the pragmatic trial and accept the noise.

In the end, as an outside observer, I am not sure we get a definitive answer. I think good-old propofol holds up pretty well.

As the editorialists write, perhaps we don’t get a definitive answer because there is not one. Maybe there is no single best sedative agent. And maybe we should stop trying to find one, accepting the fact that the best sedation protocol requires skilled clinicians mixing and matching based on the situation.

I sort of like that conclusion. But we would not know this without the A2B trial. So good on the team from Edinburgh.

Nothing is said here about the most important factor. What were the negative factors of using Propofol that led to the trial even being done? And were those negative factors measured in the different arms to see if there was improvement?

Does it matter at all how many and what drugs the patient is already taking?