The Surprising Ability of Medical Therapy in Coronary Heart Disease

A look at the STITCH trial. It's a shocker

This winter I showed the seminal trials comparing coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) vs medical therapy. These were done in the 1970s and 80s. Two of the big three trials found no mortality benefit from CABG. Most of these patients had normal ventricular function.

Along with my colleagues Andrew Foy and Mohammed Ruzieh, we have recently reviewed these trials over at the Cardiology Trials Substack. Last week, we included a review of the STITCH trial. It’s one of the most surprising trials I have seen in my career. It’s worth another quick summary here. The teaching points extend beyond cardiology.

NEJM published STITCH in 2011. The main hypothesis was that CABG would outperform medical therapy in patients with severe coronary disease and impaired ventricular function.

One of the core ideas in cardiology is that improving blood flow to a heart with severe reduction of flow due to coronary stenoses will improve outcomes. The medical jargon of that sentence is…revascularization benefits patients with ischemic heart disease.

The addition of patients with a weak heart muscle makes it even more likely that improvement of blood flow should improve outcomes—over medical therapy. I put the last phrase in italics because medical therapy had expanded greatly between the first generation CABG trials and recruitment for STITCH. We now had disease-modifying medications.

The STITCH Trial

The trialists randomized about 1200 patients who had severe CAD and LV systolic dysfunction to either CABG or medical therapy. These were young patients (age 60) and nearly 90% were men. More than 80% were on beta-blockers, ACEi or ARB and statins. More than 85% of both groups had Class 2 or 3 heart failure.

Most important was the LVEF. The median EF was 28%. We consider this a moderate-severe amount of heart muscle weakness.

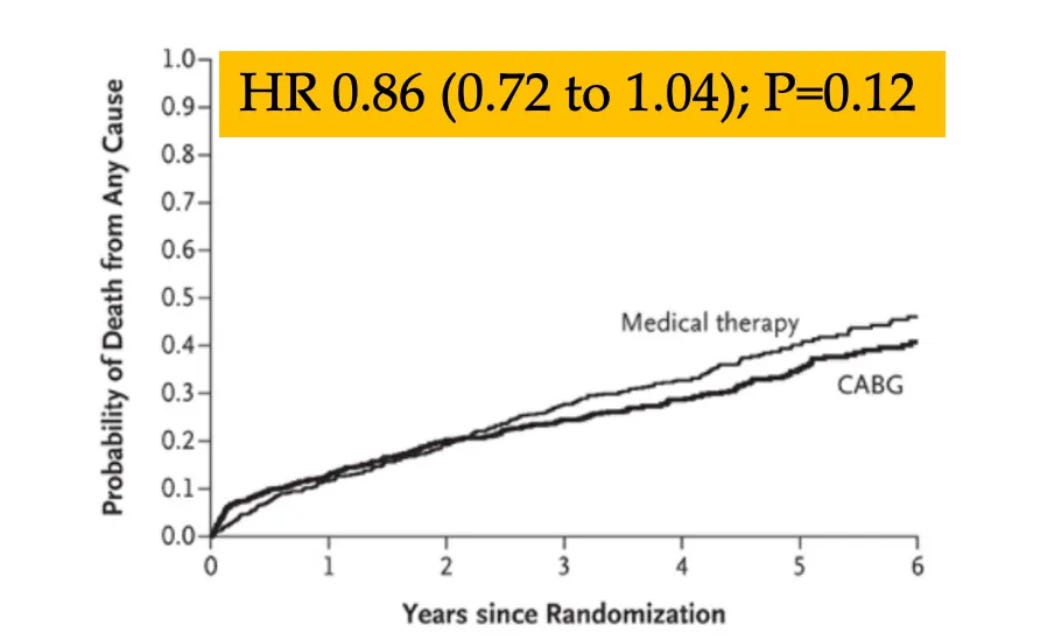

Over 5 years of follow-up, the authors reported no significant difference in the primary outcome of all-cause death. Death occurred in 41% of those in the medical arm vs 36% in the CABG arm. The graph below shows the survival curves.

The authors reported that no subgroup had a significantly different result from the overall result. Not those with more HF; not those with more angina or those with diabetes, or those with severe mitral regurgitation.

Comments:

The surprise of this trial comes when you picture the angiograms and echocardiograms of these patients. When you see the picture of these angiograms, you think, ouch, that looks really bad. Couple that with a weak heart on ultrasound.

Fourteen years after this trial, it would be daring to put this sort of patient on a few tablets, and not bypass those stenoses. I can’t say what it is like in other cities or countries, but in my experience, these patients get the stenotic lesions bypassed or stented.

Heck, I might want that myself, even though I’m decent at reading trials.

Yet the results are clear. The survival curves are nearly identical. Statistical purists might argue that the trial was underpowered. The 14% reduction in death may have met statistical significance if there were more patients. The lower bound of the 95% confidence intervals allows for a 28% reduction in death.

But trials are what they are. And with 1200 patients and a bunch of events, there is not a significant reduction in death.

The teaching point is that despite evidence—the mostly negative primary CABG trials, and STITCH—cardiologists continue to undervalue medical therapy over revascularization.

Maybe it’s the images that scare us. Maybe it’s the way we trained. Maybe it’s the idea that white tablets couldn’t possibly be as good as surgical (or stent) therapy.

To me, STITCH shows the value of medical evidence and RCTs. I would have never guessed that medical therapy could perform so well against surgery in patients with such advanced heart disease.

It reminds me of the Richard Feynman quote:

“the first principle of science is that you most not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

I like to think of trials like STITCH when I hear colleagues say that we cannot study something because we know it works. Grin. JMM

Footnotes:

My surgical friends would point to the STITCHES trial, which is the 10-year results of STITCH. STITCHES reported a similar 16% reduction in death with CABG that now reached statistical significance. But it’s a small difference: in a trial of 1200 patients, the difference in death was only 39 patients.

For a more complete review of STITCH, head over to Cardiology Trials substack where we intend to summarize all the major cardiology trials.

I am not a cardiologist, but I seem to remember being told that beta blockers don't improve mortality. They improve blood pressure (and reduce heart rate, of course). People don't live longer, they just die with "normal" blood pressure. Does this then imply that neither beta blockers nor surgical intervention improves mortality? Yes, I realize that it was not just beta blockers that were given to people in the medical arm of this study.

I wonder about the effective of much of what we offer as medical providers. It would be nice if there was a non-medical, non-surgical arm of the trial where people were coached on exercise appropriate to their health and coached on nutrition. That being said, if I was the patient, I would probably opt for an intervention of some sort out of fear. Which just goes to show the power that doctors have over patients in poor health.

In addition to deaths, I'd like to know if there were significant differences regarding quality of life between the two groups?

Were there any significant differences between the groups on how far they both able to walk without getting breathless. Did one group require more oxygen support, more "rescue" hospitalizations due to pulmonary edema, ascites ... ?

It's one thing to be alive and able to get out for a mile walk without stopping and another to be alive but housebound while tethered to an O2 generator with low quality of life.