Dr. Satel is a bit of a regular here on Sensible Medicine. Today she returns to a topic that she wrote about in January 2023, changing our organ donation laws to increase organ availability.

Adam Cifu

What if we could solve the organ donor shortage with a simple tax credit? That is the idea behind the End Kidney Deaths Act (EKDA) (HR 9275).

The bill, advanced by the Coalition to Modify NOTA (NOTA stands for the National Organ Transplant Act passed in 1984) would provide a $50,000 refundable tax credit – $10,000 per year for five years – to any living donor who gave a kidney to the next person on the waiting list. The tax credit would be a 10-year pilot program.

The bill was introduced in the House of Representatives in August by representative Nicole Malliotakis (R-New York), Josh Harder (D-California), Don Bacon (R-Nebraska), and Joe Neguse (D-Colorado). Several more representatives have pledged to sign on, Modify NOTA says.

The coalition estimates that the measure will save 100,000 additional lives over 10 years. Conceding a “wide band of uncertainty,” a research team comprising two economists judge that number too optimistic, putting the estimate at closer 10,000 over 10 years, with a far bigger potential impact if the credit was extended to directed donors (those who give a kidney to a specific recipient).

In any event, the tax credit would almost certainly increase kidney donations by living donors above the current level of roughly 6,000 per year.

In addition to saving lives, the EKDA has a built-in “pay for” – as more patients received kidneys, the revenue loss from the tax credit would be more than offset by Medicare’s savings reaped from the fewer number of patients on dialysis. On average, Medicare spends almost $100,000 a year for every person on dialysis.

The idea of compensating donors is not new. It arose in 1983 during the drafting of the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA), spearheaded by Al Gore Jr. (D-Tennessee).

Initially, NOTA’s purpose was to create a national network of organ procurement agencies to collect and distribute organs from deceased donors. Under the pre-existing regional patchwork of agencies, there had never been enough organs to meet national demand.

Mr. Gore was rightly skeptical that even a new national system would meet demand, so he thought ahead. In July 1983, at one of several hearings to review the bill, he said, “if efforts to improve voluntary donation are unsuccessful consideration [would be given to the] provision of incentives, such as a voucher system or a tax credit to a donor’s estate.”

In September, 1983, as NOTA was being drafted, Gore learned that a Reston, Virginia physician, H. Barry Jacobs, was planning to recruit people from poor countries, fly them to the United States, and pay them for their kidneys, collecting a brokerage fee of $2,000 to $5,000 from patients or their insurers.

When Jacobs described his “business plan” to the committee — herding indigent people onto a plane to fly to a foreign operating room for a surgical procedure they barely understood — he triggered an outcry against the idea of wealthy people paying cash for organs while brokers profited.

The result was the insertion into NOTA of section 301, which makes it a crime to give or receive “valuable consideration” for an organ.

President Ronald Reagan signed NOTA into law 40 years ago this week saying “I have been encouraged by the response of the media and the public to this compassionate cause.”

Over one hundred thousand of needless deaths later, with 12 people on the transplant list dying each day for lack of a kidney, it has become clear that exclusive reliance on altruistic donations is a devastating failure.

I tell this story to make a bold claim: a tax credit for organ donors is consistent with NOTA’s original vision.

Understandably, when NOTA was adopted, lawmakers wanted to give altruism a chance — the main function of the act, after all, was to create a national network for voluntary organ procurement and distribution and maintain a list that had federal oversight. Section 301 was intended to prevent a traditional market system, in which wealthy recipients could buy kidneys, while others could not, and where immediate cash payments would be made to financially desperate and uninformed donors.

There is little reason to think that Mr. Gore and his fellow sponsors opposed the tax credit that he mentioned as a fallback option. A tax credit for donors who give a kidney to the next person on the wait list does not favor wealthy recipients over others.

And, disbursing the credit over a five-year period, along with informed-consent requirements, can ensure that desperate people don’t donate a kidney for an immediate financial payoff. (In an earlier article in Sensible Medicine, I reviewed the ethics of compensating living donors).

Over the years, as it became clear that an altruism-only policy carried unintended cruelties, members of Congress introduced bills to provide tax credits, or other benefits, to living and deceased organ donors (see Appendix A for legislative history). Notably, at a 1999 hearing, the American Society of Transplantation, the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and the National Kidney Foundation supported a bill that would have created a demonstration project that included financial benefits for the families of deceased organ donors.

Today, unfortunately, all three organizations refuse to support the EKDA. Financial incentives, they claim “pose serious unintended negative consequences to both donors and to public trust in organ donation.”

Four decades after NOTA’s enactment, it is time for Congress to adopt the End Kidney Deaths Act, which is compatible with the original spirit of NOTA. We should recognize, at long last, that altruism isn’t enough to save everyone who needs a kidney.

Sally Satel is a psychiatrist and senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a lecturer at Yale University School of Medicine. She is the recipient of two kidney transplants.

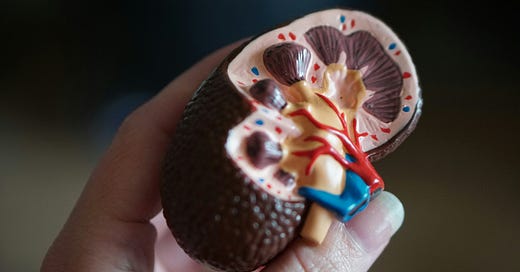

Photo By Robina Weermeijer

A truly grotesque idea that would amount in practice to harvesting organs from poor peoole for the benefit of rich peoole with good health insurance. Iran tried paid compensation and people who got injured by what is a major surgery were left with rage and regret. I recommend the outstanding work of Nancy Scheper Hughes on the ethics of organ trafficking: black market or legal, it is never just.

Horribly unethical in its own right- plenty of bioethics work has been done on this topic. Additionally, the cost analysis is obviously incomplete as it doesn’t account for direct or indirect costs of the organ donation to the donor or recipient.

But the biggest problem is that it would create a bizarre asymmetry or distortion in healthcare policy for preventing deaths from ESRD and only ESRD. That either just takes money away from all other medical care, including much more coat effective care, or starts a lobbying arms race where everyone gets a tax credit to incentivize whatever behavior pertains to ameliorating their favorite disease. As soon as you pay anyone for this or other organs, the altruistic organ market will disappear and more people will die waiting for organs than they do now.