Using Evidence Requires Caution

The Study of the Week explores how results from seminal trials may not apply to older patients with frailty

This column has long celebrated the value of evidence, especially that from randomized trials. Without evidence, doctors can easily be fooled.

One challenge, however, is applying trial results to the patient in front of you. We call this the translation of evidence.

JAMA-IM has published a super-important trial that gets to the heart of this challenge.

The problem at hand is the treatment of patients who present with a kind of heart attack called a NSTEMI, or, non-ST-elevation-myocardial infarction. Don’t get bogged in the jargon. In essence, this is a common type of heart attack that has a specific appearance on an ECG.

We use two general treatment strategies—an early invasive approach in which patients go to the cath lab and if there is a culprit blockage, the doctor stents it open. The conservative strategy includes treating the patient with drugs that block clotting and then going to cath lab if there are recurrent symptoms or a high-risk stress tests.

The seminal trials are mostly neutral on the two strategies. There is a trend toward greater benefit in the early invasive approach for high-risk patients. The favored approach—in general—is early invasive.

The tension comes in that the foundational trials included few older patients with co-morbid conditions, such as frailty. And there is good reason to think that evidence generated in non-frail patients may not apply to the frail.

Enter the new trial from Spanish investigators. They did something unusual but extremely helpful. They enrolled only older adults with frailty who came to the hospital with a NSTEMI-type heart attack.

Yet this was not the only novel thing these investigators did. They chose a novel primary endpoint. In addition to measuring major adverse cardiac events (or MACE), they also measured as a co-primary endpoint the number of days alive and out of the hospital after discharge.

In 13 centers in Spain, 167 older patients with NSTEMI and high frailty scores were randomized to either an early invasive or conservative strategy. The mean age of patients was 86 years old.

Results

The trial had to be terminated early due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the number of days alive and out of hospital was nearly a month longer for those in the conservative arm.

Survival was 28 days shorter in patients managed with the early invasive strategy.

The more typical endpoint of major adverse cardiac outcomes did not differ between the two groups.

The authors concluded:

…there was no benefit to a routine invasive strategy in DAOH during the first year. Based on these findings, a policy of medical management and watchful observation is recommended for older patients with frailty and NSTEMI.

Comments

The first tension involves baseline risk and benefit. The seminal trials have shown a trend to better outcomes for the invasive strategy in higher risk patients.

This might lead you to believe there is no limit to the association—the higher the risk, the greater the benefit of the invasive strategy. But this is unlikely to be true. If you get to a high enough risk, due to age, or frailty, or both, things get more complex.

