The Universal Language of Clinical Medicine: A "Foreign" Doctor’s Perspective

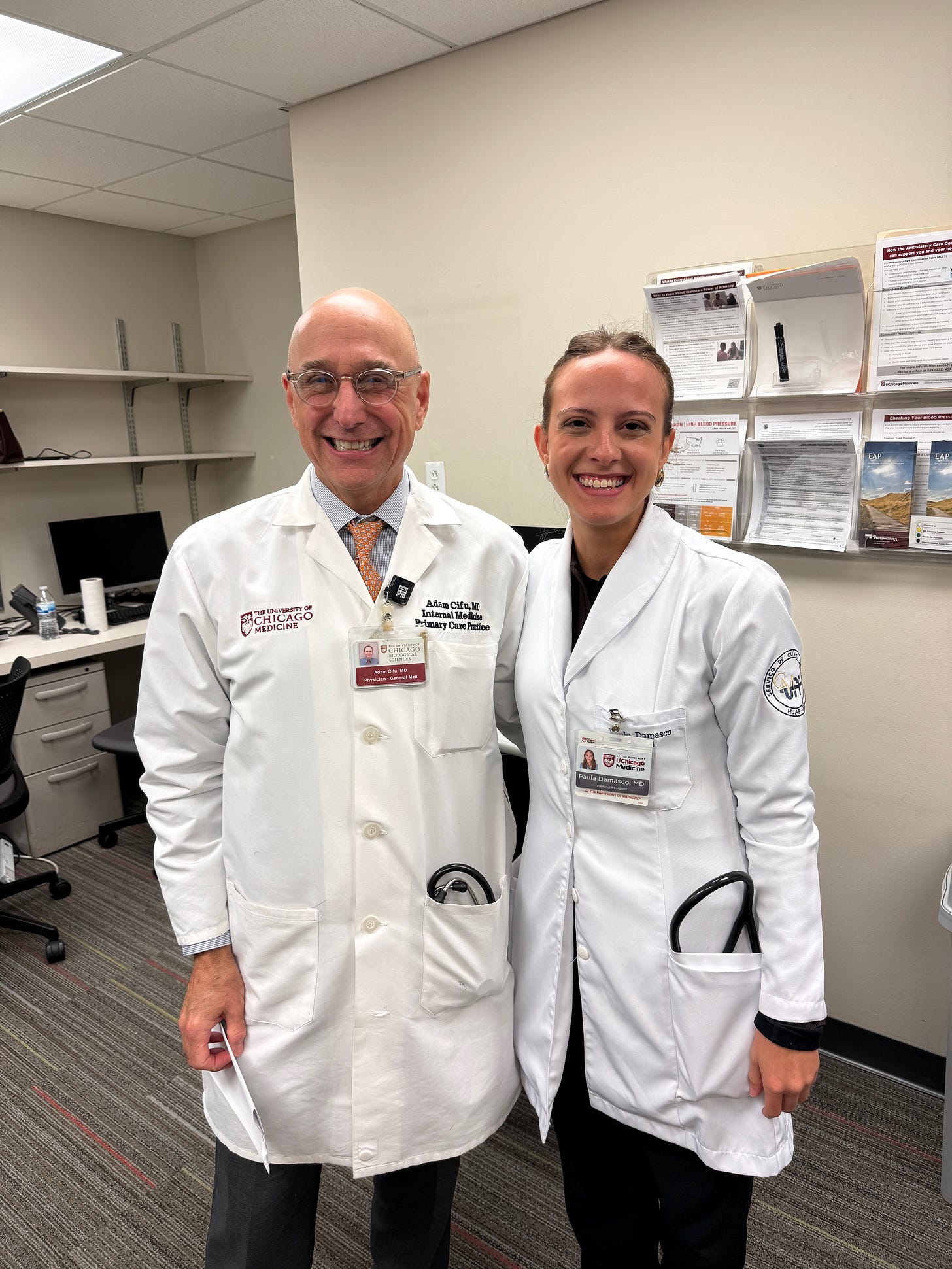

Paula Damasco is an internal medicine resident from Brazil who worked with me last month. I was impressed by her knowledge, her patience, and her insights as she watched — and critiqued — medicine practiced in a foreign culture, language, and country. I hope she learned as much from us as I learned from her.

