A Public Health Worker Looks Back at the Pandemic and How We Reacted to it

Like many of us, I’ll be thinking about the COVID pandemic for the rest of my life. I’ll think about those surreal first few months, the patients I cared for, the intricacies of the disease, and the progress we made in preventing and treating the illness. I expect to think most about the diverse ways that people dealt with the threat, risk, and uncertainty created by the virus.

Like half the world, I reread The Plague in the summer on 2020 and found it about 100 times more engrossing than I did when it was forced on me in high school. I have started to write about our disparate reactions to COVID myself and hope to continue.1

As much as possible, I have listened to and read about how people’s experiences shaped their views of the pandemic and affected how they are coming out on the other side. I have enjoyed reading the views of Dr. Matthew Brignall, someone who worked in public health during the pandemic, that he has shared on twitter. I reached out to him and asked if he would expand his tweets into a reflection for Sensible Medicine. I am thrilled he said yes.

Adam Cifu

My most memorable day of the public health pandemic response was a cold morning in late April 2020. The local health department, for which I worked, had just gotten a supply of test kits from FEMA and gained capacity to run them through our state public health lab. I led a testing team of nurses and administrators at a local memory care facility. The first patient I tested was behind a zipper door struggling to breathe. I remember her name – same as my grandmother’s. I remember the pictures on her nightstand and the sad sound she made when I did the nasopharyngeal swab. She died two days later, along with another several residents and staff from the facility. I admit to being terrified that day to be in the same room for the first time with the virus that was all over the news.

I joined the local public health response in March 2020, first via the Medical Reserve Corps, then as a part-time employee after federal emergency funding came through. I stayed on board until this month when the money ran out. During the last two and a half years, I had a front row seat for the public health response, and I feel that the narrative I read in many places today misses the big picture of what really occurred.

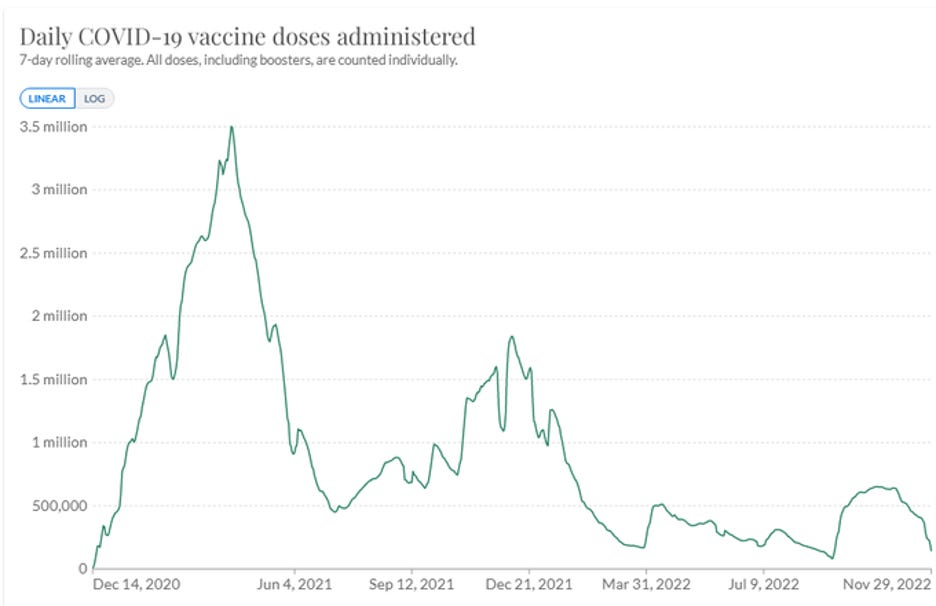

The most important thing to know about the pandemic – the thing I think the history books will feature twenty years from now – is that state and local health policies suppressed the spread of COVID-19 until we could develop an effective vaccine and get it into the arms of the most vulnerable people. The graph below is from the largest county in my state and demonstrates this clearly. During these same months, in areas that were more highly seeded with COVID, rates surpassed 5000 cases a day.

Caption: We kept cases low for nearly a year in the Seattle area

How did we do it? We did it by asking businesses to allow people to work from home, by asking bars and restaurants to close temporarily and then reopen with occupancy limits, by isolating and quarantining essential workers and care facilities when outbreaks occurred, by closing schools for nearly a year, and by using mask mandates in many settings.

Each of these steps was, and will continue to be, controversial. People will debate their efficacy long after I’m dead. That is fine, but I hope we can remember that these were good faith efforts by people doing their best to protect their communities.

