When Trials Find Implausible Results—The SCOT-HEART trial

I would love it if readers can help me explain how a diagnostic test can lead to major reductions in future MIs

Doctors seek therapies that reduce the chance of bad outcomes. When treating patients with suspected coronary disease, typical bad outcomes to prevent are myocardial infarction (MI) and death due to heart disease.

This usually requires drugs or interventions, such as urgent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stents during an acute MI. (PCI in stable disease does not reduce events.)

One of cardiology’s great mysteries came when a clinical trial called SCOT-HEART reported a 41% lower rate of MI or CV death with a CT scan. Not a drug. Not an intervention. An imaging test.

One group of patients with chest pain received standard stress testing; the other received standard stress testing plus a coronary CT scan (CCTA). The Edinburgh-based team presented their 5-year results in 2018, and their 10-year results last week. Both were positive.

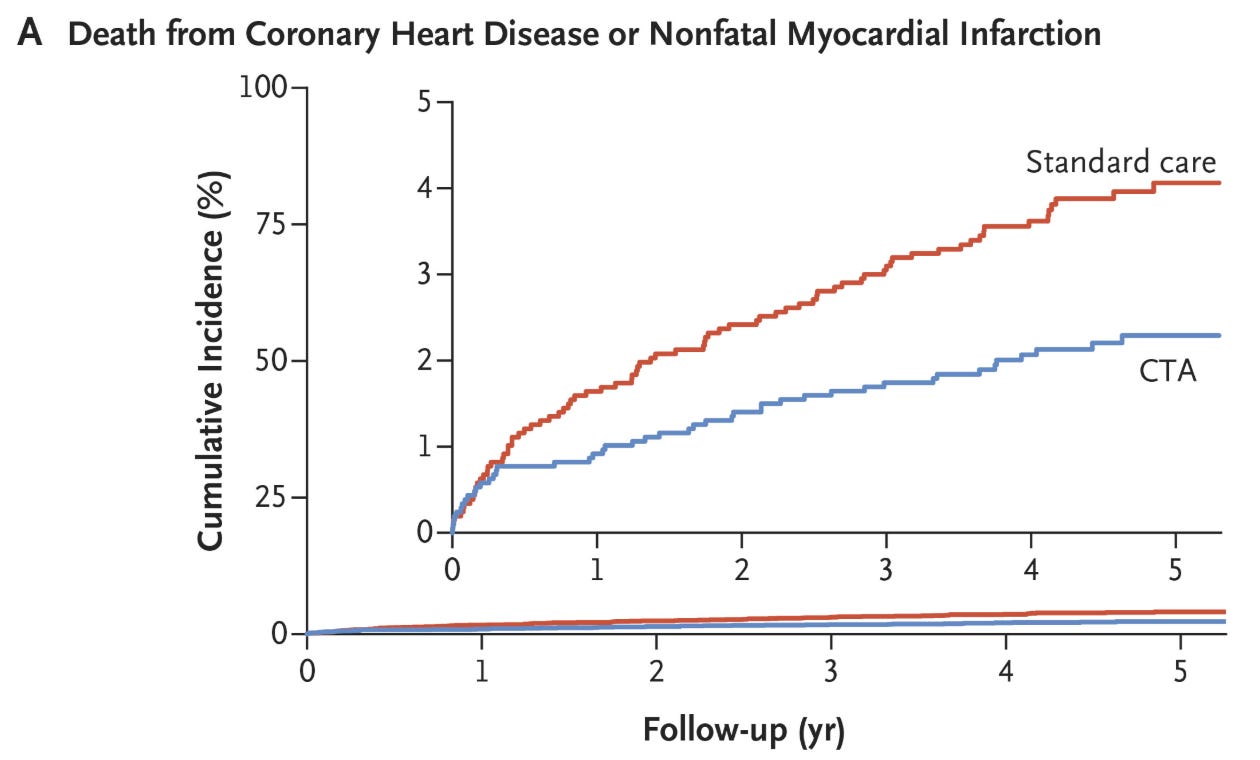

Here is the 5-year survival curves for the composite endpoint of CV death and MI:

How can a diagnostic test lead to this much benefit? That is the mystery.

Trial Description

SCOT-HEART was an open-label multicenter trial of more than 4000 patients with stable chest pain who were referred by primary care doctors to 12 outpatient cardiology clinics in Scotland. All patients had regular clinical evaluation, including exercise electrocardiography (ECG) if deemed appropriate, before being randomly assigned to either standard care or standard care plus CTA. Nearly 90% of both groups had ECG stress tests at baseline.

In the first publication from SCOT-HEART (2015), researchers reported that CTA clarified the diagnosis of coronary artery disease and led to changes in subsequent therapy—more preventive therapy and more coronary angiography. (This was the original primary endpoint). At 1.7 years of follow-up, death due to coronary heart disease (CHD) or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) was lower in the CTA arm (38% relative; 0.7% absolute risk reduction) but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

In the 5-year paper, in the NEJM, 81 (3.9%) patients had such an event vs 48 (2.3%) in the CTA arm. The hazard ratio was 0.59 (95% confidence interval, 0.41 - 0.84). Nonfatal MI accounted for almost all of the difference in event rates.

