The PSA Screening Test and Humility

NEJM publishes 23 year results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer trial. Only one word comes to mind: humility

I am old enough to have had a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test discussion with my doctor. I initially refused but in a recent moment of weakness gave in.

The 23-year follow-up results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial (in NEJM) reinforces my initial opposition to being screened with a PSA test.

ERSPC was a multicenter randomized study conducted across eight European countries in more than 160,000 men aged 55-69 years. The active arm was offered repeat PSA testing and the control was not invited to screening.

The trial began in 1993 and has previously reported at nine, eleven, thirteen and sixteen years. The primary outcome of this trial has been prostate cancer mortality. The relative risk reduction from screening in each of these trials was about 20%.

I will discuss the absolute risk reductions, effect on cancer detection and overall mortality.

Before I show you the 23-year results, let’s do some basic facts about prostate cancer in the US. It’s the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men, but it is not a common cause of death. About 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during their lifetime, but only about 1 in 41 will die from it.

Older autopsy studies have found that a very high percentage of elderly men who died from other causes had prostate cancer they never knew about. The screening dilemma is the presence of aggressive prostate cancers which can affect younger men and would be great to catch early. The problem is that PSA tests cannot distinguish the slow-growing from aggressive forms.

The 23-year ERSPC Results

After 23 years, the prostate cancer mortality was 13% lower in the screening group (Rate ratio 0.87 95% CI 0.80-0.95).

The absolute rates of prostate cancer deaths were 1.4% vs 1.6% in the screened vs control arm. So the absolute risk reduction was 0.2%. This means that the number needed to screen to prevent one prostate cancer death is approximately 500. I like to think of this as: 499 out of 500 men get no benefit from being invited to be screened.