The red arrow in the figure above marks the time where the infection rates started to rise. This happened about six weeks prior to vaccine approval. Why did it occur? At least in part, it occurred because leaders in many jurisdictions decided that motorcycle rallies, football games, political rallies, and the like were more important than keeping disease levels low. In a highly connected country, decisions by some increased the risk of all.

In the first six months of 2021, we performed a damn miracle. We stood up mass vaccine clinics in communities all over the country. In northern states, these were often located in freezing cold parking lots. We managed to get about 70% of the adult population vaccinated in four months. Public health teams and their partners took the vaccine to communities that are often invisible – immigrant groups, encampments, jails, adult family homes, nursing facilities – and got these people covered. We did it with a focus on equity and inclusion in a way that never would have happened in previous decades. Focusing on the minority of people who opted to not be vaccinated distracts us from the more important story of the historic and heroic effort. A study estimates this effort saved over 3 million lives and prevented over 18 million hospitalizations.

These past years were trying for me and my colleagues in public health. We have heard people screaming at us (literally screaming at us) that we weren’t doing enough and that we were doing too much. There was truth to both those complaints. Our pandemic policies caused a lot of suffering. We will be paying the IOUs from the response for decades. National debts mounted, businesses failed, kids fell behind, families were apart – this happened to people inside the response, too. The fissures that developed in the community, often along the same tired old red/blue divisions, will take years to heal. We all see the evidence for this in our clinics daily.

On the other side, many vulnerable people were furious that restrictions were lifted before we got close to manageable risk levels for them. It would have been impossible for our response to be perfect, but I know that we worked until we dropped trying. Everyone I talk to in the community can tell me a compelling story of their personal sacrifice, and not all of us have a clear understanding what it was for. Pundits play a very dangerous game when they weaponize this sentiment against public and private health systems.

I know that my colleagues and I aren’t going to get a parade. But my blood boils when I read pundits who act like our response was an overreach or, worse yet, a failure. The effort to rewrite (recent) history is well-funded and highly visible. I fear that it is working.

On December 7th, The Great Barrington Declaration twitter account tweeted the following quotation from an article in the Washington Examiner, "The lockdowns did not just cause an economic meltdown from which we will take years to recover. They also failed on their own terms. They killed more people than they saved." This is not only demonstrably false, but the magnitude of effect will not be known for years.

I am starting to see a troubling trend in the social media world. When critics of aspects of the public health response post, comments start showing up wishing harm on visible public health officials or complaining about how doctors can’t be trusted. My hope is that the people whose accounts cultivate these followings can work to turn down the volume, rather than continuing to ratchet it up.

From the last century, what do we really know about the efficacy of the public health response to the Spanish flu of 1918? Many people know about the different approach to school closings in Philadelphia and St. Louis. People know the anecdote about the Philadelphia war bonds rally (the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally of its day). We know there were fights over mask mandates and quarantine policies. We remember the heroic professionals who showed up to provide care, and have largely forgotten those who griped from the sidelines. But beyond that, we don’t know much about the daily decisions of local health officers and their outcomes on disease and economies. We know a little more about this recent pandemic, but there will never be close to certainty about any aspect of our response. I hope people will start speaking with less vitriol and lot more respect for those of us who rolled up our sleeves and did the hard and dangerous work.

Matthew Brignall, ND is a primary care provider in Washington State who worked as a member of the COVID-19 response team at his local health department. His duties included outbreak response, mass vaccination clinics, test-to-treat oversight, coordination of local services, and public and provider education. His opinions are his own, and do not represent any public health agency. He is the parent of a medically fragile adult daughter. If eligible, please support your local Medical Reserve Corps chapter.

Yes, I do know that The Plague can be read as an allegory. It made me happy to mention my name in the same paragraph that I mentioned Camus.

"I hope people will start speaking with less vitriol and lot more respect for those of us who rolled up our sleeves and did the hard and dangerous work."

I have nothing but respect for the individuals who rolled up their sleeves and did the hard and dangerous work OF TREATING PATIENTS. I have nothing but contempt, and yes, vitriol, for the individuals who shut down schools, shut down small businesses, coerced people into taking experimental medical products with no evidence of third-party benefit, manipulated data, condemned millions worldwide to poverty, deepened societal divisions by employing coercion, force, manipulation, and censorship, corrupted science, triggered a global mental health crisis, etc., etc. It is intellectually dishonest to conflate these two roles, even if some individuals performed both.

