The Trouble with Treating the Future: Elevated Lipids, Low Risk, and the Making of Patients

Dr Piessens is a GP in Belgium who argues against using a 30-year timeline for heart disease risk

I particularly love this persuasive argument against using a 30-year risk time frame for heart disease prevention. What makes this piece so good is the mixture of data and philosophy. JMM

Is a 10-year time frame too short to decide whether to start lipid-lowering medication, or should such decisions instead be based on a person’s projected 30-year risk?

In younger individuals, the 10-year risk will always be relatively low, even in the presence of markedly elevated LDL cholesterol levels. The argument, however, goes that atherosclerosis is a chronic process, and the longer people are exposed to elevated LDL-C, the higher their lifetime risk of ischaemic events. Hence, the call to start lowering LDL levels at younger ages, to prevent plaque formation and reduce risk later in life.

In practice, lipid-lowering medication is often started without a comprehensive assessment of overall cardiovascular risk. When total risk is considered, advocates argue that a 30-year horizon provides a more realistic risk assessment than a 10-year one. Or does it merely produce a more frightening risk estimate because the numbers are higher?

While it may seem logical to modify risk factors early in life to halt the underlying pathophysiological process and improve future health, this approach raises serious medical and ethical concerns. It ignores the fact that there is no such thing as zero risk. It represents a regression to the single-risk-factor approach of decades ago. It medicalises a laboratory measurement and turns healthy people into patients. Most importantly, we lack empirical evidence showing that early lipid-lowering in this population confers meaningful benefit over such long time horizons.

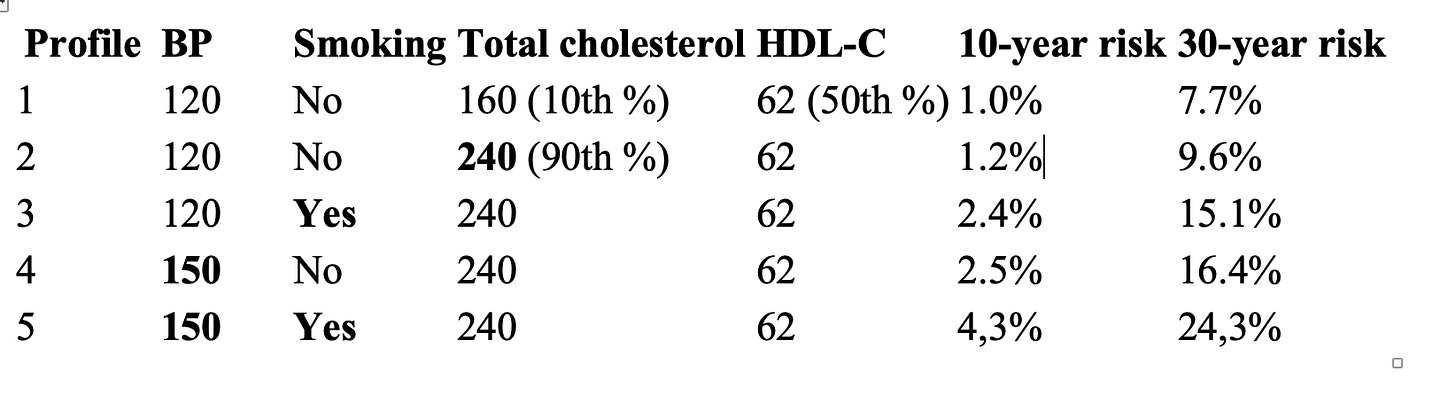

But how large is the additional risk associated with elevated lipid levels in younger people? Below are simulations using the PREVENT® calculator for a 45-year-old woman, assuming normal kidney function, and an HDL-C at the 50th percentile. Profile 1 represents naturally low lipid levels (10th percentile), and profile 2 high lipid levels (90th percentile). BMI appears to have no effect on the PREVENT risk estimates.

With low lipid levels and no other risk factors, 7,7% of women will nevertheless have experienced a cardiovascular event by the age of 75. There is no zero risk. The absolute risk difference between women in the highest 10% of natural lipid levels and those in the lowest 10% is approximately 2% over 30 years. Only for these 2% of women might early lipid-lowering medication theoretically make a difference.