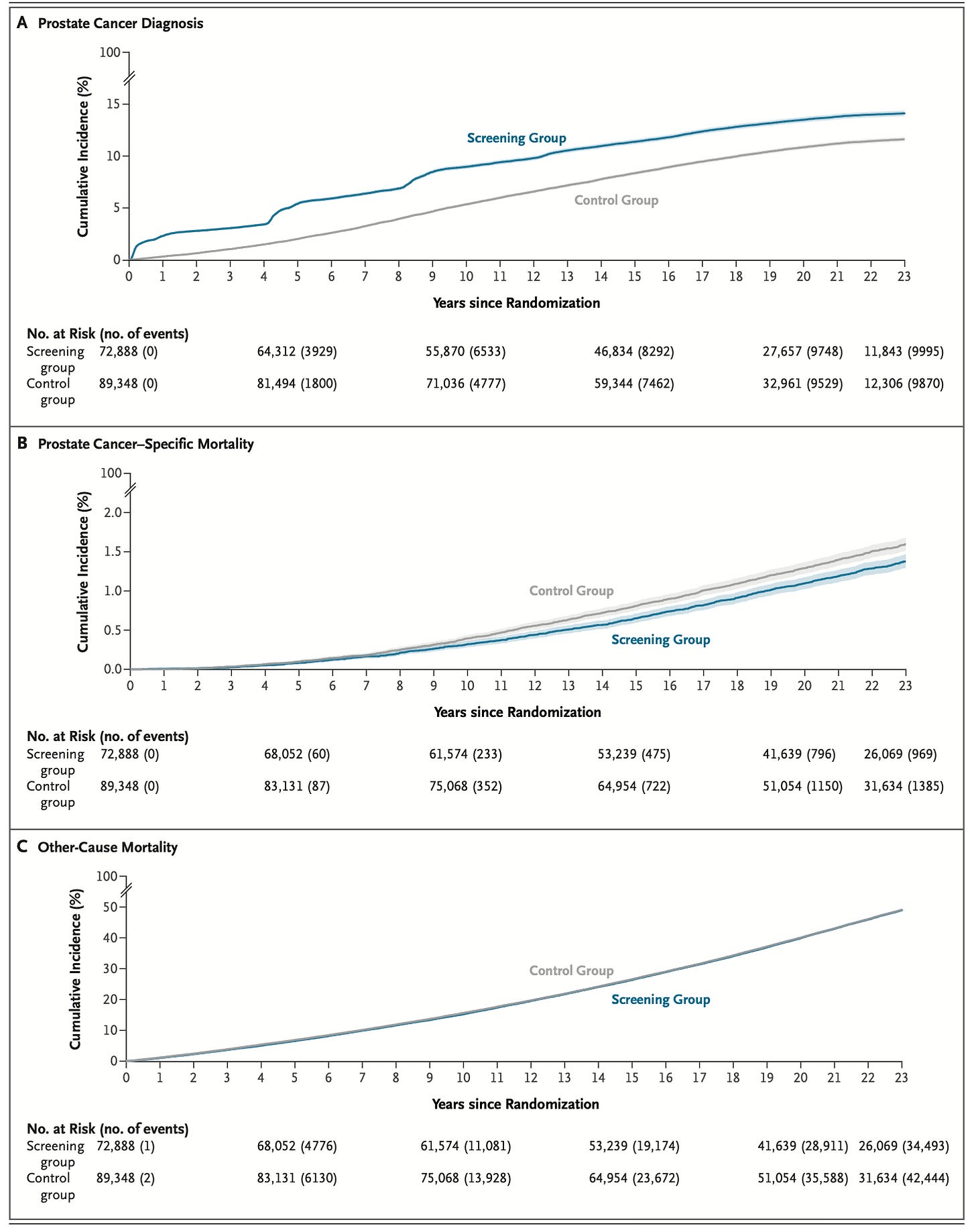

Here are graphic representations of the results. Pay close attention to the different y-axis.

Screening detects 30% more prostate cancer, though on an absolute scale it is only an excess of 27 cases of prostate cancer per 1000 men. A supplemental figure shows that screening is 2x more likely to find low-risk cancer, and 44% less likely to find high-risk cancer.

The curves for prostate cancer mortality are on a y-axis of 0-2%. Imagine them on a scale of 0-100%. In absolute terms there is—essentially—no difference.

The overall mortality curves are identical. Prostate cancer detection does not prolong life. That is because other-cause mortality is 49% in both groups.

Comments

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives PSA screening a C-grade, which means net benefit is small and it may be offered to selective patients based on professional judgement or patient preferences.

I struggle with this—based on this data. ERSPC found a minimal absolute risk reduction in prostate cancer deaths (0.2%), no difference in overall mortality, and we know that there are potential complications from biopsies and surgeries.

This data illustrates Wilson and Jungner’s 1960s-era declaration of screening: screening for disease is admirable but in practice there are snags.

The snags of PSA screening from this study are a) at baseline, prostate cancer is rarely deadly and often slow-growing, b) screening is most likely to pick up low-risk tumors, c) older men are many times more likely to die of other causes, and d) once a PSA is positive it is hard not to act, and action can result in complications, such as incontinence and impotence.