Treating patients is heroic. Authoritarianism is evil, even when imposed under the guise of "public health." It is terrifying to me that so many still haven't acknowledged the destructive hubris and arrogance of the past few years. Whatever happened to "do no harm?" Even if some of these measures "worked" (btw, they didn't. Sweden came a lot closer to getting these things right), they were harmful beyond measure. Absent sincere contrition, which is wholly absent from this article, vitriol is the appropriate response to these unrepentant authoritarians in lab coats.

Thank you for taking the time to write this account, I can tell you are writing sincerely. However, I do not think you have adequately grasped the full scope of what just happened, and as such I feel this retrospective falls short of accepting where this discussion must go if we have any hope of restoring faith in public health.

Let me just engage on this one point. You quote the Washington Examiner article saying:

"Lockdowns also failed on their own terms. They killed more people than they saved."

...and then reply:

"This is not only demonstrably false, but the magnitude of effect will not be known for years."

I'm afraid I must disagree. The only evidence you could possibly use to support your position would be computer projections of the number of lives which mRNA vaccination saved, which are not scientific evidence but merely hypotheses in need of empirical support. Even on their own internal terms, these studies look farcical (one that just came down the pipe overestimates COVID-19 mortality by an order of magnitude!) It is frankly shameful that the US media eats up these kinds of flaky puff pieces for Pfizer and Moderna. Touting such studies is certainly not going to restore faith in public health.

Incomplete though it might be, the best evidence we currently have is that, globally, lockdowns tragically did kill more people than they saved. This is just based on situations such as disruptions to medical care, screenings etc. Most of the deaths caused were not in the United States. If you restrict your view to the US alone, the more accurate position is your second clause "the magnitude of effect will not be known for years."

I would also encourage you to accept that what we're dealing with here isn't lockdowns, but a pernicious 'lockdown-until-vaccine' strategy. This was a drastic, untested health care intervention that was not only instituted in a great many wealthy countries, but those same countries pressured all other countries to align with this intervention - even though it was untested, and never entirely plausible.

If you want to see the worst harms of lockdown, look to places like Senegal, which lost its democracy to lockdowns, or look at the poverty inflicted on Asia, Africa, and South America by this untested and frankly reckless intervention plan. People in many of these countries were asked to starve to death to prevent transmission of a virus that posed essentially NO DANGER to them, because their population simply didn't include enough elderly people for SARS-CoV-2 to represent the public health crisis it was for wealthy countries like the United States with a vulnerable elderly population.

The best evidence I have been able to assemble suggests that the Great Barrington Declaration has been vindicated, just on the basis of excess data being posted end of 2022. It doesn't even matter whether these deaths are caused by lockdown complications or vaccine injury, it's all part of the same strategy. And regarding vaccine injuries, there is totally inadequate data because the CDC has failed completely in its moral obligations in this regard, but be sure to read this paper out of Germany which finally did the autopsies that the CDC refused to conduct:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00392-022-02129-5

We are dealing with potential negligent democide here. The unknown question is the scale of the deaths caused by these mRNA treatments.

In this context, which no doubt you consider preposterous, your concerns about lack of trust or the anger at public health officials lack a certain depth of appreciation for just how great a disaster was just inflicted on the world. As the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration tried to warn us, the proposed cure was worse than the disease. What we don't yet know is how much worse, and we still don't know how much of the harm was caused by lockdowns, and how much by these inadequately tested mRNA treatments. The fact that the British Medical Journal reported on a whistleblower demonstrating that Pfizer committed fraud in their trial data in November 2021 should have brought about an immediate pause to the vaccination programs and a requirement to disclose the source data - that this did not happen was nothing short of gross negligence.

https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n2635

For all these reasons, I advocate Truth and Reconciliation. Without it I do not believe we will ever reach any kind of shared understanding about what happened. There is so much that has already been revealed by research that has been declared 'forbidden knowledge' as far as mainstream media is concerned. It is hopeless to persist in this situation where we can have no common agreement about what just happened. It is pointless to lament that people no longer trust doctors without committing to a process of Truth and Reconciliation whereby people are allowed to tell the stories of the harms they suffered, and the truth might be heard about what was going on behind closed doors.

Again, I thank you for speaking from the heart. But your account of what just happened is at best a quarter of the story, and at least a quarter of what you believe is based on patently false interpretations of the available evidence, or indeed the negligent absence of evidence. If you truly wish to restore faith in doctors and public health, we urgently need Truth and Reconciliation. Saying 'we did our best' simply isn't enough to atone for the global disaster that was just inflicted upon the people of our planet.

In hope of a better future,

Dr Chris Bateman