Concierge Medicine Signals the Failure to Invest in Primary Care

At this point in my career, I know what I do well and what I do less well.1

I take pride in my accessibility. I am accessible in the sense that I am easy to reach – my patients can reach me by phone, text, email, MyChart, and can expect to speak to or see me quickly. I’ve also worked for decades to be accessible in the office. I try to be calm, collegial, and empathic. I know I have succeeded in being accessible because patients tell me they appreciate it. If they don’t tell me, they show me by reaching out when they haven’t heard from or haven’t been able to reach another doctor. If I let slip a hint of exasperation — “Why are you calling me about this, I didn’t order this test?” — I’ll hear, “I know this is not your responsibility, but I know I can always get in touch with you.

All that said, every day I put off calling patients. I delay returning a few calls or releasing test results. I do this not because there are enough hours in the day. I do it because I just don’t have it in me. There are times when I need to let a result sit so I can reflect on it. There are times I can’t face one more conversation. There are times I’ve just had enough of clinical practice and need to spend some work hours writing a talk, reading a journal, or writing a Sensible Medicine post. There is also the truth that one can never really empty the Epic in-basket — the half-life of the “No messages. Nice Job!” message is measured in minutes.

Why do I reach this point of communication fatigue? Why is there a time, almost every day, when I can’t finish all my work? I am a good obsessive who got where I am because of my ability to postpone joy and sit on my butt and work.

Communication fatigue exists because the job is just too hard. Now, I recognize I do not have the hardest job in the world. I don’t even have the hardest job in medicine, not by a long shot. I don’t even have the hardest job in medicine in my family. Other doctors take care of sicker patients, deal with more death, or perform procedures that I can’t imagine doing. I’ve watched The Pitt. What stretches me to the breaking point is the volume of the need. There are patients of mine who need to be cared for. There are patients who need updates, reassurance, or explanations. People need refills, referrals, and prior authorizations. There are requests for earlier or more convenient appointments, as well as to join my already full and overwhelming practice.

That I am not up to the task is bad for me. Fortunately, I have learned what I need to do to protect myself, to maintain my happiness with my work, my career, and my life. Still, I feel bad leaving things undone. And, on days when I feel like I have nothing left, and something arises that needs to be done, I often run close to my edge.

That I am not up to the task is bad for my patients. I do not think that my procrastination does any real harm, but people need to wait for results, or wait to have their questions answered, or to have visits arranged. I am sure this leaves them less than perfectly satisfied.

What is behind all this? For decades, we have not invested enough in primary care. We don’t have enough primary care doctors, so the ones we do have are asked to care for too many patients. Our primary care doctors don’t have the resources to do their jobs efficiently.

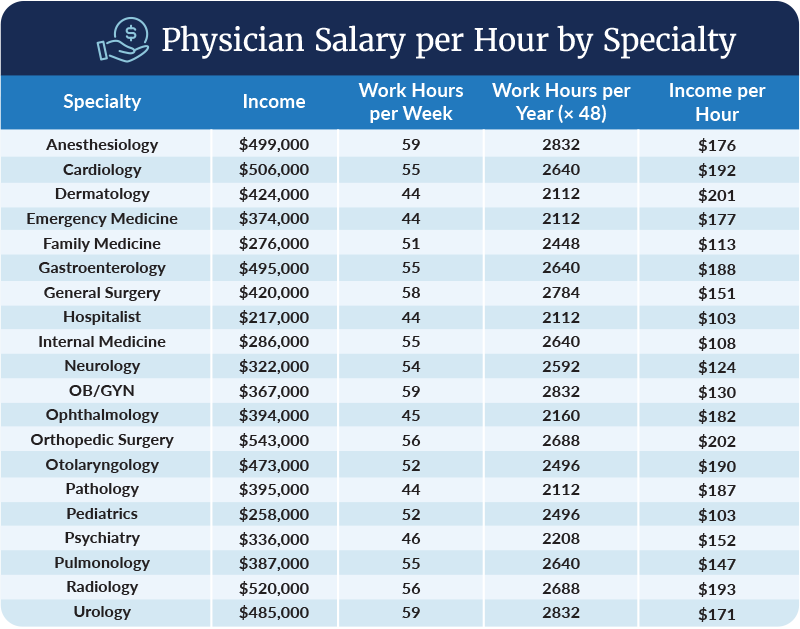

I do not think this is about low pay leading people to avoid the field. Yes, primary care doctors do make less than most other doctors:

Source: White Coat Investor

But, come on, we are not hurting. The mean income for an internist in 2025 is 286,000. But the work is just too hard. It is hard to recruit students and residents into the field when they see even successful primary care doctors, the ones who love their work, the true evangelists, running close to burnout.

The proof that the work is too hard and that patients are paying the price is demonstrated by the exodus to concierge medicine and similar practice models. Our failure to invest in primary care created a population of doctors unhappy with their work, feeling like they were working too hard while failing to provide the care they wanted to. Patients are unsatisfied with doctors who are too busy to provide the time and attention that they expect and desire.

There was a time when I bemoaned these practices. I no longer do. Although some concierge practices market themselves by hawking unproven tests or therapies or selling modern-day snake oil, many of these practices, including most that label themselves as direct primary care, offer attentive, personalized medicine at a scale and pace that is good for patients and doctors. One of the beauties of a free market is that when a need arises, people are incentivized to fill it. Direct primary care exists because 21st-century American primary care breeds the need among patients and doctors.

There is some harm in these practices. The concierge model does lend itself to over-testing. The resulting overdiagnosis increases demand on our shared-risk systems (private health insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid). Both direct primary care and concierge medicine take doctors out of the public pool, theoretically leaving the doctors left behind even busier. I expect this effect is very small, and the doctors in these new model practices certainly cannot be faulted for the failures of traditional primary care. They are, in fact, setting up systems more desirable to both doctors and patients.

I am optimistic about the future, only because the solutions seem relatively simple. Our direct primary care colleagues are showing us how to design practices that work for doctors and patients. We need to invest in scaling these designs to everyone, not just those who can afford it.

I am also optimistic because I know how truly rewarding and satisfying it is to practice primary care.

I have tried to be honest in this space about all the things I struggle with.

One of the things that concierge medicine does, is enable the physician to limit the number of patients in their practice. It enables them to practice the way that they want to. They don't feel like they are seeing patients on a conveyor belt. They run their own practice instead of being controlled by a corporation. I don't blame them one little bit.

Well said. At one point I considered converting my practice to concierge but I considered it to be selling out. I no longer view those who leave for concierge to be sellouts. I was sad when a colleague of mine left for concierge recently but understood that it was an indictment of the current state of primary care and not a reflection of her values. Concierge medicine is an indictment of the existing system but at the same time it is an affirmation of how much people who can afford it value and are willing to pay for access to a long term trusting relationship .with a PCP