Who Do You Want at a Family Picnic?

If we want nice things, like functional primary care, we need to pay for them.

If you have practiced for more than a decade, you have experienced 2 to 3 cycles of “PCP renewal” through pilots, demos, advanced practice provider reinforcement (PA/NP), and occasional pay bumps. I refer you to the brilliant Lisa Rosenbaum and her current NEJM series on the state of primary care and the dire situation for PCPs. We have passed the point of no return, and AI will not be the bond that binds a siloed, chaotic system that optimists predict. Whatever is in store for primary care, the ideal model we envisioned a generation ago is not its future.

You may be aware that CMS recently released its 2026 Physician Fee Schedule update. Included in the package is a 2.5% downward efficiency adjustment for all providers, with primary care and behavioral health exempted. CMS has historically overvalued non-time-based procedural services, and the Agency’s decision to rebalance, however modestly, reflects an overdue correction. Primary care also received a much-needed boost with a series of add-on codes to help practitioners deliver management services for patients with chronic illnesses. However, if past is prologue, uptake of these codes will fall short of expectations. Nonetheless, CMS has made more than a token gesture, and the efficiency cut sends a signal to procedural-based specialties. As you might imagine, some doctors are not thrilled with the reduction, and many provider organizations have responded unfavorably.

Yet, if you asked a group of proceduralists whether primary care is the foundation for a successful health system, they would agree. I am also sure that if you explained the near-term budgetary shortfalls of the federal government—specifically, those related to Medicare and Social Security — they would also agree that no new money will be, or should be, allocated to support our system.

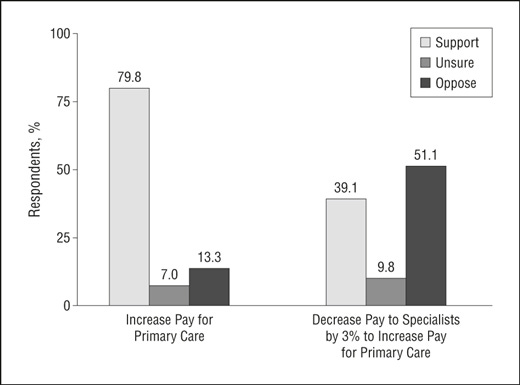

As the Affordable Care Act was readying for passage, a prescient study was published, asking physicians about their preferences for reforming doctor payment. No surprise, 80% of all docs supported boosting pay for generalists. However, only 40% of doctors would support a 3% cut in specialty salaries to fund such an endeavor (most generalists favor it).

Why?

As I alluded to above, the billions needed to fund primary care adequately are not forthcoming. In a nearly cost-neutral system imposed by statute, most doctors will not give up a portion of their income, any more than most people want to pay “a little more” in taxes, even if Uncle Sam promises it is for the greater good. Moreover, if you asked a hundred physicians of all stripes if society pays them what they are worth, a supermajority will say no, so the system comes second. Not a shock. We are self-interested. We are human.

If the true measure of physicians’ worth were the value they provided to the community they live in, primary care doctors would preside at the center of the system. Yet generalist pay never evolved to match the clinical “worthiness” associated with working in an OR suite, performing biopsies, anesthetizing, or ablating—tasks that the current market prizes.

Let’s look to history to explain how we arrived here. The divergence between specialty and primary care pay is less a carefully engineered plan than an accident of postwar timing and cultural momentum. After WWII, returning veterans entered training during a boom in hospital construction, specialty expansion, and cost-plus insurance models that rewarded procedures. Specialties accumulated prestige, influence, and lucrative revenue streams. Decades later, the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC)—dominated by specialty societies—codified these disparities into the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS). Well-funded professional groups defended them. And the public equated value with hourly revenue, reinforcing a cycle in which they see procedural work as more difficult, more venerated, and more deserving of compensation.

These forces produced a self-reinforcing system in which attempts at redistribution wilted. The provider healthcare pie is unlikely to grow beyond GDP plus a sliver. Yet one camp believes that expanding the pie will deliver more to primary care, while the other views the pie as fixed and wants a larger slice. We cannot reconcile those worldviews.

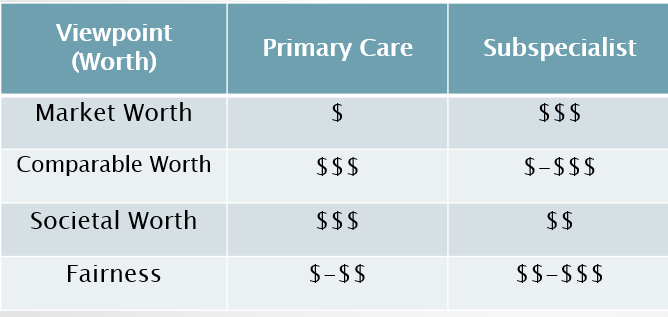

Consider four lenses of value or worth. Through Market Worth, RVUs dominate, however distorted that market may be, and procedure-driven subspecialists rise to the top. Under Comparable Worth, which assesses versatility of skills, primary care physicians often surpass subspecialists. Consider the breadth of skills over depth, and how the former, rather than the latter, augments the welfare gains of a population of individuals. For Societal Worth, imagine a family picnic with a strained back or a bout of gastroenteritis—families want a clinician who can handle almost anything, and be there when they need them. Think patient-centric.

But when we turn to Fairness, a utilitarian framework that incorporates key variables like training, practice stress, litigation exposure, cognitive load, and overhead, the lines blur. Fairness would require CMS to reassess its algorithms and reduce reimbursements for specific subspecialties. I will not name those specialties, but it is worth noting that geriatricians, palliative care doctors, and primary care practitioners are every bit as valuable, if not more beneficial than, what the RUC, RBRVS, and lobbying doctors have rendered over time. Cognitive load is the most overlooked, underacknowledged, and undercompensated attribute of any of the physician’s talent stack. Primary care docs have it in spades.

No one else will manage your musculoskeletal pain. No one else will fill out your disability form. No one else will respond to your portal question. No one will translate what your cardiologist said on Monday to your urologist on Wednesday. No one else will get to the bottom of your headaches. If we want nice things, we need to pay for them, and it’s going to require a bit of Peter paying Paul if we wish to reconsider value, fairness, and the root causes of how we developed our fractured system to make certain physicians whole. We can wait for primary care to collapse entirely. Or proceduralists can accept what they already know: their income depends on a primary care base they are watching crumble. It is not punishment, but an overdue step to preserve the safety valve and save the referral engine that undergirds their practices. The 2.5% efficiency adjustment isn’t the problem. It is a decade or two late (and probably too little).

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, is a hospitalist physician at NYU Langone. Opinions are his own.

As a family physician, I think you hit the nail on the head regarding the problem of excess cognitive load.

While being paid more for that work would be nice, I would much rather fix that problem. There’s too simply much to do in too little time.

It’s stressful, and worse, it makes you feel as if you’re never able to be the doctor your patients need you to be.

While I agree that reimbursement for cognitive services should be more on par with procedural services, as a “seasoned” FP who sees opening salaries for graduating residents of FP programs reaching 250K + , it’s difficult to claim “poverty “ or expect the public/lawmakers to have a great deal of empathy. The “fix” is to make reimbursement more market driven by giving patients more skin in the game.