Two other important findings that informed the plausibility of the results. One was that there was no difference in rates of coronary angiography or stenting. There was however greater us of preventive meds, such as statins, aspirin and beta-blockers in the CCTA arm (19.4% vs 14.7%).

The authors concluded that CCTA should be the preferred testing strategy for patients with chest pain. In the discussion of the trial, the authors propose that CT scans better identify coronary disease (you can see it) and that led to more medical therapy, which then reduced outcomes.

Comments:

In 2018, I offered 5 reasons why I did not think a CT scan alone could shred MI rates by 41%.

The first issue was that preventive therapies are not good enough to reduce MI by that much. The difference in use of statins and aspirin were about 100 (of 2000 per group) patients. Statins and aspirin have at most a number needed to treat to prevent one MI of 50 (2% absolute risk reduction). This means only 2 of the 100 patients would have had an MI prevented based on higher use of meds. Another way to explain the implausibility of meds reducing MI by that much would be that it requires the NNT for statins and aspirin to be 3!

The authors also propose that knowledge of coronary artery disease could have induced favorable lifestyle changes that then led to fewer MIs. The problem with that is that it also occurred in another CCTA vs stress testing trial called PROMISE. But PROMISE found no difference in event rates despite a nearly 2-fold greater adoption of preventive meds and lifestyle interventions in the CCTA arm.

The second reason I doubt the SCOT-HEART findings is that it is an outlier. I co-authored a meta-analysis led by Andrew Foy in which multiple other trials found no difference in outcomes based on type of initial testing.

The third problem with SCOT-HEART was that it was open-label and MI events were tallied using coding data. Sanjay Kaul, an expert in trial appraisal, writing in JAMA-Cardiology, called this ascertainment bias.

Foreknowledge of normal coronary anatomy could potentially bias the investigator to not pursue diagnostic testing (biomarkers or electrocardiogram), thereby amplifying the difference in Mis. One would not expect this bias to be operational for mortality, which was not different between the 2 arms.

Another reason SCOT-HEART could have been positive is statistical noise. While the p-value for the difference in the 5-year results was quite low at 0.004, the difference in Mis was only 29. As stated above, judging MIs is tricky, because there is big difference between an enzyme-only MI vs an MI with ECG changes, symptoms and enzymes.

What’s more, as Kaul also notes, the composite outcome of MI and CV death was actually one of 22 secondary outcomes. The original primary end point of the trial was the proportion of patients who received a diagnosis of angina pectoris caused by coronary heart disease at 6 weeks, published in 2015.

Had the authors adjusted the p-value for multiple comparisons, using something called the Bonferroni adjustment, Kaul calculates it at a non-significant 0.08. This doesn’t mean the SCOT-HEART definitely was a false-positive. It means it was possible.

Final Conclusion

Please do look at SCOT-HEART yourself. I can’t explain how a diagnostic test that led to slightly more statin and aspirin use slashed MI by that much. No other trial showed it.

This is more than an academic exercise. SCOT-HEART helped launch CCTA as a favored way to evaluate patients with chest pain.

That might be OK in Scotland or other cost-constrained systems. But in the US, seeing CAD on a scan often leads to more downstream testing with angiography and stents and bypass surgery. (Of course, this is not the test’s fault; it’s the doctor’s fault).

While counter-intuitive, multiple trials find that none of that downstream revascularization leads to better outcomes over medical therapy. Yet, in the US (and Germany), procedures make hospitals and doctors lots of money.

I still favor functional stress testing for the evaluation of patients with chest pain.

Not saying that it did, but here's how it could decrease future MI by that much.

Let's say I have 2 fifty year old males in my primary care office. Both at intermediate risk of heart disease causing their stable angina. The one gets a stress test. It doesn't show anything that would benefit from heart catheterization (note I'm not sending patients for PCI in stable chest pain anyway). But the message he *unintentionally* gets is that he doesn't need a stent so he's fine. The next guy gets the stress test. Same thing. But then gets the CCTA. I note the plaque buildup in his arteries. He asks his friends if they ever had a CCTA. In 2014 it was way less common so no one has ever heard of it. He starts researching about it. He starts following all sorts of people and groups with a high calcium scores and plaque. And starts implementing all sorts of lifestyle changes we aren't able to measure. And so ends up switching out the daily cereal he has been eating for maybe sweet potatoes, carrots, meat, and some eggs. He starts cooking at home instead of buying takeout or going to a restaurant. He starts biking to work. And it's easy to venture a guess as to how that may be possible.

The part that is more interesting to me is the following: How many people suffered or died in the following 10 years? It's exactly the same. Did the higher statin use in the CT group predispose to more infections? Did they get thyroid disease from the substantial iodine infusion with the CT? Did they die of bleeding disease from aspirin? Did they get cancer? Did they end up on more PCSK9 inhibitors? Did they follow up with doctors more often, get more covid "vaccines" and die because of that? Or did he switch to a vegan diet to address his "high cholesterol" and ended up dying of a hip fracture? So all in all, I think we tend to focus on things we measure. It's hard to measure impacts on "whole person health" accurately.

Thank you for sharing the study! Overall it doesn't really change my bias towards doing or not doing the CT scans as a diagnostic but it changes the conversation a bit.

If patients knew the NNT values of these interventions, they might rethink the glorification of statins.