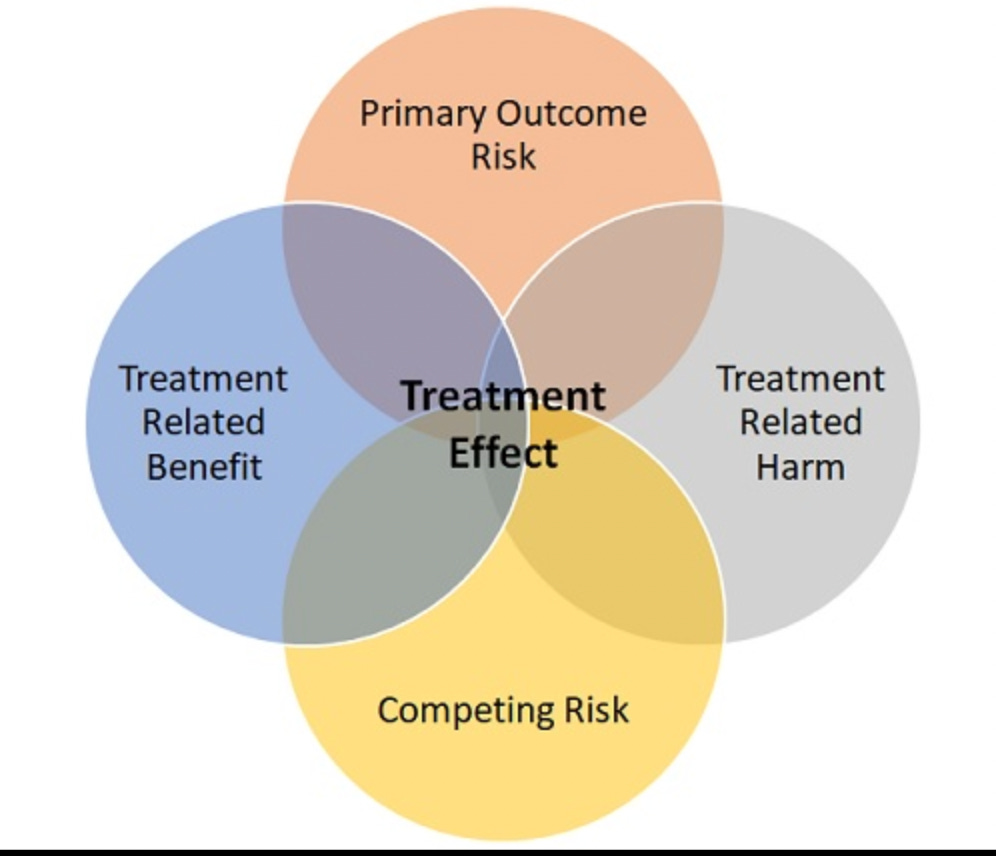

This figure, from Andrew Foy, a friend, mentor, and co-author of the accompanying editorial for this paper, depicts why an older patient with frailty may not garner the same benefit from an invasive approach to NSTEMI as a younger more typical high-risk patient might get.

Treatment effect (invasive vs conservative) turns on at least four of these domains.

Start with the vertical axis: an 86-year-old clearly has a high risk of dying or being re-hospitalized after a NSTEMI, but she would also have competing risks of many other diseases. So…even if an invasive approach was substantially better than a conservative approach for preventing cardiac issues, 86-year-olds have many other reasons to be get into trouble—falls, bleeding, cancer, infection, etc.

The horizontal axis depicts the tension between benefits and harms of the treatment. The invasive strategy may have the benefits of early opening of the artery, but it comes with potential harms—such as procedural complications or bleeding. An 86-year-old may be higher risk from a NSTEMI, but she may also be more susceptible to a treatment-related harm.

(The novel endpoint of days alive and out of the hospital after discharge incorporates some of these tensions. Foy and his co-author explain in the editorial that this endpoint holds promise for older patients with complex medical conditions.)

When you exclude older frail patients from trials, you are left with uncertainty. Pessimists would point to Foy’s figure and say it’s unlikely that treatment benefit translates. Optimists would argue that we should not deny older patients the benefits seen in younger patients.

That is the beauty of this Spanish trial. While there were statistical limitations due to early termination of the trial, there was a strong signal of benefit from the conservative strategy.

And.

These results clearly differ from previous studies which led to the accepted standard of preferring the invasive approach.

The teaching point is that we should not assume that trial results obtained in younger more ideal patients applies to older patients with co-morbid conditions such as frailty.

The picture of the four domains affecting treatment explains why results may not apply to older patients, but this trial shows that it actually does differ.

Finally

There are no absolutes in translating trial results. It requires skill and clinical judgement.

The Spanish trial shows that treatment effects are not universal in all patients with the same diagnosis. But we should also not assume that trial results apply narrowly to patients exactly like those in trials.

The answer, I think, is humility.

We need more trials. Trials in older patients with co-morbid conditions. Trials with broader inclusion criteria.

And a mindset that trials are the foundation of knowing in medical practice.

I appreciate how you consistently state the need for humility in your articles. And how this study promotes the need to be humble to what medicine can do or should do for a patient. Or at least promotes honesty with one self and the patient with what a therapy can do to help or harm a specific population.

“Translating trial results” is about the best job description there is for a practicing physician in the 21st century. He’s not the scientist, he’s not the trialist, and not the statistician. But this is what patients ask of him and trust him with and make life-and-death decisions based upon: this is the most noble endeavor of his day at work. Darn right humility is required, and dedication, study, sensitivity, discretion and intelligence. Tall order. The best doctors rise to it.