Blind Patients, Blind Doctors

How screening incentives worsen primary care

With simple letter grades, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorses screening interventions for clinicians. But the organization’s influence goes far beyond its clinical reference tool. Regulators and insurers also refer to these guidelines to incentivize screening.

This sounds like a good idea. However, the effect size of most screening interventions is small. When screening becomes incentivized, more important interventions may become disincentivized.

Could this dynamic negate the fragile promise of screening? There is little to no evidence that boosting screening with incentives improves outcomes. Yet incentives drive primary care reimbursement.

I worry screening incentives may distort priorities and lead to harm. I recognized this possibility during my training at a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC).

A Case

PC was a 57-year-old woman living in West Chicago. We met at an FQHC where she had seen nine different primary care providers over 13 separate visits. Typically, she scheduled appointments were for osteoarthritis. Other times, she requested sublingual buprenorphine, which occasionally helped with heroin cessation. She also discussed cigarette use, dental pain, and gradual vision loss during previous visits.

Through the years, PC was offered a battery of tests. She was found to have high blood pressure, which led to a valsartan prescription. After a lipid panel, she was prescribed atorvastatin. A CMP revealed mild renal insufficiency and elevated blood glucose levels.

Without fail, screening tests were offered at every visit. PC was offered a colonoscopy twice, mammography four times, and a low-dose lung CT. She never completed any of the tests. She did have one normal pap smear result and low vitamin D levels twice. She was also screened for depression (13 times), alcohol abuse (5 times), food insecurity (once), and anxiety (once).

Reviewing her chart, I found no comments regarding her elevated blood sugar. Neither was an A1C or point-of-care blood sugar checked at follow-up appointments.

I noticed this because the reason for our visit was unlike the others:

Hospital follow-up, diabetic ketoacidosis, insulin titration

Senseless Medicine

It seemed PC’s physicians were blind to the patient in front of them. She was losing her vision for an unknown reason and bloodwork suggested a cause. An ophthalmology referral had been provided but was never pursued. Her pretest probability of diabetes was nearly 100%, yet no one connected the dots.

Instead, PC’s chart was littered with low-yield interventions. Well-designed RCTs have not proven that mood disorder or food insecurity screening improve mood disorders or food insecurity. Colonoscopy and mammogram screenings are unlikely to improve all-cause mortality.

Yet, these interventions were incentivized and pursued while obvious clinical signs were overlooked. I believe the arduous pursuit of quality metrics may have contributed to PC’s preventable hospitalization.

Primary Care’s Trojan Horse

FQHC employees are exceptionally altruistic. They turn down better salaries, more comfortable lifestyles, and association with prestigious institutions to provide primary care where it is needed most.

But good intentions only go so far. FQHCs are reimbursed at a flat rate regardless of visit complexity or duration. And primary care clinics everywhere struggle to navigate Medicare reimbursement rates that lag behind inflation.

As Americans become sicker and our healthcare more complex, FQHCs find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. They must take every measure to improve their finances. The pursuit of screening incentives has become necessary for survival.

At my FQHC, the following mantra was repeated by both administrators and PCPs:

“Not only does screening save lives, it also keeps the lights on.”

When every dollar counts, screening becomes a means of organizational survival.

How Is Screening Incentivized?

Insurance companies reimburse depression and anxiety screening. Additionally, the publication of screening rates adds reputational pressure to publicly funded clinics. But these incentives are only the beginning.

The screening chokehold on primary care largely stems from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). This influential non-profit manages the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). This list of quality metrics, typically aligned with USPSTF guidelines, is used by health plans to incentivize certain practices. HEDIS scores influence reimbursement through CMS Star ratings, Medicaid Pay-for-Performance programs, the Medicare Shared Savings Program, commercial Value-Based Care contracts, and Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Recognition. In short, the financial architecture of primary care makes bonuses and reimbursement rates contingent upon the uptake of screening.

Screening incentives are so numerous and consequential that primary care clinics sometimes refer directly to HEDIS while formulating organizational priorities.

Oddly, not all USPSTF guidelines become HEDIS quality metrics. An example is diabetes screening, which is USPSTF Grade B. But HEDIS does recommend diabetic retinopathy screening for those already diagnosed with diabetes.