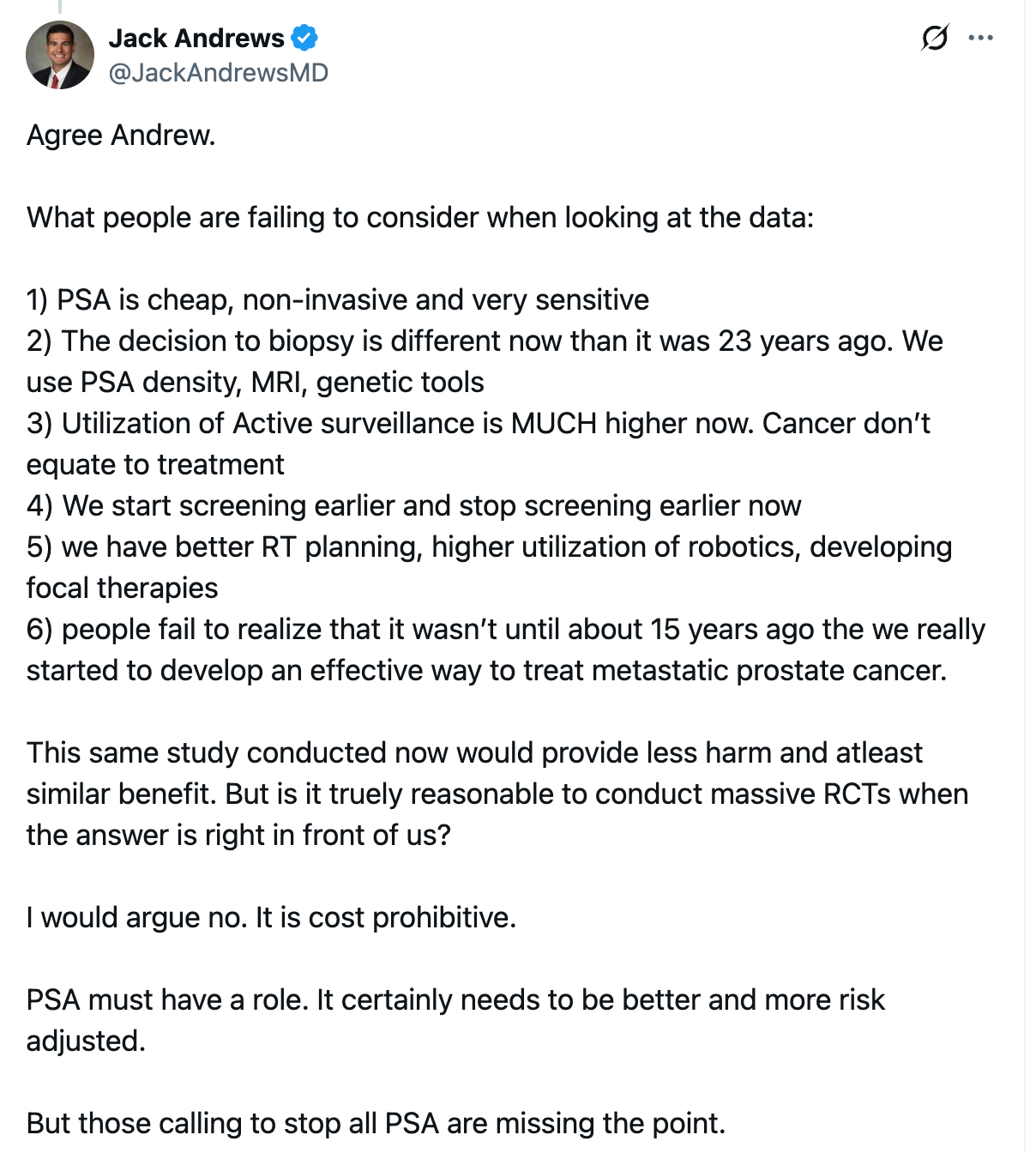

In fairness I want to highlight this post on X from a urologic oncologist. Dr Jack Andrews writes:

As a non-urologist I cannot contest these comments.

I can only speak from the Neutral Martian and patient perspective.

Namely, that having a positive PSA would be a buzzkill. You would worry about it. You would have to go to for MRIs, genetic tests, etc. Maybe you could avoid a biopsy. Maybe not.

In the absence of better effect sizes on reduction of mortality, my minimizer-brain, sees the 9,999 other diseases that could take me out. And I would pass on PSA screening.

A maximizer brain might think otherwise, and that is fine. But I would hope doctors discuss this data with their patients. And would be humble about how much we can “prevent” bad outcomes in people without complaints.

I am curious what you all think.

As an oncologist, I'm inclined to follow the data which in this case is that PSA screening doesn't impact mortality. As in breast cancer and other cancers, improvements in survival are mostly due to better therapies for metastatic disease, not early detection.

If prostate cancer treatment is better now, that should mean the need to screen has declined.

That urologist even hints at it in his tweet:

“We get the PSA, do a bunch of tests and then we put that prostate under active surveillance. Look at us, actively watching! So much benefit provided, sure glad we picked up that cancer so we could watch it, hopefully for years and years.”

Seems like minimal survival benefit, you’re looking for special cases of prostate cancer where early detection actually makes a difference to survival.