Yet Another Broken Study Passes Peer and Editorial Review

I thought science was for finding truth and advancing a field

Last week I described a fatally flawed study that made it through the editorial process. The authors used a non-random comparison of two sets of patients and found an implausibly large reduction in mortality with a plug placed into the left atrial appendage of the heart.

A device placed into the left atrial appendage is there to reduce stroke and possibly reduce bleeding—because, in the best-case scenario, patients may be able to come off anticoagulants. (Though I argue in this video that these assumptions are not born out in the regulatory data.)

It turns out that this study wasn’t an outlier. I found another similar paper. I will show it for three reasons: a) learning is enhanced with repetition; b) the authors tried out a different argument to justify their biased finding; c) I will again speculate about the implications of flawed papers making it through peer review.

This post will be open to free subscribers, but if you appreciate our work, and the goals of this non-ad-supported project, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

This week, I found another similarly flawed study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

A Mayo clinic led team, along with Harlan Krumholz (Yale) and David Kent (Tufts), published a study comparing outcomes in patients who received either a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device or standard anticoagulation with the newer drugs—called NOACs.

The best way to compare outcomes would have been to randomize patients to each group. This would have had the effect of balancing known and unknown characteristics.

But that is not what they did. Instead, they used claims data from a US administrative database, from OptumLabs. They found ≈ 8400 patients who had LAAO and ≈ 554,000 patients who had NOAC therapy. Right there, you can see there is an imbalance.

The authors used statistical means to balance the comparison groups and write that, after the propensity matching (a way to balance non-random groups), the two groups were similar in 117 baseline characteristics. That sounds great, but the fatal flaw in this method, is that you can only balance for things in a spreadsheet. Doctors choose to use LAAO or NOAC based on many reasons, some of which are not in spreadsheets.

Their primary outcome of interest was a composite of stroke, bleeding, or death.

The picture shows the results:

After 1.5 years, there was no significant difference in the composite endpoint; stroke rates were similar in both groups; major bleeding was 22% higher in the device arm and pause for a second…overall mortality was 27% lower in the device arm.

The Kaplan-Meier plots of mortality show early separation with lower rates of death within 6 months. Last week, I said this was impossible. But this week, in this paper, it’s even more impossible.

Why?

Because we know that this device can only do two things: reduce stroke due to clots and reduce bleeding due to removal of anticoagulant drugs in the future.

These authors tell us that they found no reduction of stroke and higher bleeding in the device arm.

So, there is NO WAY the device could have caused this early and robust reduction in death.

The reason for the early separation of mortality curves is selection bias wherein doctors chose to do LAAO in healthier patients, and those factors led them to have lower death rates. (Unless there is some magical property of the plug unknown to mortal man.)

The Mayo Clinic authors are a little more careful in their concluding words than the authors I wrote about last week. The Mayo team does not say that we should use flawed data to discuss with patients. Instead, they say that their findings…

…suggests LAAO might be a reasonable option in select patients with atrial fibrillation.

They repeat this construction in the discussion:

The findings have important implications for clinical decision‐making. LAAO appears to be a reasonable option for AF stroke prevention…

The authors add a justifying reason for this spurious finding of lower death rates. They argue that this signal was also seen in the two clinical trials of Watchman vs Warfarin.

