When guidelines do not match the evidence--the story of beta-blockers after MI

This is a guest post from Drs. Mohammad Ruzieh and Andrew Foy regarding the changing evidence of beta-blockers after MI

We are pleased to share this well-argued piece regarding the changing evidence in post-MI care. Guidelines still recommend using beta-blockers. Ruzieh and Foy explain that the evidence underpinning this practice is outdated. And newer trials fail to confirm beta-blocker benefit.

This is a classic case of evidence requiring an expiration date. It’s also an example of guidelines being too slow to incorporate newer trials. JMM

Beta-blockers, are a class of medications that inhibit the effects of the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine on beta-adrenergic receptors. The discovery of beta-blockers marked a major advancement in medicine.

The concept of beta-adrenergic receptors emerged in the 1940s and 1950s, leading to the groundbreaking development of propranolol in 1962 by Scottish scientist Sir James Black. Over the following decades, numerous types of beta-blockers were developed, and they are among the most commonly used medications in medicine.

Beta-blockers slow the heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and decrease myocardial oxygen demand. They are widely used to manage various cardiovascular conditions, including hypertension, angina, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, myocardial infarction, and certain arrhythmias. They also have applications in non-cardiac conditions such as anxiety and essential tremor.

In this post we discuss how guidelines, not supported by recent evidence, may lead to overuse of beta-blockers in patients after myocardial infarction (MI).

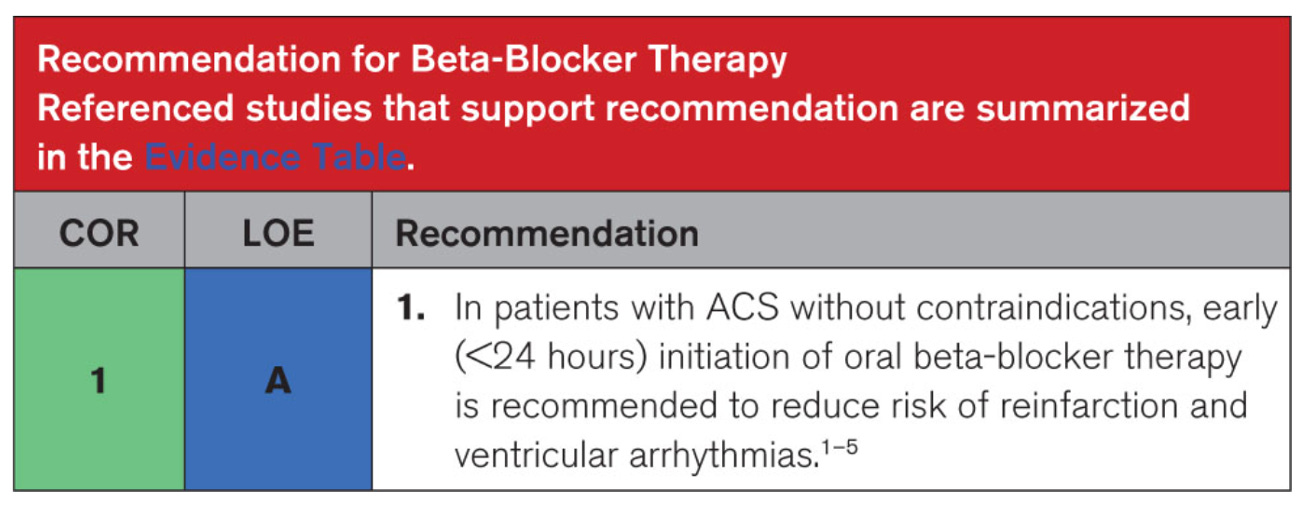

For instance, the most recent 2025 acute coronary syndrome guidelines provide a strong recommendation to use beta-blockers after myocardial infarction.

COR stands for Classification of Recommendations and LOE stands for Level of Evidence. COR 1 with LOE A is considered the highest level of recommendations and it tells clinicians to prescribe the medication or intervention to almost all patients who have no contraindications.

We question this recommendation.

In our Cardiology Trials substack, we reviewed the seminal trials of beta-blockers in patients with acute coronary syndrome, the same evidence the authors of the guidelines relied on.