Even if we were to believe that medication-induced lipid-lowering could reduce their risk to that of people with naturally low lipid levels, this would still mean that 98% of women with high lipid levels would undergo decades of treatment without any chance of benefit. Moreover, we do not have a single study demonstrating that such a benefit exists in this age group, at such low baseline risk, let alone over a 30-year horizon.

For statins, the JUPITER-trial is the primary prevention trial with the lowest baseline risk. Yet, the mean age of participants was 66 years, and the baseline risk of MI, stroke or CV death was 0,85% per year, equivalent, when liberally extrapolated, to at least an 8,5% 10-year risk. This is many times higher than the risks simulated here. For ezetimibe, there are no robust primary prevention trials at all. The population enrolled in the recent VESALIUS-trial with evolocumab likewise had a mean age of 66 years, and a 4-year baseline risk of 8%, despite background statin and ezetimibe treatment. Hardly representative of a young, healthy 45-year-old woman.

Only the accumulation of several risk factors (profiles 3 to 5) results in a markedly elevated projected 30-year risk. In these cases, lipid-lowering may be a reasonable strategy to mitigate future risk. However, the evidence remains lacking, and smoking cessation or blood pressure reduction may be more appropriate initial steps.

The enthusiasm to medicalise healthy people based solely on pathophysiological reasoning and observational research is troubling. Despite their sophisticated label, Mendelian randomisation studies remain observational and cannot provide evidence that pharmacologically lowering lipid levels will reduce future risks. Have we learned nothing from the long history of medical reversals? Each reversal was once a seemingly logical and well-argued established practice, largely grounded in observational data.

Exposing healthy people to thirty years or more of medical treatment demands strong evidence. This is not about encouraging people to eat healthily, exercise adequately, or quit smoking. Practices that should be promoted universally, irrespective of LDL levels. The issue here is medicalising healthy people and treating their laboratory results as a disease. This draws people 15 years earlier into the Kingdom of the Sick1, and shapes them to fit in the machinery of surveillance medicine.

People experience no symptoms from elevated LDL levels. The only way to motivate them to approach this medically is by urging them to live their present lives under the shadow of future health threats. Apart from the questionable ethics, this is also difficult to achieve, as most people prefer to live in the here and now. To overcome this inconvenient ‘lack of urgency’, risk factors have been elevated to the status of diseases, with measurements replacing symptoms and numbers treated as if they were illnesses.

This disconnects people from their own lived experience of health and sickness, and transfers the authority to decide on who is healthy to the technico-medical complex. Meanwhile, healthcare professionals spend countless hours monitoring and adjusting treatments for risk factors, consuming time that could be devoted to cure and care[1]. Healthcare expenditures continue to rise, and we quietly allow the pharmaceutical and food industries to scratch each other’s backs and distort what healthy living is supposed to mean.

While we await solid evidence to support lipid-lowering treatment in young, healthy people, let us focus on those who are already ill or genuinely at high risk, for whom benefit is not hypothetical but proven.

Footnote:

* In her essay ‘Illness as Metaphor’, Susan Sontag describes becoming ill as a migration from the Kingdom of the Well to the Kingdom of the Sick.

Veerle Piessens works as a GP in a community health centre, and as a teaching assistant at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of Ghent University, Belgium.

Dr Piessens -- Excellent points. The topic of your PhD is extremely important in our overmedicalised age. Here's how I see the dynamic:

-- The drug company (and their generously compensated researchers) has the incentive to expand those carrying a given diagnosis.

-- Thus, as the number of 'patients' grows without end, the marginal benefit of a given intervention gets ever smaller.

-- Marginal harms of including vast numbers of the low-risk population grow ever larger.

-- At some point the 'lines cross' and there is net harm, both at the individual and population perspectives.

As well illustrated with cholesterol treatment already sanctioned by medical bodies, vast resources go toward useless, even harmful, treatments because of some lab result.

--Thank you for your work.

After 50 years of practice I have come to the same opinion. If Life style was a product of Big Pharma it would be easy to implement it.