In response to established incentives, my FQHC deployed universal depression screening. In an effort to accumulate normal blood pressure readings by the end of the year, they also encouraged PCPs to squeeze hypertensive patients into the clinic during the holiday season. Yet, routine diabetes screening was absent from every list of our FQHC’s priorities.

Clearly, the incentive system encourages gaming. But does it improve outcomes?

Burden of Proof

Same as medical interventions, incentives should be supported by clinical trials. Incentives cannot be assumed to decrease mortality or prevent hospitalizations.

A number of tradeoffs seem likely. Screening incentives may:

Decrease informed consent

Prioritize screening over patient complaints

Increase low-impact well-visits and marginalize sick care

Decrease a PCP’s flexibility in catering their practice to a community's needs

Produce ballooning administrative and medical costs

The burden of proof should be on policymakers to demonstrate that the benefits of screening incentives are worth the cost. To the best of my knowledge, this has never been done before.

Screening incentives should be justified by large, cluster-randomized controlled trials that measure all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality outcomes. Primary care clinics should be randomized to one of three arms:

Unchanged screening incentives

No screening obligations, but stable funding

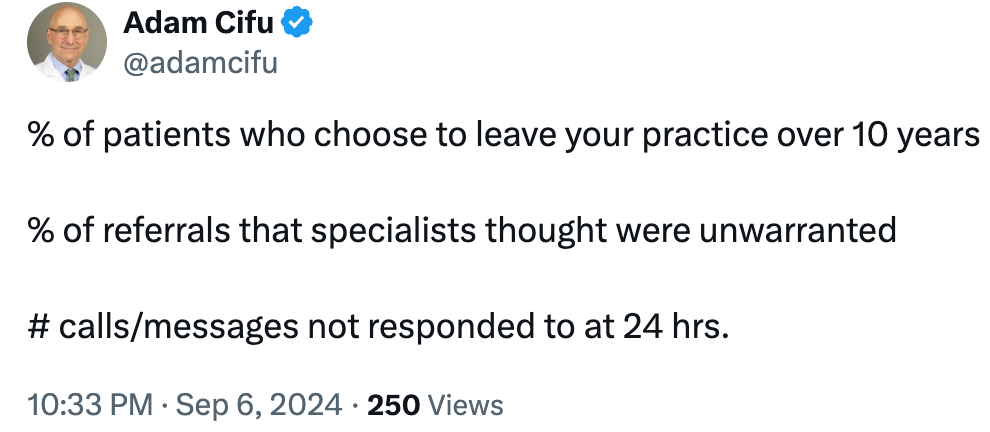

Alternative incentives to improve efficiency, continuity, and patient satisfaction. Consider Cifu’s Quality Measures:

If screening incentives cannot improve hard outcomes in clinical trials, they must be abandoned and replaced with a reimbursement structure optimized for simplicity and untethered clinical judgement.

Rethinking Primary Care

Screening incentives are intended to maximize uptake of proven preventive interventions. While this sounds like a good idea, the encroachment of mandated checklists on sound clinical reasoning could have dire consequences.

Taken too far, screening incentives could blind physicians to high-impact interventions when they arise. We risk creating a system where patients go blind from diabetic retinopathy before they receive a diabetes diagnosis. Could this extreme case be the tip of an iceberg of unrecognized harms?

The USPSTF suggests high-risk groups stand to benefit most from the expansion of screening guidelines. I fear the opposite could be true. As new guidelines become incentivized, primary care becomes increasingly scarce and impersonal for those who need it most.

My FQHC incentivizes HIV and hep C screening, which my mostly geriatric population is not interested in. I do not do well in this measure and could increase my take-home pay by wasting our time to convince them to do the screening instead of wasting our time with talk of grandchildren, dogs, and diabetes.

Although to be fair, I have seen no studies that show that asking patients about the people most important to them improves their outcomes either, or that it reduces doctor burnout, but I highly suspect it does both. I'd like to be involved in that study please.

As a retired FP who still precepts residents in a FQHC I have experienced the above screening conundrums. I frequently have to remind residents to concentrate on the Chief Complaint. Since most screening has minimal impact on All Cause Mortality honing in on the reason for visit seems a better use of the 20 minute visit.