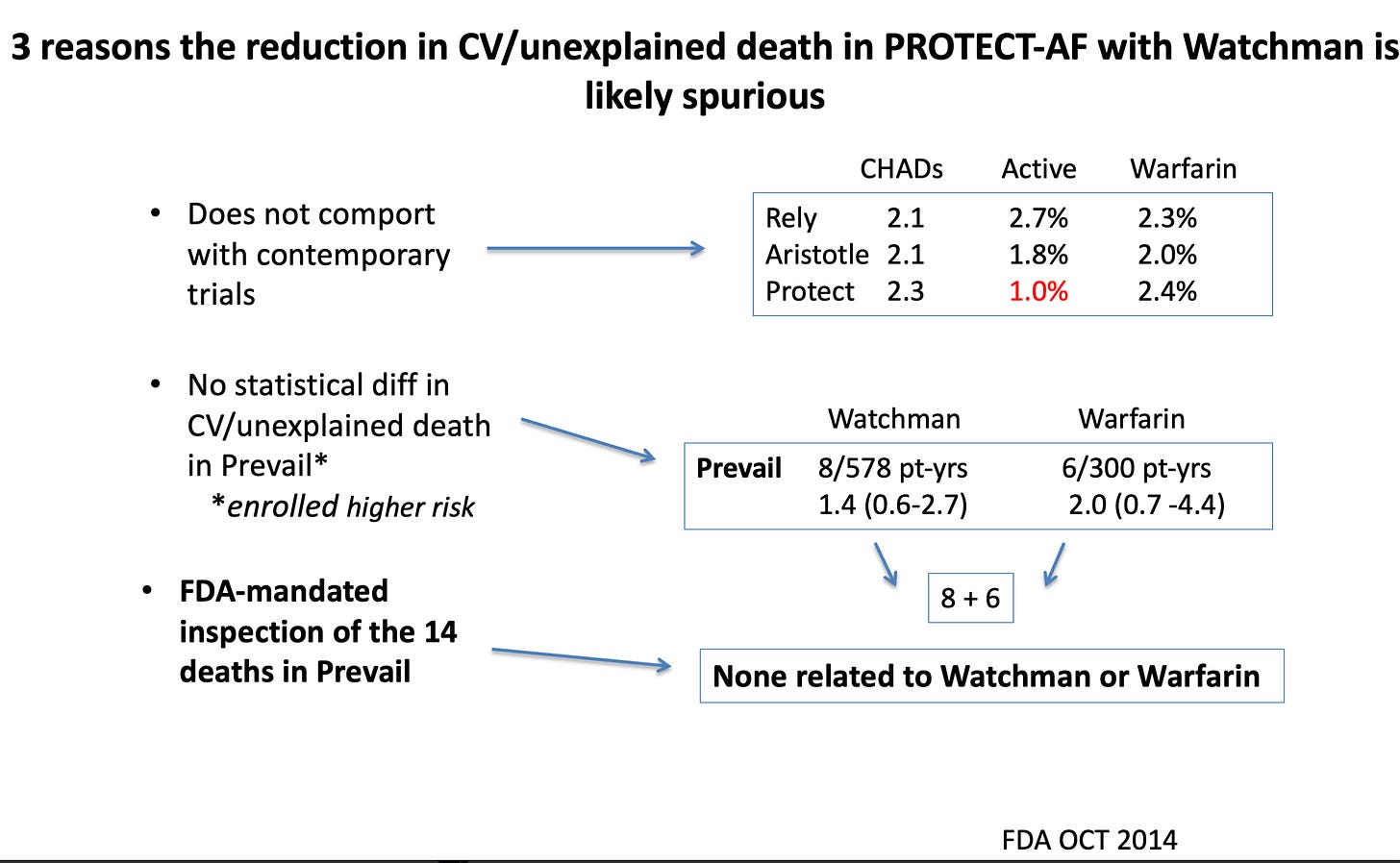

Which is true, but this too is likely to be spurious finding (noise rather than signal).

I showed a slide last week depicting why the cardiovascular death signal was spurious. Notably, the FDA inspected all deaths in one of the trials and found that not one death was due to either the anticoagulant drugs or device.

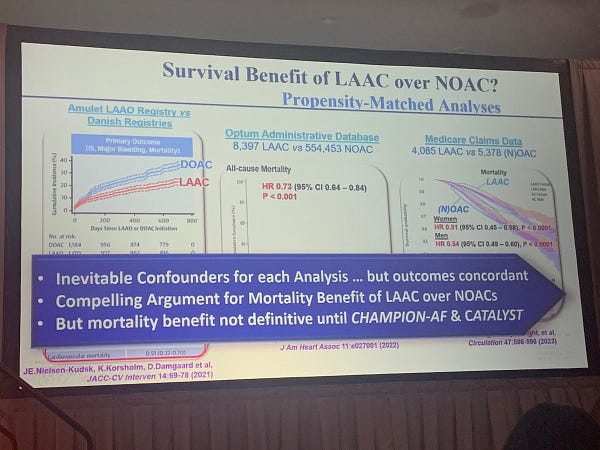

Another piece of evidence suggesting the mortality signal in the trials was noise is seen here.

Drug trials had tens of thousands of patients; device trials had a few hundred. You can easily see how it would be harder to separate noise from signal in small trials relative to big trials.

Now to some implications

Both of these implausible and flawed analyses have the imprimatur of major cardiac journals. This gives them credibility and doctors are noted for their rapturous uptake of data that purports benefits from procedures.

Evidence A is this slide which was shown at a recent AF conference I just attended.

Vivek Reddy, MD is one of the main trialists studying appendage closure. In his slide, he cites this study and the one I discussed last week. He adds caveats, but proposes that a reduction in stroke severity may be the reason why mortality decreases.

But that is surely wrong, as I showed last week, the LAAOS III randomized trial of surgical closure vs no closure, actually did show less stroke with closure, but it wasn’t enough to budge mortality rates.

That is because stroke is such a small contributor to causes of death in these patients.

Conclusion

The medical science apparatus seems broken. The authors are scientists. They know this is a flawed analysis. (They write about it in the limitations.) But those limitations don’t stop proponents from showing slides at conferences. It doesn’t stop the authors from writing that this may be a “reasonable” option for patients.

More than 50,000 LAAO procedures have been done in the US. It is awful that not one of these were done in a randomized controlled trial. If we had the wisdom to randomize even a portion of these 50,000 patients, we would know if this procedure works.

When I was a learner back at Indiana University, I had this notion that academic doctors were scientists interested in finding truth and making discoveries that advanced the field.

When I see studies like this from leading centers and leading academics, I wonder what the goals are? Surely these sorts of papers do nothing to move us closer to truth.

In fact, I would propose that by publishing flawed studies, we move further from truth.

It is sad. I really love cardiology, and I don’t want to become cynical.

The general problem: Data collected for other purposes is free and apparently irresistible. The false hope of "real world data" is biting us in the ... while delaying the launch of needed randomized trials.

Thank you for your fantastic explanations of this issue lately.

“they used claims data from a US administrative database, from OptumLabs.” This part stood out to me. Could it be as simple a matter as laziness? That is, in the old days, before fingertip access to huge online medical databases, you had to do the legwork of putting a study together, in which case if you’re putting in the effort might as well go the whole nine yards and do an RCT. But when you can get published in a major journal without leaving your desk, just running some opaque statistical tricks from someone else’s computer model on someone else’s database, it’s tempting to cut corners, no? Just a thought! I could be way off.