Older trials showed improved outcomes with beta-blockers (BHAT and ISIS-1).

In BHAT, which was published in 1982, propranolol reduced death vs placebo over 2.1 years with a number needed to treatment (NNT) of approximately 33 patients (≈ 3% absolute risk reduction.)

In ISIS-1, which was published in 1986 had 16,027 patients, atenolol reduced vascular mortality vs placebo over 7 days and 1 year with a NNT of approximately 143 and 77, respectively.

Another important trial is COMMIT which was published in 2005 and had 45,852 patients. In COMMIT, metoprolol did not improve the composite outcome of death, reinfarction or cardiac arrest in patients with acute myocardial infarction. COMMIT, however, had substantial treatment effect heterogeneity. That is, in low risk stable patients, metoprolol led to a clinically small but statistically significant benefit, whereas, in higher-risk, unstable patients with heart failure, metoprolol increased death and cardiogenic shock.

A Different Time

BHAT and ISIS-1 were conducted in a vastly different era, and their results are not directly applicable to contemporary patients. At the time, reperfusion (thrombolytic or PCI) therapy had not become standard care for myocardial infarction; dual antiplatelet therapy was not in use; and statins were not part of routine management.

The lack of reperfusion therapy in MI led to serious heart muscle injury. Blockade of sympathetic overflow likely reduced MI complications. But now, rapid restoration of blood flow with stents has reduced the degree of muscle injury. MI now is quite different than MI of old. Thus, blockade of excess sympathetic outflow is surely less important now.

There is an even stronger reason not to apply beta-blocker evidence from these older trials to patients today.

A Modern Beta-Blocker Trial

The REDUCE-AMI trial, which was published in 2024, randomized 5,020 patients with acute MI and left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or more to beta-blockers or no beta-blockers. In this contemporary trial beta-blockers did not significantly reduce the composite outcome of death from any cause or new myocardial infarction, over 3.5 years follow up.

To appreciate the difference between patients in older trials and those in more recent studies, consider this: 10% of patients in the placebo arm of the BHAT trial died over 2.1 years of follow-up, whereas only 4.1% of patients in the control arm of the REDUCE-AMI trial died over a longer follow-up period of 3.5 years. Despite the extended follow-up, mortality was significantly lower in the more contemporary trial.

Evidence with an Expiration Date

Many treatments warrant re-evaluation over time, as their observed benefits may diminish or become obsolete with advancements in disease management. Beta-blocker use after myocardial infarction is a prime example.

While some patients, such as those with arrhythmias or persistent anginal symptoms, may still benefit from beta-blockers after myocardial infarction, we caution against assigning them the high level of recommendation found in the current guidelines.

Physicians, trainees, and advanced practice providers often rely on guideline recommendations to treat their patients, which will likely result in continued widespread use of beta-blockers in patients unlikely to benefit.

Although beta-blockers are inexpensive and generally well-tolerated, prescribing an additional medication still carries potential costs, whether financial or related to adverse effects. Even these small risks or costs become magnified at the population level (it’s estimated that over 800,000 Americans experience a heart attack a year).

I find it interesting that even a seminal cardiovascular trial that universally changed treatment for a common condition had an ARR of 3%. Meaning 97% of treated patients received NO benefit. And consider that most drugs we use with near universal consensus do not even reach that degree of benefit.

This is just one example of the folly of Guideline or Protocol or just plain Cookbook Medicine that has taken over the practice of medicine since the 1970s (?) and the rise of “evidence-based” medicine.

1. You don’t know that the correct or complete scientific data is included in the cookbook recipe.

2. The recipe, even if basically correct, doesn’t apply to the 5-10% of the population falling outside the standard curve.

3. While guidelines were initially constructed as a “floor” to keep poorly educated (or just dumb) doctors from practicing substandard care, they quickly became “ceilings” that gave insurance companies – led by Medicaid and Medicare – ammunition to deny coverage due to “over treatment” AND … allowed medical boards and hospital committees to prosecute doctors who did more than the guidelines indicated.

I’ve harped on this since at least the 1970s and now it’s pretty much enshrined in the EMR systems. 🤷