I asked her to write a reflection about her experiences shadowing me and my colleagues in Chicago.

Adam Cifu

I am a physician from Brazil currently completing my final year of training to become a primary care physician/generalist. I wanted to spend a month rotating with Dr. Cifu because his position and practice are similar to those of my mentors in Brazil, and I was eager to learn from someone with this experience. I am also interested in how this approach to primary care is implemented in the United States.

From what I’ve gathered, the universal language of clinical medicine is care. My time in Chicago has only reassured me that this is where all of us—across the specialty—converge.

Throughout my relatively short career, I’ve come to realize that generalists are at the heart of medicine. They coordinate tasks from health care maintenance to complex diagnoses.

We listen attentively, make sense of the information, and then translate that into care. In this process, we know when to zoom in with a magnifying lens and when to step back. From this perspective, one skill we frequently use is identifying outliers.

In clinical reasoning, an outlier refers to a case, symptom, or presentation that deviates from the typical or expected patterns seen in most patients with a condition. These cases are unusual or atypical and often don’t fit the standard diagnostic or treatment protocols clinicians typically rely on.

Identifying outliers depends on another primary care feature: knowing our patients. A primary care doctor might follow a patient for 30 years—longer than I’ve been alive. Over this time, we witness lives pass through active years to inevitable decline. This enables us to recognize the outlier. We develop profiles of each patient’s mindset to determine the best approach. Every patient has a unique relationship with us, and sometimes we need to guide them toward the right decision. Simply telling them what to do isn’t enough; they need to arrive at their own solution.

Additionally, a key feature of the primary care physician is availability. We are just one call away, always there for reassurance. In this sense, I feel like we’re often “anxiety takers.” Patients seek our judgment to help them navigate their concerns and validate their health worries.

Another distinguishing characteristic of our role is that we often know not only the patient but also their family and life history. Sometimes, patients even see us as part of their family, to the extent that they want to ensure we know everything about their lives.

From my perspective, we tend to be conservative—not in a political sense, but in how we approach patient care. This might be a controversial topic, but it’s what I’ve observed over the years. This conservatism relates to our clinical set points—a term I have to credit to Dr. Cifu’s Friday Reflection 20:

”Clinical set points are an extension of our personalities, a combination of genetics and life experience, much like why some of us are extroverts and others introverts.”

I’ve come to realize that generalists come close to “having seen it all” and understand the complexities and nuances of healthcare. This experience teaches us the importance of taking a cautious, thoughtful approach with each patient. In this role, we help patients navigate their care path, guiding them on what to pursue and what to avoid. It’s often about balancing clinical evidence with their well-being. Perhaps because our lens is the same as our patient’s, we tend toward minimalism in our approach—doing just enough to help without overcomplicating things.

Though used throughout medicine, the “problem list” is probably most important to the generalist. The problem list is a concept initially proposed by Lawrence Weed. The components of a well-constructed problem list provide a disciplined method for structuring clinical reasoning and connecting it to external knowledge sources. This integration allows clinicians to move from raw clinical data to organized problem lists, and from there to evidence-based hypotheses and management options. I come to see this as a key element of good care. It supports clinical reasoning, follow-up, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Every physician has their own way of approaching it, but overall, the problem list serves as a guide to delivering effective care.

Finally, at the end of the day, primary care physicians just want to do the right thing, at the right time, in a way that feels right.

There’s only one way for this to happen: study, discipline, suffering, and principles.

And what are these principles? First, to avoid suffering. Then, insistence, persistence, and initiative. And finally, observation that leads to reflection, which in turn leads to clinical reasoning and good care.

Acknowledgement. I give special appreciation to my mentors in Brazil who taught me these principles and inspire me every day.

Paula Damasco, MD, is a second-year resident in Internal medicine at Antônio Pedro Hospital, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Photo Credit: Paula Damasco

“Finally, at the end of the day, primary care physicians just want to do the right thing, at the right time, in a way that feels right.

There’s only one way for this to happen: study, discipline, suffering, and principles.”

Excellent. 👍

Dr Damasco - your essay is inspiring! God Bless you and I thank God there are still in this world physicians like you. And I hope that others reading your essay recognize that the medical arts are alive and well in places other than ‘the West’…